An Interview with John A. Williams

John A. Williams Interviewed by Dennis A. Williams

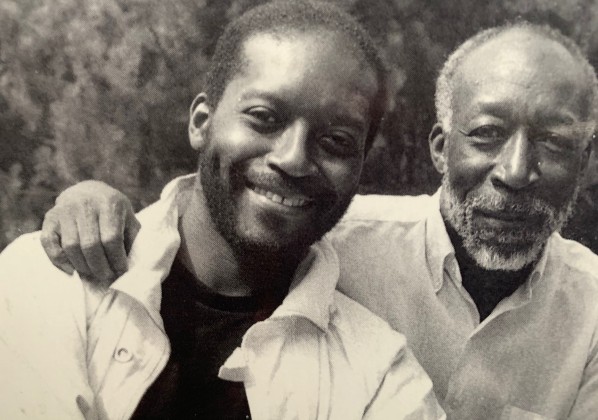

John A. Williams (right) and Dennis A. Williams

Originally published in FORKROADS, A Journal of Ethnic-American Literature, Winter 1995

For me, at first, he was always, above all, a writer, a romantic figure. A world traveler, Greenwich Village bohemian, jazz aficiconado, peace activist, outdoorsman and lover of art. And an impossibly well-read man who could turn the most casual conversation into a teaching moment with references to obscure philosophers and historians. That he was also my father only complicated matters. It took many years—and reading between the lines of many novels—to know him as well as the fun-loving, rambunctious kid from my own Syracuse, New York, neighborhood: an easy-going, would-be jock with whom I could watch a Super Bowl, fall out laughing to Richard Pryor and, in time, get drunk.

Those split images began to come together as I grew to adulthood and—both because of and in spite of him—ventured to become a writer myself. His legacy, however, remains daunting and secure from filial challenge: 13 novels, eight nonfiction books, ten edited or co-edited volumes including two literature texts, and a forty-year history of publishing short fiction and poetry. The Man Who Cried I Am, published in 1967, cemented his public reputation as a compelling and uncompromising chronicler of politics, race and the human heart. Yet his wide-ranging interests have always eluded easy categorization.

Those split images began to come together as I grew to adulthood and—both because of and in spite of him—ventured to become a writer myself. His legacy, however, remains daunting and secure from filial challenge: 13 novels, eight nonfiction books, ten edited or co-edited volumes including two literature texts, and a forty-year history of publishing short fiction and poetry. The Man Who Cried I Am, published in 1967, cemented his public reputation as a compelling and uncompromising chronicler of politics, race and the human heart. Yet his wide-ranging interests have always eluded easy categorization.

It is to his credit and my enduring pride that one of his nonfiction books was also the first to bear my name, If I Stop I’ll Die: The Comedy and Tragedy of Richard Pryor, which we wrote together. at his suggestion His invitation to me to conduct this interview was but the latest expression of a generosity that has evolved from paternal to collegial.

We spoke in the spare living room and on the perfect porch of his Upstate New York hideaway, where he had taught my younger brother , as well as my older brother’s children and my own, to shoot, play and understand that they have a special place in the world. It is the place where he is most at home, where all the parts of him come together, from the booklined writer’s studio to the fishing dock; where both the collection of jazz records and the telescope aimed at the clear, rural sky can transport his spirit; where his mother’s ashes are buried. Because it was an official, taped interview, the occasion seemed oddly formal. But because it was also a synopsis of forty years of such conversations, it was entirely natural. He doesn’t change: the Syracuse kid, the poet-philosopher, the compulsive teacher, student, parent and bop-cool hang-out buddy are all alive and well in John A. Williams.

Dennis: When did you know for sure that you could do this, that you could be a writer?

John: I never know for sure.

D: You’re still not sure?

J: I’m still not sure.

D: When were your sure enough to commit yourself to it?

J: It wasn’t a question of commitment, Dennis. It was a question of doing something that I thought I might possibly be able to do in order to maintain sanity. I know Baldwin has said that and I have said that before myself, but in a world which really, given certain situations, doesn’t give a shit whether you exist or not, it is very important that you yourself create yourself and you do that by—or at least I did it I think—by writing.

D: You recently completed your 13th novel, Colleagues, which you said would be your last talk about it a little bit.

J: Well it’s set in a university and it’s told from the point of view of an African-American professor. There are a lot of African Americans in the book in places where I don’t’ think you very often associate them except for the athletes—and there are plenty of athletes. I use custodial staff. I try to pit a couple of ethnic groups together in a struggle for power of the campus. I set us a plot with the KKK which is more a sense of forboding than an actuality, and that’s about it. I enjoyed doing the part about the athletics, I enjoyed doing the departmental conflicts. Anyway it’s something I wanted to do and it’s done so now we’ll see what happens to it.

D: Why is that your last novel?

J: Because I don’t see fiction doing anything, at least not the way I think fiction should do things. And it’s true that when I begin a book it’s usually something that I want to say. I don’t have a fixed audience. I hope the audience like metal scraps to a magnet become attracted to it, but I am just really disgusted with publishing in general, the quality of editors or lack of quality of editors, the whole who-struck-john that makes as far as I’m concerned writing fiction not ANYTHING I want to do anymore.

I’ve always looked at fiction as being a corrective force or a force for some kind of truth and ah I feel now that that’s a view that is not popular.

D: You have another one the one before that, number 12, Clifford’s Blues?

J: Trio: Clifford’s Blues, yeah. People of the University of Mississippi seem to want to do it. We have to talk some more about various things, but it’s amazing what’s happened to that book.

D: What kind of reactions have you gotten?

J: I think i must have gotten 30-40 reactions. They were not different; they were all pretty much the same, and as I may have told you I came away from those with the clear impression that I was not supposed to be doing this kind of book.

D: What kind of book is it?

J: It’s a novel centered on the diary of a black musician in Dachau from 1933-1945. His diary’s discovered in Germany by a black couple there on vacation who get it to the only black writer they know. The trio is comprised essentially of Clifford, who is the musician, and Jay, the writer and Bounce, who is the guy who discovers the diary.

D: Do you feel you have left any stories untold?

J: Yeah, probably a novel about aliens who actually turn out to be black people from some where (laughter) manipulating these little people everybody sees.

D: Good idea, I’ll do that one. How would you evaluate your career as a novelist?

J: I don’t think I’d even try.

D: Okay, what would you consider your best book?

J: I like to think Click! Song is the best book. I think I did things with structure better than I did with Sissie or The Man Who Cried I Am, and it seemed to work best. I think I got into a writer’s life pretty good, but yet that was not the key element of the novel. What was was the marriage of Cato [Caldwell Douglas, the protagonist] and Alice, and secondarily the rivalry between Paul and Cato, which in a sense is like another marriage but the secondary one in a sense very painful for me because it reflected an experience I had with a very dear friend, Dennis Lynds, for whom you are named. Who just sort of stopped maintaining contact because he thought I was getting more applause than he was as a writer, which was not necessarily true. But that sort of led me to thinking, and I never wanted to think this, that he was like so many other white people I have known who if they think you’re getting ahead of them the play ends. So that aspect of it was kind of painful, but that’s the way it is. And some things I wanted to say about kids and the world in general.

I don’t know that I’m that unhappy with any book. I may be unhappy with the reception a book got, but I’ve said what I wanted to say in every book. Few people have heard of The Berhama Account , but I thought that was my funny book along with Mothersill and the Foxes, which of course was a bit deeper than Berhama.

I learned early on you just can’t do a book and sit around waiting for good things to happen to it. The sense is, fuck it, let’s get on to the next one. And that’s pretty much the way I’ve been working.

D: Is that why you won’t read a review until a year after the book has been published?

J: That’s right, yeah.

D: Can you talk a little bit about your approach to work? I’ve always thought of you as a lunch-pail kind of writer. As far as I know you have never not been working. You’ve always got something going on, you’ve always got a project. One foot after the other. Why?

J: It’s become kind of a way of life, and I’m not sure it’s not also seeking shelter from storms, that could be a part of if. But I write every day practically. For me it’s like putting on my pants. And if I’m not writing I’m taking notes while watching TV or something else, but my mind is always somewhere in the production of something or finishing something and sometimes starting something.

D: The Joplin family appears in several of your books, the first time in Sissie, I believe, and right up through this last one, Colleagues. What is the meaning for you of that fictional family?

J: Longevity, and some depiction of family ties through the generations and what happens to them. And in the case of the Joplins not much spectacular ever happens to them, they’re just sort of grinding it out generation by generation, and I like to think that’s pretty much what African American families do, for better or for worse. And of course I guess it’s not so amazing but I don’t know of any reviewer who’s picked up this family and followed the continuity through all of these books. But then critics I tend to put in the same category as editors, and maybe I’m spoiled. Because when I began I met some really fine editors and critics as well. My sense is that they are really not out there now.

D: I’ll say this so you don’t have to. I never thought your work has gotten the respect that it deserves. Any ideas why not?

J: Yeah, I’ve got a few.

D: I thought you would.

J: Well, I don’t want to belabor a lot of dead horses here, but I think beginning with this Night Song business and the American Academy , the National Institute of Arts and Letters — that thing has really been like a cloud over my entire career. [Dad: can you fill in some details here—maybe a footnaote?] On the other hand I’ve done my share to make that possible, having had this run-in with people at the [New York] Times. Everybody wants you to kiss their ass and I’m not going to do that. And at Newsweek I think the only review I got was The Man Who Cried I Am . And after I ran that essay on how they wanted me to be books editor and then they didn’t want me to be a books editor and naming names… there are people out there who have simply not forgotten. There is an editor at one of the literary publishing magazines who told me about four years ago that he thought it was a shame what they were doing to me. When I finally got around to asking him who were the "they "he just wouldn’t respond. But that’s life, you know. If you don’t piss people off as far as I’m concerned you’re not doing anything.

D: What do you most like and dislike about being a writer?

J: Oh, I most like language and ideas and weaving cloth from them as well as from experiences. I can’t say i dislike anything about it, even now. I like the idea of being thought of as a writer, if not your screaming famous writer .

D: What would you say in terms of a literary career has been your biggest thrill, the high point?

J: Literary career? Well, I never looked at life that way. But I can tell you I did a play, The Last Flight From Ambo Ber, and it was read in a little theater in Cambridge. And I thought that was the most exciting thing that has happened to me, to hear these words coming off the stage. I found that pretty astounding. That was incredible.

D: Was there a low point?

J: Low point, yeah I had a low point before I really got into writing, but it didn’t have anything to do with writing. It had to do with what was going on in my personal life. And I think the writing helped me get out, get over that .

D: Poetry is your first love.

J: It is.

D: Why?

J: I don’t know—because iIve never been good at math or algebra or any of those things, but poetry for me comes closest to becoming those things in terms of rhythms and cadences and certain images. And I like the compression of ideas that you have to deal with in poetry, which is not to say that all of my poems are that short—I’ve got some that go 3 or 4 pages long. I’ve got a poem called "The Journeys" and that’s about the family, and that could be a whole novel and maybe it has been two or three novels but this is about 3 or 4 pages.

D: You’ve also done obviously a lot of nonfiction. You mentioned the play. Any screenwriting?

J: I did a bad screenplay for Clarence Avant for [my novel] Sons of Darkness, Sons of Light. Nothing ever happened to that, but the world is so filled with shits that as soon as Clarence’s option was over people started calling me up in the middle of the night from Hollywood and I would say to them talk to Clarence because Clarence had been most decent with me. So for about two years after his option was over and people would call, I’d say you talk to Clarence, but I guess they didn’t want to talk to Clarence .

I’ve started dabbling with a new screenplay based on The Man Who Cried I Am since I saw you last. Julian Flowers, who won an Emmy for a documentary on Eleanor Roosevelt, flew east and we talked last week. He gave me the names of some writers who are interested in doing it. He was naming all these people who as far as I was concerned were like the kiss of death, artistically speaking, so finally i said why don’t I take a crack at it. And of course it had been a set-up all along; that’s exactly what he wanted. And he said, well, you will protect your story if you do. And so that ’s where we left it and we will be talking .

D: What different kinds of satisfactions do you get from the different kinds of writing?

J: Each has its own kind of discipline but if you asked me to name what that kind of discipline is I couldn’t . But I know if you’re doing a screenplay you’re seeing more than telling as you would do in a novel. A play has its own overtones and shadows, strong and weak characters playing against each other and poetry has its subtleties and its brashness, coolness, hotness whatever.

D: What about straightforward non fiction prose as opposed to fiction. Obviously they are different, but are you aware of any particular difference in your approach?

J: Yes. Some of the things I want to say and share with people. And very often when I approach non fiction it’s with a club in each hand, and I know that’s not always good but there you are .

D: What would you say to Johnnie Williams if you had him in class now? As you were when you took the class with Coachman, the professor who let you know that maybe this was something you could do. If you had somebody who was like you were then in your class now what would you tell him? Would you encourage you to try to become a writer ?

J: I don’t think I would, and as a matter of fact these graduate students I had, I would encourage their writing and at the same time I would tell them how damn difficult it is. That doesn’t deter people who want to write, but it’s only fair to tell them what they are going to face.

D: What do you think about MFA programs?

J: They are better than the Ph.D. programs, but I’m wondering now out of all the people now attending MFA programs, how many are actually going to end up being writers? I guess, oh, about 20 years ago you could count the number of people who did well coming out of those programs on two hands. I don’t know what the figures are now, but it’s getting very, very crowded. I tend to feel that the old school is somehow best and closer to where a writer should be. That is, you work all day, you come home and you write at night. You’re out seeing people, undergoing different experiences. You’re not in the classroom dealing with theories and competing with other writers. You’re just out there traveling if you can and seeing what’s what in the world, seeing how London matches up with Boston and what have you, and that may be old-fashioned, but I think given the way writing goes, that’s what most writers have done until a comparatively recent time.

D: You’ve had several "trifling" encounters over the years.

J: It’s very dismaying. I get a number of requests from black people doing magazines or books and stuff and they ask for things and I’ll send it to them. It’s more of a case of responsibility rather than money; usually there is not any money involved or at maxium very little. But I find that the idea of being courteous in this kind of relationship doesn’t seem to happen with people. Here are the poems you asked for, okay, it’s been nine weeks, are you going to run these poems or not because I’d like to send them somewhere else. No answer. Just completely, who gives a shit? With certain editors who are putting anthologies together essentially the same thing: they won’t tell you that you’ve been dropped out of the table of contents. You find out inadvertenly and call for an explanation and all they got to give you is some trifling nonsense.

"Trifling" is a term meant to define irresponsibility, incivility, and that’s the cheapest kind of human intercourse you can have, to be courteous. It doesn’t cost much, maybe 32 cents for a stamp. I find increasingly that that seems to be lost, not only with numbers of young black people in publishing but in publishing in general.

D: Why is it lost?

J: I don’t know. Maybe people are too busy to be courtious or civil . Maybe they really don’t give a damn about you unless they see that through you they can make a bundle very quickly.

D: What do you enjoy reading now?

J: I’m reading a hell of a lot more nonfiction than fiction. I’d like to finish reading all of Leo Campanto’s[?] work . He’s my kind of novelist, historic sardonic, subtle whatever. I read —absalon by alexis Pate, I thought that was a very fine book, and these books by this young Williams.

D: Is there any author or works that were particularly influential in terms of your own work?

J: Probably Wright. I can’t nail that down because I read so damn much and Wright, when I was going to school, was not one of the authors you would automatically get to. You were pretty much on your own. I really can’t say.

D: Right now what would you say is the best novel you’ve ever read?

J: I’d have to give you two. For Reasons Of State by Aumauyo Carpontier [?] and Bound to Violence by [?]Logan. I reviewed it for the Times years ago. I think there is some controversy about the book as to whether he wrote it or not, and I don’t think that was resolved. But that was the grandfather of all books, all novels. It dealt with the experience of being educated in France and returning to Africa, and I must have read about a dozen of those books since then. It was a great book.

D: I thought you might have said Under The Volcano.

J: That was my teaching book. I learned a great deal from it in terms of what you can do with time. How you can confine it, shift it, weave it back on itself, whatever. I guess it’s the same thing painters do when they have a canvas. How am I going to tell this great big damn story on this piece of canvas?

D: You first wanted to be a trumpet player.

J: Yeah, actually I first wanted to be a great athlete and then a trumpet player when I discovered how well I could play the bugle. There were no programs at Dunbar Center where you could rent musical instruments or anything. You could go to a music shop and rent them but that was far too expensive, so I just didn’t pursue it.

D: Are there other people that you particularly admire in other creative arts, other than writing, such as musicians , painters?

J: Yeah, I’ve always liked Charlie White, who has been dead for quite a while now . His art always struck me as my non fiction writing, clubs in both hands. And Tom Feelings. He has a new book coming out, it’s called The Middle Passage: White Ships, Black Cargo, and it’s fantastic. It’s all done in black and white and greys and suggestive swirls, yet it’s a very graphic, tough book . Feelings is very good and Romare [Bearden] I’ve always liked. We met him I guess in the early 70s. Jacob Lawrence I’ve always liked. I like [Sam] Middleton. I like Van Gogh, got Van Goghs all over the house here, lots of other people

D: What about musicians?

J: Musicians too numerous to name. There is this cat on guitar from Boston, Adam Williams, and lot of new young people coming up . Maybe I’m just an old fogey , I’ve got to get with these young people, but the old stuff I’m content with.

D: Such as?

J: Well Bird, of course, and Diz. Ellington when he isn’t so busy being disonant. There’s those long ,stagey lines and lots of brass and stuff like that. Wes Montgomery, Ron Carter, Chubby Jackson, Bud Powell Teddy Wilson, just a whole bunch of people.

D: You like a lot of folks of your generation went to college after the war on the GI bill, and in doing that you were already kind of changing your life in a sense in terms of careers and class that sort of thing from the family in which you grew up. But then to go from that leap to ending up becoming a writer. It’s one thing if Johnny is going to get a college job, but now Johnny is going to become a writer? What the hell is that? Did you have any awarness at the time what an absurb leap that was?

J: It wasn’t absurd in the beginning. You know when I was going to school I was also working as a night orderly at Memorial Hospital. I was working at Oberdorfer foundry during the summer, and I was so good that they gave me a regular job on the night shift. I was a vegtable clerk at Loblaw’s, and I only wound up getting a job at the welfare department after sort of falling back into the swamp. You know this is what everybody else had done in my family. You took any job that came your way.

Actually, I didn’t do that. I remember there was a job at a tuxedo rental place on the corner of Montgomery and Warren Street, just off it, and I remember I went down to apply for that job and there must have been 500 pairs of shoes on the floor that needed shining. I turned around and left. See, in a sense, the idea of having gone to college didn’t make a real dent, and I can understand that the important thing was to have a job to bring in the money. [My mother] Ola wanted me to learn how to become a florist with Al Markowitz. Al Markowitz and his wife had a son, they acturally had two sons, but Bernie was a pain in the ass. My brother, Joe, would go with me and we’d work around the shop and Bernie would tell Joe to take a bucket of water and go out and wash his car wheels. The first time he did that I couldn’ believe it, and I went out there and said, "Wash your own fucking car wheels," and I threw the water over and dragged Joe from that, and that was it for Markowitz.

So that it was a long time getting to that welfare gig, and even then it was doubling up. I was running an elevator in the Loew Building at night, when I got on with Doug Johnson Associates, public relations. And then the world fell apart and I went to California. That was like trudging through the Mohave Desert at night. That was an incrediable year for me, Jesus Christ. But I got back and I latched onto a job at a small publishing house, and after a year I asked for a raise and they said that’s it, you’re fired. And I did a number of things and I survived. That I think everybody could understand, but the writing as you know a lot of the relatives would say, "Are you still doing that writing?" like it was a part-time job or something. And I said yes, sure. My father never spoke to me about writing , never asked for a book and I never gave him one maybe because he never asked. But Ola seemed to catch on faster than anybody else.

D: What was it like growing up in Syracuse?

J: Well, that was an experience. I remember living in a place when I was very small down on Washington Street, two houses from the old Rescue Mission. The New York Central used to come right down that street so you’d see the redcaps getting ready for the station hanging doors and waving. The first time I saw that train I was scared shitless. I hit the steps screaming and my mother rushed out of the house and picked me up.

I think that at the time I started kindgarten that must have been when a number of black folks had moved into the 15th ward . I still remember the first day of going to kindgarten being picked up by Miss Riley. I had things a little screwed up in that kindergarten class because some kids would get little containers of milk and graham crackers, and I would say to myself, how come I’m not getting some of that? And it later developed in 4th, 5th grade this was for really poor kids. Oh, I’m saying to myself, I guess we were not that poor. The schools were then involved in the subtle kind of hygienic existence. They would pass out little bars of Lifebuoy soap and Dr. Lyons tooth powder because there were a lot of immigrants coming in and they had to somehow measure up to American standards.

I remember the gym teacher, Mr Andrews, a mean motherfucker, boy, and that gave me my first clue as to how rotten some teachers could be. But most of the other teachers were pretty good. And I loved the English teacher, Miss Lord. We all did. The last half hour of class she would read from adventure novels. She had us so much under her spell that she’d ask a question the kids would run to the front of class to answer. I was a musician at that time too. Whenever we had an ice cream social I would play the triangle and the water whistle.

D: What is a water whistle?

J: It’s a whistle that had water and little hole and whtever and made a sound like beeep beeep.

It’s become kind of cliché now because everybody my age speaks about it, that kind of cohesive element you had on the block. Everybody knew everybody else, knew everybody’s children and everybody would squeal on you if you hadn’t behaved when your parents were gone. But I am not sure what was wrong with me, whether I was unhappy or just restless or stubborn or whatever, but I would take off at a moment ’s notice, just hit the bricks, man. Everybody would be looking for me through the night.

D: Where did you go?

J: Up on the hill, Thornden Park, just hang out, sleep under the bushes. I never did this in the winter. Come home and get my ass beat and things would be okay for a while. The church was very important. I would wind up getting usually the longest poem to read, Christmas, Easter, whatever. I remember I got a poem in which the speaker was some kind of warrior. I was really innovative, so I went out and got the top of a garbage can, painted it and that was going to be my shield, and I got some old lathing and made myself a sword. So I’m standing up there and the paint hadn’t really dried, I’m in my Buster Brown suit, and the paint from my sword is getting on my pants.

I remember the dinners they use to have and then all the white folks would come because everybody was working for white folks and they would all come for Sunday dinner. Then we would go to the Resuce Mission in the afternoon and these drunks would get up and tell how God had saved them and stuff like that. At one point religion got to me (I may have told you this), so I went home and—we had this china closet that I had learned to pry open with a knife to get peanut butter and cakes and pies, while Ola was wondering why the cake was shrinking, why the pie was shrinking, and my old man used to keep his booze in there. I pried it open, got the booze and poured it all down the drain. "So what the fuck happened here?" I said drinking is evil so I threw it all away. "What!" pow pow pow That taught me about the dangers of being too religious.

D: I’ve always gotten the impression on some level anyway, that your Syracuse was more intergrated or multicultural than mine and certainly more than it is now. What do you think?

J: It was and I think what happened was that the war brought in not only people to work—there still were not that many jobs for black people, the plants were still segregated, not that many jobs for men or women. But there was still agriculture, and you had an influx of black migrants who some people used to call pea pickers or bean pickers and as a matter of fact I think I wrote about this someplace. I had a buddy who worked on the Post Standard, Walter Carroll, and I was at the welfare department and I would sneak him around at night and let him see how these people were living and he did what was then a a big exposé. But I think that influx number one occurred, and number two, the large number of Jewish perople in the community began to move out. Those two things worked in tandem, and there were more and more younger people moving in.

D: Where did you get the sense of family pride that you conveyed to us?

J: I’m not sure where I got it from because it was a struggle for the folks to maintain it there with just about everybody breaking up and some people going to jail. My uncle Ernest went to jail and [Uncle] Bud was running around and eveybody said Bud was nuts and to a large extent he was, but in that respect I think iIcan understand the pressures. And I’m not sure how hard eveybody tried but I guess they tried, because I remember people from my father’s family gatherings we had and people from my mother’s family and sometimes they were together and I know the families didn’t get along that well. I think Ola’s family sort of looked down on them because they didn’t own anything, and her family had owned this 88 acres in Mississippi and it has been tough holding on to that. But they tried—didn’t always work— and because my relationship with my immediate family had been interrupted I was more or less determined that something had to happen so I did my best.

D: We go back to, what did you figure, 1832 in Syracuse?

J: Well that was the 1803 thing, and you said look at it again and maybe it’s 1863, but then that would eliminate my father’s great uncle, and I think Gorman Williams married Margaret Smallwood in 1838, which would be some time after that.

D: Have any idea how those folks got there and what they were doing there?

J: The mystery is after Roots everybody started talking about where they came from and Ola would do that occassionally when she was raconteuring, but she would be talking so fast you’d miss this that and whatever and sometimes [my Aunt] Elizabeth would fill in. But on my father’s side the only time he would talk about family was about the last 5 years of his life and he seemed pretty resistant about doing that. I never pushed it .

D: Up here I am reminded of the line in The Junior Bachlor Society about black folks being land people and being jived into the cities. Where did you get your appreciation of land? Certainly it wasn’t from moving from house to house in the 15 ward in Syracuse?

J: I like being outside camping. There was nothing romantic I got from Ola about those 88 acres down there; she was talking about the rattle snakes all over the place and up in the chimmney. And the white man wanting to take the land which at one time he did take. He traded his land, this neighbor do you know that story? There was some rumor about oil down there, and he traded my grandfather, and when he didn’t find oil he traded back at the point of a shotgun. I don’t know where that land thing came from.

D: How did the war change you?

J: In Syracuse the kind of racism you get is not really worth mentioning. You wouldn’t even call it racism; you’d call it pique. The fact is that eveybody got along. That was not true in the Navy, and I think for the very first time I came in contact with deadly racism. And i still wound up in trouble. I think I had one captain’s mast at great ? I had a summary court martial in Guam; that was five days piss and punk [bread and water] and three days piss and punk on the LST ???? on the way home. It made me angry and yet there wasn’t too much I could do about it. I think we all recognized that, particularly when you were moving around as I was trying to catch an outfit that didn’t want to let itself be caught by you. They didn’t want any black people on that attack transport. So I just wound up going from outfit to outfit, a lot of them white, and looking like someone dumped a ton of coal in the artic snow and shit like that.

I ’m really lucky I’m alive because I’ve been in chow halls where there wasn’t a black face and jumped over serving lines to jump at some guys who were laughing at me because I was black. But I bluffed them. I guess he must have thought, "Shit, if this nigger is bad enought to jump up here he may hurt me."

Then going over to that tent and having those crackers put that .45 to my head. I remember the three names until today: Cameron, who was some bad-skinned blond white boy from Texas, Dobie who was some kind of Greek who was damned near black as I was and a wall-eyed fat fucker named Williams from Mississippi.

D: No relation.

J: No. They were in a tent next to mine with this loud, racuous southern laughter, nigger jokes and so on and so forth and three friends of mine, a black guy named Atkins from Chicago, black guy named Owens from Birimingham and there was a white guy in the tent named Jenkins who was from Texas. And they just kept it up until I finally said to Atkins and Owens, "Let’s go over to the tent and tell them to stop it." And Akins if they don’t stop in 15 minutes then we’ll go, and Jenkins said oh forget it, forget it, and so they kept it up. In fifteen minutes I said to Atkins and Owens let’s go. Sleep sounds: they werepretneding to be asleep. So I had to go over myself and when I walked in and told them to cut out this shit, Williams pulled out this .45—I had never been that close to a .45—and put it right up to my head and then eveybody else in their tent got scared. There was going to be a big mess. I just stood my ground, my legs felt like Jell-O. Finally I turned around and sort of strolled out—but the tent quieted down.

I am not sure I told you what one of them said to me later. I ran across Cameron up on Guam, and he said, "You know something, Williams?" and I was just scalding ’cause I see he ain’t got his buddies with him. He said, "You ain’t like those other boys." I said, "What you mean? Yes I am, I’m just like them, maybe I’m luckier." And the son of a bitch—he had lost his girfriend, she had written him a Dear John—and he was crying on my shoulder about this shit.

I don’t know what ever happened to them, but the other side of that coin is that when I went on a one-man draft out to the coast, I got off the train in San Francisco, and I’m trying to find Treasure Island, that’s where the base was. This old master sergeant —crusty white guy ,there were not too many black marines then—said "Come with me, I’ll get you to Treasure Island." The cat had been on Guadalcanal, he had ribbons from his collar bone down to his tit and he took me. Said, "Let’s make a few stops before we head out." Took me to all these bars in San Francisco and I’d see these bartenders at the momemt he entered with me, but they wouldn’t say anything to him and he’d say, "Give the kid a drink," and they would serve me.

Now I really didn’t know how bad San Francisco was until I met this kid from Brooklyn, Walter Timothy who got killed on Bunker Hill off Okinawa. Wally was in the same situation as I was; he was looking for a ship, too. He loved Tommy Dorsey boogie woogie, shaking his skinny ass, and we used to run into San Francisco and Oakland whenever we had liberty together. We’d go in white places, they would throw us out, we’d go in black places, they would throw us out. We ’d be walking down the street waiting for the last train back to Treasure Island. There were some real killers I met, but it was the first time in my life that I had run into that stuff. Some people didn’t make it, but I made it.

D: What did you learn about yourself in those times?

J: Well, in retrospect I kind of liked myself for surviving, for one thing ,and for not putting up with too much shit. That may have come naturally; I think it probably did. I still did not know a great deal about the world. I just knew essentially about conflict, and this new thing that hit me, what we then called prejudice.

D: How and why did you get started teaching?

J: Quite By accident I think, although recalling a couple of things even when I was in Syracuse with the welfare department, I had sort of flirted with the young progressive, young communist league or something. And I say flirted, without going to a single meeting, but I could always talk to those people. Somone from Cornell asked me to address a couple of groups of workers. I don’t even remember what I said; I was just nervous as hell.

D: When was this?

J: Right after iIgot out of school. I don’t remember where the meetings were held, but I do remember talking to a couple of them.

Before that, I would coach the Dunbar Center football team. I remember when I was on leave from the Navy once I went back to Syracuse during the fall just before football season opened. I went out to watch the drill at Kirk Park and Pat King? the coach said, hey Joe—they called me Joe—come and show these guys how to run this double wing offense. So I went over in my uniform and did this little stuff. And I was in the Scouts for so long as a troop leader and then camp counselor, I guess in some ways it was always in there, but academically that started at City Collegein ’68 .

D: How? You needed the job? You were interested?

J: I didn’t need the job, but I was interested in it, and it was teaching writing, article writing, and Ed vulpoe(?) who was president of the school then called and asked me. So I went up and met people like James Hatch, Leo Helman, a lot of good people. Jim Emannual and I did the course, and I had a class the night or the day after Martin Luther King got killed. I remember standing in the class and I was really pissed and I just told them I don’t think I should be teaching white students anymore. There were about four black students in the class. There was just a silence as though they were just putting up with me, but that soon passed.

D: When did you fall into the rhythm of your twenty-five years of distinguished professorship? When did it become a regualr thing?

J: After City College I went to the College of the Virgin Islands, and what I was teaching the students were afraid of, so they went to the administration and said, oh you should hear what Mr. Williams is saying about you people. And then they wouldn’t let me do a lecture in town in Charlotte Amalie, and I said hey this is very intersting, so we spent the summer just hanging out on the beach and driving around. I think in ’72 or’ 73 George Gorman called— George was the husband of a woman that [my wife] Lori had worked with and they were still very close and as a result George and I became close. He said how would you like a distinguished professorship? I said what the hell is that? He said over here at Laguardia Community College, it’s a new school and this is what they pay and this is what you have to do. Why don’t you come over and give a few lectures? I said, so you can feel me out, and he said yes. So I went over and did these raps and they came up with this distinguished professorship. The money was good, but it pissed everybody else off because I had just come in off the street and I didn’t know anything about academic politics. People would come to me and say would you talk to the president about this and that and like a fool if it felt right then I would go talk to Joe Shanker, the president—not that anything changed. Well it got clear to me that I was there to attract students of color in this new community college plan and to an extent I guess it worked. I put up with that until ’78 and then iIwent up to Boston University for a year, communting. In the mean time I had the done the University of Hawaii and Santa Barbara. I thought, hey, this is pretty cool.

D: How did Rutgers come about?

J: I didn’t want to go back, after Boston—I did that on a year’s leave, and I didn’t want to go back to Laguardia. I was at a party in Montclair and there were three pople there from Rutgers who asked me if I would be interested in going there and I said why not, half hour from home. So the next thing I knew I was getting letters from the president of the school, and I started Rutgers Newark in ’79. as a full professor, not a distinguished professor and of course there to was a kind of resentment, but I knew my way around a little better then. The rest is history.

D: How did the students as a whole change over the 25 years you were teaching ?

J: I think there was less seriousness about schooling. Just the ieda of getting over, doing just enough to get over seemed to become the mode of many students. I also think that 50 years of cold war and everybody understanding perhaps even subconsciously that they could be gone the next minute had to affect the way people, particularly students, thought about their future. I think that had a great deal to do with the attitudes of many people and that in a sense has continued today. I was starting to work with a dean to put together some classes that dealt with precicely that, but they felt it was not quite apropo and it was dropped.

D: You have written about academic politics in Colleagues. What was your worst experience with that?

J: My worst experience was working with a totally incompetent man. Not only was he incompetent—I don’t see how he lasted in his field—but he was an evil man. He played around with grades, made students to certain things in order to get grades, and I’m not talking about sex or anything like that. I mean they had to really kiss his ass in order to get decent grades. His student evaluations were always bad when they showed up in the file anyway, and everybody ignored this man. Even when he was caught in a criminal act they just ignored him and I said, shit ,forget this.

There was one guy whose office I finally got who was so old and who shuffled about and who seemed never to make sense even in meetings. He worked until he died on the job walking to school one day . And the man should have been gone a long long while. We had people there who had been associate profeessors for 20 years, you looked at their publication record and it was about as slim as a book of matches; didn’t seem to matter. And meanwhile there were other people, particulary minority faculty, they were always pushing to get published. If they didn’t or got one bad evaluation everybody was on their ass, and I said, oh, Christ.

D: What were some of your more satifying experiences as a teacher?

J: Well, to see some kids really get through it. To see kids who had managed to survive all the academic crap and aadministration politics and graduate. I went to only one graduation while I was [at Rutgers], but I was always invited. I was invited to weddings ,and kids would come back and bring their children and stuff like that. So that was pretty cool. And I had a couple of good collegues, and we sort of cried on each others’ shoulders. But otherwise it was a jungle.

D: I asked you about students in general. How did you find black students over the time you were teaching?

J: Not really on the whole as prepared as a number of white students, and remember you’re talking about Newark, so most of the black students were very much in the minority . You talk Rutgers Newark, and you think of an all-black school, and that was not at all true. Most of our students were the children of white, blue-collar workers from Bellville and places like that. You got a heavy student of color population in the eventing, but these people for the most part were really geared to being taught, to learning what was really going on. But the undergraduates were not well prepared. That’s why we had the academic studies foundation to drill them in all these skills, math, language and things like that, and that had not improved. In fact, as the Newark schools got worse the students got worse. Very often their view of getting bad comments or bad grades was to always challenge the teacher. So a couple of times when they made complaints about me the process called for me sitting down and having an interview with them, which I always taped and told them it was being taped. Where I explained to them what had happened, how they had failed. And then it would go to the chair and that would be it; they would just flunk. A couple of people were so salty—I got letters for a couple of years from some students. But nothing worse than that. Nobody tried to kneecap me or take me out

D: Your teaching career pretty much coincided with the last twenty five years of affermitive action in education How do you think that has worked?

J: The community college system was set up because there was a sense that anybody who wanted an education should be able to take it, so even at Laguardia there were lots of students who were just along for the ride and if they had an interesting course or good teacher then they really got into stride. But a lot of them even there were just getting over. You do a year, then get out and work for a year, then you come back and finish your second year. And many the time I would assign stuff to be read and come into the class and start asking questions and nobody would have read the work. I’d get so pissed, I’d say, okay, you people read; I’m going out for coffee. And that’s what I did. There were classes at Rutgers with juniors and seniors where people wouldn’t do the work, and I’d just leave the class. Let them know how disgusted I was. That didn’t always help. Sometimes it did, but not always.

In terms of the faculty, I was on the affrimative action committee and I saw some of the stuff that was going on. For example a black associate professor who wanted to be in the New York area would be willing to take an assistant professorship to come to Rutgers Newark. I’d say we can’t accept this. We either have the person on the same level or not at all, instead of hiring whites who are assistant professors and giving them an associate professorship because they came here. I was only on that committee for a year, and I guess I was a real pain in the ass because after that I was never asked to serve.

D: What do you make of the backlash to affirmative action nationwide—and the California decision?

J: I think it’s all bullshit. Affirmitve action as I understand it was really created to redress disadvantages African Americans had suffered throughout American history, but everybody got on this very slender raft. The main thing that began to sink it was gender. When they opened it to women—and I’m not saying they should not have but perhaps there should have been another program to address that—but they opened to women and they came on board in droves. You know the phrase "twofors"— if you got a black woman you got two for one and all of that tallied up in the stats. And then you got Latinos and Asians, and some Asians would come from China on these graduate fellowships to teach and couldn’t even speak English well, and the kids would be bitching and carrying on. Idon’t think it was thoroughly examined enough to kill it in California or anywhere else. To modify it, yes, but you cannot modify a program like that now after 30 years.

D: What made you stop teaching?

J: I was really getting a little tired and a little bored. Teaching journalism, it took five years, for example, for us to get the equipment I knew we needed to be any good at teaching this. Then we couldn’t get the support for the graduate writing program, which by the way was bringing in large numbers of students for the overall English graduate program. There seemed to be very little vision for the future. People were doing things hit and miss, and I was fighting them all the way along. I was getting to be a pain in the ass, but they were happy to have me because I was black, had all this rank and I was publishing. And they could always say —they never did it to my face, but I’m sure they did it off the record—see there, we got one, and he’s great. I just got tired of fighting it . When I left they said you don’t have to retire. I said I know that, and as you know i primed the pump about three years before I left in order to get that chair. And when I told them they weren’t making my stipend large enough, they said okay, we’ll give you some more. I guess they hoped that would deter me from leaving. But I had really had it.

D: What have you been doing since you stopped?

J: I’ve been very busy, as a matter of fact. I did that year at Bard College. I found—I may be wrong, essentially the same thing—that it was more important that I was black than my being a good teacher. First semester I flunked a third of my class and some dean wanted to talk to me. I explained to him why; people hadn’t done the work, and that was it. When I signed on they wanted me to be there for quite a while, and I suggested let’s do a year and let’s see if I like you and you like me. A year was enough . Since then I’ve been finishing up Colleagues, put together several proposals that went nowhere, about interracial marriages, interracial adoptions, black soliders. And working on this opera.

D: Talk about the opera.

J: Leslie Burgess is a flutist in Philadelphia. I had worked with him on an opera that Duke Ellington had not completed, called Baby Doll, and we were working pretty well. We ran into problems with Mercer [Ellington], who had asked us to do it. Mercer did not want to pay the money and was ducking and dodging, so we decided it was a lost cause. [Later] Leslie was doing this work for Opera Columbus and they wanted this new opera. They had some Lila (?) Wallace Fund money, and they actually thought I’d be interested. It’s on slavery in the U.S., and I said yeah, and we sat down and talked over some ideas. He came to Teaneck, and so I started putting together this book about a couple of characters who are part mythic and part real. Each winds up dead, but their spirits are looking for each other, throughout the play on different levels. But as they move through history they encounter people like Nat Turner and Frederick Douglass and [Gabriel] Prosser and John Brown. Originally the title was Many Thousand Gone, but we had some problems with that title because there are so many versions of that. At the moment it is called Windward Passages, so we’ll see what happens with that. It’s two acts and it’s supposed to debut in 1996. I’m all done at least in terms of the first draft of the book and lyrics. Now Leslie has to sit down and get his stuff together.

D: What was it like working on an opera?

J: The story fleshes itself out, but writing the lyrics to enhance the story to flesh it out even more is very exciting. Again, it is that kind of thing poetry does for you. You have to be succinct and sometimes subtle and sometimes overt. The first one I did was Nat Turner, and that wasn’t so damned overt. Later I’m trying to get into aspects most things don’t cover: relationships between white women and black women, white women who are friends and wives of the planters and black women who are slaves. I think we’ve done that pretty well. Without stating the period it’s obviously from 1700 through late 1800, up until the Civil War when the play ends. It ends at the onset of the Civil War.

D: Have you heard pieces with your words set to music?

J: I can’t make the words out too well. While some of it is pretty modern, there are elments that tend to be very operatic and when those parts are sung I just don’t understand them. I think it’s essentially as Leslie has said, it’s the recording and technological conditions under which [the tapes I have] were made.

D: What kind of negative reactions professionally have you gotten over the years as a result of your marriage to Lori?

D: That’s hard for me to know, because it never appears in print. It is not anything that people write about but you get word. We were talking to Michele Fabre in Tenerife and his wife asked something about is it good for your career to be married to a white woman? Michele piped up even before she finished, No! And he’s in France, not even in New York, but of course he’s had the experience of [Chester] Himes and Wright and others. There have been references off the wall, references to my marriage and some pieces occassionally, but generally it is word of mouth that circulates.

As I have said my point of view is if you don’t like it, you can kiss my ass and you can look but don’t touch. And that goes out not only for black people but white people as well, and I have always maintained that . People have not bothered me physically. I guess I hold the same view as people like Ishmael Reed and others who are in the same situation. It’s really there, but Lori doesn’t seem to feel it as keenly as back in the ’60s and ’70s. I had twelve years between marriages, so I had ample time to be snapped up by anyone and she was the only one who did.

D: I remember in the ’60s you did this TV program on PBS, "Omowale: The Child Returns Home." The conclusion was that after visiting Africa you were coming back to America, but that was coming home. How did you reach that conclusion at the time and do you still hold that view?

J: Yeah, I still hold the same view even more strongly now because I understand that black people have been here far longer than most immigrants. In fact, some old historians that no one reads anymore but since I have a penchant for history I collect all these old books, most of them do declare that there were more black people in early America than there were white people. And then the immigrants began coming and continued to come, so I felt very strongly that given both parts of the family we had been here long enough to most certainly call it home. Also I simply felt that my experiences in Africa—although I never expected as much from Africa as, say, Richard Wright did—fell far below what I thought would happen.

D: What does that mean to you at this point being—more than ever convinced of your Americaness, given the fucked up state of the country?

J: Misery. It gives me tsouris. It gives me ulcers. It gives me stomach spasms, backaches .

D: I’ve noticed in your books these fascinating and often obsecure historical details that you sprinkle through there. It’s almost as if you have discovered these facts and can’t wait to share them with us, the readers. How did that habit get started?

J: I’m not sure it’s a habit, and I only use them when appropriate. Are you talking about Colleagues—the writing professor, Randall, who is married to this Spanish woman and he is trying to get her to get over her phobia of Puerto Ricans and Mexicans and stuff and he mentions the conquistors?

D: It’s not that it’s inappropriate, but its there and noticeable. It’s a form of teaching. Are you conscious of it?

J: Sometimes I’m conscious of it, and I think it’s very important if you’ve got the right space in which to do it—why not? People I admire like Carponiter and Borges do it all the time. Its sort of like adding some cement to this structure that they’re building.

D: You read a lot of history. Are there particular areas of the world or time periods that you spend a lot of time on that you are especially fascinated with?

J: I guess prehistorical periods and the early civilizations. But then the renaissance becomes very intriguing, and this whole business of slavery began essentially during the renaissance period. the age of enlightment, the American revolution, the French revolution. You’ve got this whole school of the canon talking about the promise of humanity and how bright Europe was shining light over the whole world, and you’ve got this undergirding of economic traffic going on. So you’re always looking at contridicitions between now and then and then and then in various cultural situations. That’s what I like to look at and compare.

Looking at it from an Afrocentric point of view, one of the things I have discovered is the extent of the African or black influence in Europe. Lori will tell you when we’re there and going through castles and whatever I’m trotting around with a camera looking for obscure black faces in carvings, and they are all over the place . This February when we were in Tenerife I was looking for signs of that. Of course what those people there say is that they are all descended from Berbers. What no one ever says is that the Berbers and black Africans further south were completely mixed. So people always claim to be decended from Berbers or Celts and yet you can go to parts of England and find evidence—historians have written about this, the black presence throughout all of Europe. And what always puzzles me and angers me too is that this high-hat European superiority is essentially built on something that all of us really share.. They just say no, it’s us and us alone.

D: Why after 25 years of black studies are these kinds of facts and analyses still so rare and surprising?

J: Because they don’t have a platform. If you take a white scholar like Martin Bernal who’s done fascinating work in this area, no one is giving him credit. As a matter of fact they set out to do a hatchet job on his very first book. Most blacks would read Bernal with the idea that he is vindicating the extent and longevity of the African influence in Europe. That’s not what he’s doing. What he’s saying is that there is extensive interplay between these cultures. He is not into superiority, which in a way is much better. We know that cultures always borrow from each other and influence one another and that’s his point. The scholars who have a vested interest in A or B don’t give a damn about Bernal’s C. And he is at the top of the heap in terms of scholars who would be accepted.

People are so invested in the present, and because white people tend to own the present they make the assumption and demand that we also make the assumption that that’s the way it always was.

D: You have also been interested in things extraterrestrial. You gaze at the stars, you think about things out there although you’ve never writen science fiction per se, you have what I would call a science fiction mind at times. Do you have any theories?

J: I find the older I get the more difficult I find it to believe that this is the only blessed jewel in the sky. I can’t believe it any longer. As for the possibility of travel between planents I’m open to that. There are just too many damn questions that nobody wants to bother with on this earth for me to conclude that this is it, period. Certain things that have happened, certain things that have been found, certain cultures, certain technologies within certain cultures nobody wants to be bothered with, and yet they are there. I think one of the problems comtemporary civilizations have is that they are not interested in the past as a learning tool about making progress in the present. They just ignore it. I’ve done kind of a long poem that I call "Replicatas." It all has to do with this earth and its people being out of tune with whatever fine-tunes the rest of the universe and our problem may be that because we can’t get in tune we are lost. I know exactly where that stems from, the film the Forbidden Planet that came out in the 50s. They were talking about the evil that had occurred on this planet after such a long time and that is what destroyed it. That’s been cooking with me for about 30 or so years and I feel essentially the same way.

D: What are your thoughts on the future for the country or for the planet?

J: You know Spengler says that demoracy is pretty much a way station, on the way to fascism or Caesarism as he calls it. We have to understand that demoracy is still an evolving political concept and that the distance we have gained from Greece to now is relatively short. When those guys were talking demoracy in Greece and the polis, the population, the people—the people were slaves working the mines there. And then Plato also says, you know this bullshit we are telling people about blah blah, well that really ain’t the way it is. What we really think is so on and so forth. Well that continues until today. So we either realize that we’re an evolving demoracy and perhaps have to go to a radical demoracy, bypassing fascism, or go through fascism before we can return to the problem of making democracy work again.

At the moment it looks as though we are headed for fascism. And I say this with some unhappy certainty because of the role of the media in all of this. The media is not a help to demoracy. Demoracy means nothing if you don’t have any money and you can’t operate in it. If you are rich democracy is a wonderful thing; it helps you become richer. And the media has always had the role of being on the side of the power brokers, and it’s more concentrated, more power, more communications more rapidly, they can lie to us faster withhold the truth with greater ease and on and on. So here we are. Which way is it going to be, fascism or radical demoracy?

D: Is there still hope, speaking of the media, for emerging technologies? They have the potential, at least theoritically, to bypass, some of the established media power and allow for more democratic communication. Do you see that as a possibility?

J: I don’t see that as a possibility. Number one, all communities use telephone lines. All are subject to attacks of virus, and if you don’t want to be bothered with a virus all you have to do is cut off the lines and that’s it. In addition to that, the nets have revealed a horrible tendency to be as racist and as fascist—that is, some people who are using it—as any other segment of society. So I don’t see all that great big hope in the use of computers. I know that that’s what everybody says, but I’ve seen otherwise and I can’t go along with that program. I don’t know how other than by putting bodies in the street in a more or less peaceful fashion to achieve democracy, because that’s what demoracy demands. That people make their voices heard in public not hidden behind some computer. Just get out in the street and do what you’ve got to do.

D: Is it possible for this country ever to have a multicultural democracy? We see now routine backlash against affirmative action and the whole concept of multiculturalism as if it were some subversive virus. But the country has always been ethnically diverse. That seems to be one of the great questions for this country, whether that can work. What do you think?

J: If it doesn’t work we are dead, to put it simply. Because it’s too ingrained, whether it was under the most beneficent arrangements or not, speaking of slavery and what so many immigrant groups had to go through to achieve any kind of status here. And if we do not have a multicultural society we will not exist. This society is probably more multicultural than Rome ever was, and Rome expanded over the known world. The problem with the decline of Rome was not, as some historians claim, that it was a multicultural society. It had to do with the politicians buying power and selling power, betrayal and betrayal. But the multiculturalism has got to exist or the United States does not exist. Period.

After all [the U.S.] got itself into this multicultural business through econcomic greed. What happened to the Indians and the slave trade that lasted for 400 years. And then you had the Chinese on the west coast and you had to populate the country so just about anybody who wanted to come here who can claim a bit of Spanish or French blood came, and there you are. Europe was actually the "white bastion" but even Europe since World War II has changed immensely. It is a hell of a lot less white than it was before the war. The French and the British, in Spain, Germany, Italy—the whole place has changed. The fact the US was a shining example of a multicultural existence probably did not hurt European acceptance of other than Europeans living there. Somebody did a novel—William Melvin Kelly—about what if all the African Americans leave and what it would look like. I think it would be a pretty stupid place without all those multicultural groups going. But the good thing would be all the whites could start fighting each other like they used to do in Europe and maybe they would wipe each other out and then we could come back and enjoy it.

You have to get rid of some politicans who have always used these issues to get elected and create difference within the population, not only for their own benefit but the benefit of certain business groups. What I think would be the most important move in politics is congressional reform, where you cannot buy an office. No one can buy an office. That is really what sunk Rome, just buying political office, and you usually buy somebody who is not any good for the people because the politican is purchased by a business interest. How could he or she serve the people? It’s impossible .

D: How do we get that?

J: We can’t get it through congressional reform because congress people certainly are not going to do that. I think people perhaps are beginning to demonstrate that they are not going to go along with it for much longer in terms of the numbers in which they vote. They’re saying the political process sucks and I’m not going to bother with it. Now this is a two edged sword. Number one it says you don’t have a voice, and number two it allows the people who are powerful to exert even more power because there are fewer bodies in the arena. I don’t know what the answer is.

D: Well that’s not very helpful. (laughter) You’re supposed to be being wise here.

J: I’m sorry.