-

Posts

2,415 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

91

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

Why I Keep Coming Back to Reconstruction

By Jamelle BouieOpinion Columnist

I write frequently about the Reconstruction period after the Civil War, not to make predictions or analogies but to show how a previous generation of Americans grappled with their own set of questions about the scope and reach of our Constitution, our government and our democracy.

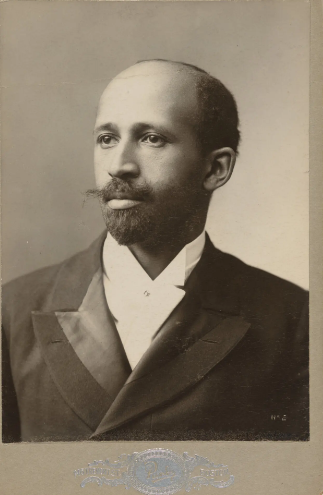

The scholarship on Reconstruction is vast and comprehensive. But my touchstone for thinking about the period continues to be W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Black Reconstruction,” published in 1935 after years of painstaking research that was often inhibited by segregation and the racism of Southern institutions of higher education.

I return to Du Bois, even as I read more recent work, because he offers a framework that is useful, I think, for analyzing the struggle for democracy in our own time.

The central conceit of Du Bois’s landmark study — whose full title is “Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880” — is that the period was a grand struggle between “two theories of the future of America,” rooted in the relationship of American labor to American democracy.

“What were to be the limits of democratic control in the United States?” Du Bois asks. “Was the rule of the mass of Americans to be unlimited, and the right to rule extended to all men regardless of race and color?” And if not, he continues, “How would property and privilege be protected?”

On one side in the conflict over these questions was “an autocracy determined at any price to amass wealth and power”; on the other was an “abolition-democracy based on freedom, intelligence and power for all men.”

The term “abolition-democracy” began with Du Bois and is worth further exploration.

Abolition-democracy, Du Bois writes, was the “liberal movement among both laborers and small capitalists” who saw “the danger of slavery to both capital and labor.” Its standard-bearers were abolitionists like Wendell Phillips and radical antislavery politicians like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, and in its eyes, “the only real object” of the Civil War was the abolition of slavery and “it was convinced that this could be thoroughly accomplished only if the emancipated Negroes became free citizens and voters.”

It was also clear to some within abolition-democracy that “freedom in order to be free required a minimum of capital in addition to political rights.” In this way, abolition-democracy was an anticipation of social democratic ideology, although few of its proponents, in Du Bois’s view, grasped the full significance of their analysis of the relationship between political freedom, civil rights and economic security.

Opposing abolition-democracy, in Du Bois’s telling, were the reactionaries of the former Confederate South who sought to “re-establish slavery by force.” The South, he writes, “opposed Negro education, opposed land and capital for Negroes, and violently and bitterly opposed any political power. It fought every conception inch by inch: no real emancipation, limited civil rights, no Negro schools, no votes for Negroes.”

Between these two sides lay Northern industry and capital. It wanted profits and it would join whichever force enabled it to expand its power and reach. Initially, this meant abolition-democracy, as Northern industry feared the return of a South that might threaten its political and economic dominance. It “swung inevitably toward democracy” rather than allow the “continuation of Southern oligarchy,” Du Bois writes.

It’s here that we see the contradiction inherent in the alliance between Northern industry and abolition-democracy. The machinery of democracy in the South “put such power in the hands of Southern labor that, with intelligent and unselfish leadership and a clarifying ideal, it could have rebuilt the economic foundations of Southern society, confiscated and redistributed wealth, and built a real democracy of industry for the masses of men.”

This — the extent to which democracy in the South threatened to undermine the imperatives of capital — was simply too much for Northern industry to bear. And so it turned against abolition-democracy, already faltering as it was in the face of Southern reaction. “Brute force was allowed to use its unchecked power,” Du Bois writes, “to destroy the possibility of democracy in the South, and thereby make the transition from democracy to plutocracy all the easier and more inevitable.”

In the end, “it was not race and culture calling out of the South in 1876; it was property and privilege, shrieking to its kind, and privilege and property heard and recognized the voice of its own.” What killed Reconstruction — beyond the ideological limitations of its champions and the vehemence of its opponents — was a “counterrevolution of property,” North and South.

Why is this still a useful framework for understanding the United States, close to a century after Du Bois conceived and developed this argument? As a concept, abolition-democracy captures something vital and important: Democratic life cannot flourish as long as it is bound by and shaped around hierarchies of status. The fight for political equality cannot be separated from the fight for equality more broadly.

In other words, the reason I keep coming back to “Black Reconstruction” is that Du Bois’s mode of analysis can help us (or, at least, me) look past so much of the ephemera of our politics to focus on what matters most: the roles of power, privilege and, most important, capital in shaping our political order and structuring our conflicts with one another.

ARTICLE

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/25/opinion/reconstruction-civil-war-du-bois.htmlMY THOUGHTS

The question is simple. If all humans are equal in a space then how do the poor not rip from the rich or how do the rich not enslave the poor? The USA has no answer. Never had one. In Haiti or France or Russia the poor ripped from the rich. In the USA... the lower rich ripped from the upper rich, but the poor of the usa still had needs and from the war between the states to the gregorian year two thousand and twenty two, the poor have tried to merit to satisfaction while not taking from the rich. But, patience is a thing rarely stated when people talk of peace. and absent patience, the poor can't wait to take, the rich can't wait to enslave.

Biden and Trump Share One Thing

Oct. 24, 2022

By Yuval LevinMr. Levin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, is a contributing Opinion writer.

Back in January, looking ahead to the midterm election year, President Biden said that he expected to be featured prominently by Democrats running for Congress. “I’m going to be out on the road a lot, making the case around the country, with my colleagues who are up for re-election,” he predicted.

It has not turned out that way. Instead, many Democratic candidates have practiced the delicate dance that politicians of both parties have had to master over the past two decades — keeping their distance from a president of their own party while not openly repudiating him.

The four presidents we have had so far in this century have been peculiarly unpopular. George W. Bush had a stretch of high approval after the Sept. 11 attacks but spent much of his second term underwater (often deeply). A chart of Barack Obama’s public approval looks faintly like a W — briefly rising above 50 percent around the two elections he won and at the very end of his term, but he otherwise spent much of his eight years in the 40s. Donald Trump is the only president during the seven decades that Gallup has been regularly tracking approval ratings who never once topped the 50 percent mark. Joe Biden floated above that mark early in his term but hasn’t seen it since.

It’s not just in terms of public support that recent presidents have been weak. This can be hard to grasp because we still live with the bromides of “the imperial presidency” — a term made famous by the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in the 1970s to describe an office drunk with power and towering over American government. We implicitly think this is still the case.

But this persistent cliché keeps us from seeing the real contours of our strange constitutional moment. Joe Biden and Donald Trump may well be the two weakest presidents since before the progressive era.

They have been weak presidents of different sorts. Mr. Biden has largely declined to set priorities for his administration and has been so desperate not to divide his party that he has been nearly paralyzed. Think of any other modern president, including Mr. Trump, and you can probably list two or three issues he particularly cared about. Can you come up with such a list for Mr. Biden? Other than the withdrawal from Afghanistan, is there any major initiative his administration has pursued because it was singularly what the president wanted to do?

Even when he has overreached in his use of administrative power — as with the legally dubious forgiveness of student loans — Mr. Biden has often acted under pressure from party activists. On many important measures in Congress, Mr. Biden’s views do not appear to have been decisive, and he has not been essential to the negotiations that led to any of the bipartisan deals he has signed.

Mr. Trump exhibited another kind of weakness. During his presidency, he dominated most news cycles and sought to operate outside the formal framework of presidential power in ways that ultimately posed real threats to the constitutional system. But within that system, where our government actually governs, he was feckless and chaotic, and largely failed to exert meaningful control even over his subordinates. His most significant achievement was in the realm of presidential power that requires the least persistent follow-through: the appointment of judges, including three Supreme Court justices, where the president’s role ends almost as soon as it begins. In other arenas, he generally couldn’t steer any one course long enough to get very far.

Astonishingly blatant insubordination was routine in Mr. Trump’s White House, and it was matched by a bipartisan tendency in Congress to regard the president’s words as devoid of meaning and his actions as always open to reversal. No one took him seriously as an executive.

The administrative state — that tangle of agencies that compose the executive branch, some formally independent and others more answerable to the White House — remains a formidable force in this era. But its growth has not always strengthened our presidents. This is most obvious in Republican administrations, as the chief executive strains to wrangle career officials and independent regulators who often want to steer a course different from his. But those same agencies operate in Democratic administrations, and even if the course they steer better suits a left-leaning president, their autonomous strength can render him institutionally weaker.

The same might be said of presidential appointees. One measure of a president’s administrative prowess is whether his midlevel political appointees can readily imagine what the president would do if he were in their jobs and act accordingly. This has been fairly easy to do under most modern presidents. But under both Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump, many appointees could be forgiven for having no idea how the president would want them to make key decisions — Mr. Trump because he was so unpredictable, and Mr. Biden because he so rarely has set clear goals.

These distinct but related forms of presidential weakness gesture toward two key elements of the job. Alexander Hamilton argued that a strong chief executive exhibits energetic decision-making and “steady administration.” Both elements are necessary, and the absence of either, Hamilton suggested, “implies a feeble execution of the government.”

Those of us who would like to see Congress reassert itself might hope for a silver lining in such presidential feebleness. But the evidence of recent Congresses suggests those hopes are misguided. The past couple of years have seen the passage of some meaningful bipartisan measures — on public health, infrastructure, gun control, manufacturing and more. But they have often revealed the contemporary Congress’s own weaknesses — the gangs of senators have often worked around rather than through the committee system and regular order — more than they have remedied them.

This should not surprise us. The president and Congress don’t have the same job, and the weakness of one does not make the other stronger. On the contrary, it often distorts the work of the other and invites more weakness in return.

When that happens, partisanship rushes in to fill the void and soon makes for a vicious cycle: Congress and the presidency increasingly incline to the same sort of work — neither legislative nor executive but more like partisan performance art — and both grow more forgetful of their core responsibilities.

This is a particular problem for our presidents because, unlike Congress’s job, the president’s role is defined by obligations he must meet. As the political scientists Joseph Bessette and Gary Schmitt have argued, the presidency is better understood as a collection of duties than an arrangement of powers, and presidential strength is often a function of living up to those responsibilities.

It is by doing the chief executive’s core work — faithful, predictable execution of statutes; steady administrative rule-making that can last beyond the next election; cleareyed prioritization and prudential action within the law in response to pressing national challenges — that a president can wield and therefore fortify the strengths of the office. Playing chief pundit and willfully blurring the line between rhetoric and action is a recipe not for influence but for haplessness.

Until our chief executives grasp that the burdens of their office are its strengths, they will remain baffled by their own debility and unable to marshal the public to their side.

ARTICLE

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/24/opinion/biden-trump-weak-presidents.htmlMY THOUGHTS

I think of presidents in the USA in era's based on a president that defined the era. In my view we are in the Ronald Reagan presidents era.

Ronald Reagan like all presidents after him has a few things in common.

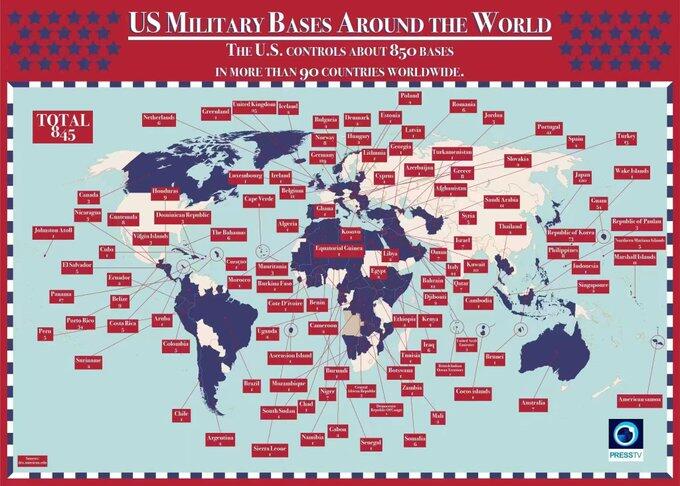

All are huge militarists, increasing military power in hundreds of percent in various forms.

All are domestic incapables, varying plans of domestic agenda that are bound to create more problems or fail in terms of leading to multiracial comradery and are not comprehensive enough for a multiracial populace that is differed not only in appearance/phenotype but differ in financial qualities/financial potencies/heritage concerning the usa and with a general negativity in inter racial relationships between themselves or in themselves.

All are media barons, they each were very successful in the presentation of potential greatness.

All are legislative obsolescences, each have dysfunctional legislative history <from woeful to nonexistent> before they became president.That explains why under the reagan presidencies the military has grown so vast. The populace of the usa has displayed ever growing dysfunction between its races. The role of media has become more important than any legislative or governing quality. Legislative quality is so low.

Putin Is Onto Us

Oct. 25, 2022

By Thomas L. Friedman

Opinion ColumnistAs the Russian Army continues to falter in Ukraine, the world is worrying that Vladimir Putin could use a tactical nuclear weapon. Maybe — but for now, I think Putin is assembling a different weapon. It’s an oil and gas bomb that he’s fusing right before our eyes and with our inadvertent help — and he could easily detonate it this winter.

If he does, it could send prices of home heating oil and gasoline into the stratosphere. The political fallout, Putin surely hopes, will divide the Western alliance and prompt many countries — including ours, where both MAGA Republicans and progressives are expressing concerns about the spiraling cost of the Ukraine conflict — to seek a dirty deal with the man in the Kremlin, pronto.

In short: Putin is now fighting a ground war to break through Ukraine’s lines and a two-front energy war to break Ukraine’s will and that of its allies. He’s trying to smash Ukraine’s electricity system to ensure a long, cold winter there while putting himself in position (in ways that I’ll explain) to drive up energy costs for all of Ukraine’s allies. And because we — America and the West — do not have an energy strategy in place to dampen the impact of Putin’s energy bomb, this is a frightening prospect.

When it comes to energy, we want five things at once that are incompatible — and Putin is onto us:

1. We want to decarbonize our economy as fast as we can to mitigate the very real dangers of climate change.

2. We want the cheapest possible gasoline and heating oil prices so we can drive our cars as fast and as much as we want — and never have to put on a sweater indoors or do anything to conserve energy.

3. We want to tell the petrodictators in Iran, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia to take a hike.

4. We want to be able to treat U.S. oil and gas companies as pariahs and dinosaurs that should pump us out of this current oil crisis and then go off in the woods and die and let solar and wind take over.

5. Oh, and we don’t want any new oil and gas pipelines or wind and solar transmission lines to spoil our backyards.

I understand why people want all five — now. I want all five! But they involve trade-offs, which too few of us want to acknowledge or debate. In an energy war like the one we’re in now, you need to be clear about your goals and priorities. As a country, and as a Western alliance, we have no ladder of priorities on energy, just competing aspirations and magical thinking that we can have it all.

If we persist in that, we are going to be in for a world of hurt if Putin drops the energy bomb that I think he’s assembling for Christmas. Here’s what I think is his strategy: It starts with getting the United States to draw down its Strategic Petroleum Reserve. It is a huge stock of crude oil stored in giant caverns that we can draw on in an emergency to offset any cutoff in our domestic production or imports. Last Wednesday, President Biden announced the release of 15 million more barrels from the reserve in December, completing a plan he laid out earlier to release a total of 180 million barrels in an effort to keep gasoline prices at the pump as low as possible — in advance of the midterm elections. (He didn’t say the last part. He didn’t need to.)

According to a report in The Washington Post, the reserve contained “405.1 million barrels as of Oct. 14. That’s about 57 percent of its maximum authorized storage capacity of 714 million barrels.”

I sympathize with the president. People were really hurting from $5- and $6-a-gallon gasoline. But using the reserve — which was designed to cushion us in the face of a sudden shut-off in domestic or global production — to shave a dime or a quarter off a gallon of gasoline before elections is a dicey business, even if the president has a plan for refilling it in the coming months.

Putin wants America to use up as much of its Strategic Petroleum Reserve cushion now — just like the way the Germans gave up on nuclear energy and he got them addicted to Russia’s cheap natural gas. Then, when Russian gas was cut off because of the Ukraine war, German homes and factories had to frantically cut back and scramble for more expensive alternatives.

Next, Putin is watching the European Union gear up for a ban on seaborne imports of crude oil from Russia, starting Dec. 5. This embargo — along with Germany and Poland’s move to stop pipeline imports — should cover roughly 90 percent of the European Union’s current oil imports from Russia.

As a recent report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., noted, “Crucially, the sanctions also ban E.U. companies from providing shipping insurance, brokering services or financing for oil exports from Russia to third countries.”

The U.S. Treasury and European Union believe that without that insurance, the number of customers for Russian oil will shrink dramatically, so they are telling the Russians that they can get the insurance for their oil tankers from the few Western insurance companies that dominate the industry only if they lower the price of their crude oil exports to a level set by the Europeans and the United States.

My sources in the oil industry tell me they seriously doubt this Western price fixing will work. Russia’s OPEC Plus partner Saudi Arabia is certainly not interested in seeing such a buyers’ price-fixing precedent set. Moreover, international oil trading is full of shady characters — does the name Marc Rich ring a bell? — who thrive on market distortions. Oil tankers carry transponders that track their locations. But tankers engaged in shady activities will turn their transponders off and reappear days after they’ve made a ship-to-ship transfer or will transfer their cargo into storage tanks somewhere in Asia for re-export, in effect laundering their Russian oil. Oil in just one very large tanker can be worth roughly $250 million, so the incentives are enormous.

Now add one more dodgy player to the mix: China. It has all kinds of long-term, fixed-price contracts to import liquefied natural gas from the Middle East at roughly $100 a barrel of oil equivalent. But because of President Xi Jinping’s crazy approach to containing Covid — in recent months some 300 million citizens have been under full or partial lockdown — China’s economy has slowed considerably, as has its gas consumption. As a result, an oil industry source tells me, China has been taking some of the L.N.G. sold to it on those fixed-price contracts for domestic use and reselling it to Europe and other gas-starved countries for $300 a barrel of oil equivalent.

Now that Xi has locked in his third term as general secretary of the Communist Party, many expect that he will ease up on his lockdowns. If China goes back to anything near its normal gas consumption and stops re-exporting its excess, the global gas market will become even more scarily tight.

Last, as I noted, Putin is trying to destroy Ukraine’s ability to generate electricity. Today more than one million Ukrainians are without power, and as one Ukrainian lawmaker tweeted last week, “Total darkness and cold are coming.”

So add all of this up and then suppose, come December, Putin announces he is halting all Russian oil and gas exports for 30 or 60 days to countries supporting Ukraine, rather than submit to the European Union’s fixing of his oil price. He could afford that for a short while. That would be Putin’s energy bomb and Christmas present to the West. In this tight market, oil could go to $200 a barrel, with a commensurate rise in the price of natural gas. We’re talking $10 to $12 a gallon at the pump in the United States.

The beauty for Putin of an energy bomb is that unlike setting off a nuclear bomb — which would unite the whole world against him — setting off an oil price bomb would divide the West from Ukraine.

Obviously, I am just guessing that this is what Putin is up to, and if the world goes into recession, it could take energy prices down with it. But we would be wise to have a real counterstrategy in place, especially because, while some in Europe have managed to stock up on natural gas for this winter, rebuilding those stocks for 2023 without Russian gas and with China returning to normal could be very costly.

If Biden wants America to be the arsenal of democracy to protect us and our democratic allies — and not leave us begging Saudi Arabia, Russia, Venezuela or Iran to produce more oil and gas — we need a robust energy arsenal as much as a military one. Because we are in an energy war! Biden needs to make a major speech, making clear that for the foreseeable future, we need more of every kind of energy we have. American oil and gas investors need to know that as long as they produce in the cleanest way possible, invest in carbon capture and ensure that any new pipelines they build will be compatible with transporting hydrogen — probably the best clean fuel coming down the road in the next decade — they have a welcome place in America’s energy future, alongside the solar, wind, hydro and other clean energy producers that Biden has heroically boosted through his climate legislation.

I know. This is not ideal. This is not where I hoped we would be in 2022. But this is where we are, and anything else really is magical thinking — and the one person who will not be fooled by it is Vladimir Putin.

ARTICLE

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/25/opinion/putin-energy-gas-prices.htmlMY THOUGHTS

The problem with Biden is he became president on his not being Schrumptf. The problem is, not being like Scrumpft means , not having your own initiative, not doing things your way against others input, not caring about opinion, not focusing on your base.

And that is a problem cause, the voting group to Biden want green energy regardless of the financial costs. They want to kill the domestic oil industry with no retort from said industry. They want countries that benefit from oil that are far more potent than the countries with faux elected officials to do as they are told when it comes to energy.

And Biden in trying to satisfy the usa populace aside his voting base can't approach the foreign lands as a bully, but can't cut them off.

In the end, Biden wanted to be president... Kamala Harris wanted to be vice president

IN AMENDMENT

An unverified image

.thumb.jpg.afc88dfee9cd2927de0c440601caac13.jpg)

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)