-

Posts

4,192 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

121

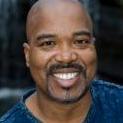

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

See the video at the following link, the transcript is beneath the following link

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/star-chasers-of-senegal/

Star Chasers of Senegal

PBS Airdate: February 8, 2023

NARRATOR: About 400-million miles from Earth, an asteroid hurtles through space. Meanwhile, scientists in West Africa train their telescopes on a distant star, anxiously hoping to catch the fleeting moment when the asteroid crosses in front of it, blocking its light.

MARC BUIE (Planetary Scientist, Southwest Research Institute): If you don’t get the data at the right second, you don’t get the data ever.

NARRATOR: They are part of a NASA mission that could revolutionize our understanding of the very beginnings of our solar system, and take the African nation of Senegal one step closer to an ambitious goal, to establish its own space agency.

MARAM KAIRE (Astronomer, Africa Initiative for Planetary and Space Sciences): Space belongs to everyone, and it is open for everyone.

NARRATOR: Star Chasers of Senegal, right now on NOVA. Senegal, on the west coast of Africa: one scientist wants to change the fortunes of his country by looking to the stars. His name is Maram Kaire.

MARAM KAIRE: Ever since I was a child, I have had a passion for astronomy. And now, I am taking part in a NASA space mission to help solve mysteries about the origins of our solar system and our planet. This is a dream come true. But I have a much more challenging mission here on Earth, to build a space agency in Senegal. I must prove to my people that science can change their lives.

NARRATOR: For Maram, that begins with helping his community to understand astronomy’s deep roots in their culture, roots that Maram is about to discover go back even further than he realized. Just off the coast of Senegal’s capital, Dakar, lies an island symbolic of a dark chapter in Africa’s past. Maram Kaire comes here to feel that history and to imagine a brighter future.

MARAM KAIRE: This is the “house of slaves,” in Gorée Island. And from this place, millions of African people were taken, by boat, across the ocean, as slaves, to America. And this is the doorway of no return. And we can imagine them just turning back and seeing this door, as maybe the last link between them and their continent. It was the last thing they have to see when they leave their land.

NARRATOR: Now, across that same ocean, a spacecraft called Lucy is getting ready to launch. Maram Kaire has been asked to help that space mission succeed. Lucy’s mission is to explore what astronomers call “Trojan asteroids,” leftovers from the time our sun and planets first formed. These ancient rocky remnants cluster in two distinct groups, trapped in Jupiter’s orbit around the sun. The spacecraft will fly by eight of them, looking for clues to better understand the birth of our solar system, about four-and-a-half-billion years ago. The asteroids are like fossils, so scientists named the mission Lucy, after a fossilized early human ancestor found in Ethiopia.

MARC BUIE: Just as Lucy teaches us about the origins of humans on Earth, Lucy the spacecraft is going to teach us about the origins of the bodies that make up our solar system that ultimately led to the Earth.

NARRATOR: But even though Lucy’s flightpath has been calculated to precisely reach its target asteroids, the probe is entering a region of space that has never been explored. It will fly past each of the target asteroids at about 15,000 miles per hour, giving scientists very little time to conduct their observations. To help guide Lucy’s approach, they’ll record events called “stellar occultations.” A stellar occultation occurs when a celestial body passes in front of a star and blocks that star’s light. At sites around the world, observers will record Lucy’s target asteroids as they eclipse stars beyond our solar system. And from the data they collect, scientists can estimate an asteroid’s precise dimensions. The occultation team is led by planetary scientist Marc Buie.

MARC BUIE: At the beginning of 2021 I noticed, “Oh, look at that. There’s one of these events, a really good one, with a nice bright star, and it goes right over Senegal.” And I’ve already worked with the people in Senegal to do two previous occultations. My first thought was I need to call Maram.

NARRATOR: Marc Buie has asked Maram Kaire to lead the mission to record the occultation of one of Lucy’s target asteroids, called Orus. His task is to coordinate a team of astronomers from Africa, Europe and the U.S. This will be his third NASA mission. In these boxes are the tools to capture an occultation: telescopes, cameras and laptops, shipped from NASA. But even the best equipment cannot guarantee success, if the sky clouds over.

MARAM KAIRE: We are crossing fingers to have good weather, also, maybe, praying just to have all the team safe and in perfect condition at the end of this mission.

NARRATOR: Maram is an internationally recognized advocate for astronomy in Africa. This occultation mission may take him one step closer to his dream of taking Senegal to space. To view the event, the team must travel three hours outside of Dakar.

MARC BUIE: I don’t get to pick which objects come up, where they go, where we need to send crews. That’s all dictated by celestial mechanics and how these things are moving around the sky.

NARRATOR: Marc needs to know the exact position and speed of Orus as it orbits, around 400-million miles from Earth, and the precise location of the distant star he predicts it will pass in front of. He estimates the event will last just 3.2 seconds. Maram and his team have only one chance to record it.

MARC BUIE: With occultations, if you don’t get the data at the right second, you don’t get the data ever.

NARRATOR: Timing is critical. By chance, Lucy is due to launch almost eight hours after the occultation.

MARAM KAIRE: And what we are doing now, with NASA, is very important, you know? By dealing with these occultation missions, we are training a young generation here in Senegal.

MARIE KORSAGA (Astrophysicist, University of Ouagadougou): Seeing this collaboration is a proof that science, especially astronomy, is collaborative and inclusive. This is very important for the development of astronomy in Africa.

SYLVAIN BOULET (Planetary Scientist, University Institute of France): Maram is a cornerstone of this event. It shows that, for 15 years Maram creates, really, a nice astronomical association in Senegal. He knows how to motivate people, and there are more and more people loving astronomy in Senegal.

NARRATOR: Maram’s passion for astronomy began with an event that shocked the world.

MARAM KAIRE: The first contact with space started with the tragedy of the space shuttle Challenger. It was the first time that I received information about space. And it was very sad to know that we lost seven astronauts with this tragedy. And I started to read books and getting out to observe the stars, constellations. I was 12, and I decided to start to build my own telescope. And this is how things began and never stopped. It’s our first training night, so each team will have the opportunity to set up his telescope.

NARRATOR: On the night of the occultation, 10 telescopes will be precisely aimed at the star that Orus will pass in front of. For just a few seconds, when Earth, asteroid and star perfectly align, Orus will block the star’s light, casting a shadow on the Earth that is the asteroid’s exact shape. By estimating the path and width of the shadow, scientists can determine where to place the telescopes. To guide the teams, Marc Buie computes a set of lines designed to cover the predicted region where the shadow will pass. Each observation team is given one of these lines, and they must find a location somewhere along it, where they can safely set up. If they can record the occultation from their vantage points, Marc will have the data he needs to determine the asteroid’s shape and size, vital information for Lucy’s flyby of Orus in 2028.

MARC BUIE: It’s one thing to say, “Put your telescope on this line,” and it’s quite another to translate they’re actually standing somewhere. The last thing you want to do is to be dealing with an angry farmer right at the time of the occultation.

NARRATOR: Every observation site must be surveyed so there are no surprises after dark.

BAIDY DEMBA DIOP (Astronomer, Association of the Promotion of Astronomy in Senegal): (Dubbed) I told them that we would be back Friday night with telescopes to observe an asteroid passing in front of a star. They said ok, no problem. They understood.

SALMA SYLLA (Ph.D. Student, Cheikh Anta Diop University): (Dubbed) You see what can happen. That is why it is important to visit the sites before we bring all of the equipment out on the night of the occultation.

MARAM KAIRE: This occultation is crucial for NASA’s Lucy mission, but it is also part of a much larger, more challenging mission, to build a space agency here in Senegal. I believe space is for everyone.

NARRATOR: For 15 years Maram has lobbied politicians to embrace these words, to convince them that Senegal’s development challenges can be addressed with space science. Many African nations have launched their own small, inexpensive satellites called Cubesats. These “eyes in the sky” have proven to be vital for communications, weather forecasting and the prediction of natural disasters. Maram believes they could be life-changing for Senegal’s large rural population, now at the mercy of unpredictable climatic events. To build and launch these satellites will take a new generation of scientists. And Maram Kaire has another goal.

MARAM KAIRE: My country is 95 percent Muslim, and many traditional Muslims are hesitant to embrace modern science. Near the end of Ramadan, our holy month devoted to prayer, contemplation and fasting, I have an opportunity to demonstrate how astronomy can help Islam. There are many people interested in learning astronomy at these events. I can show them where the crescent will appear by using astronomical calculations. I’m really nervous. It’s always the same, because we are all waiting for this moment.

NARRATOR: Time is extremely important for Muslims. Islamic law states the motion of the sun should dictate the timing of prayers. The Islamic calendar is based on the phases of the moon. The new crescent moon marks the beginning of every month and important events like Ramadan. Maram’s passion for modern astronomy inspires many Senegalese people, but Muslim authorities here only accept crescent moon sightings observed with the naked eye.

MARAM KAIRE: The Islamic tradition is to observe the moon using the naked eyes, it comes from a recommendation of the prophet. This can cause major confusion. If the crescent is not seen here tonight, because it is too thin or the skies are cloudy, the end of Ramadan will be delayed for a day. But what if it is sighted somewhere else in Senegal, where there are no clouds. When should Ramadan end? This is a centuries old dilemma that could be easily overcome with modern science.

NARRATOR: Tonight, in a compromise, the committee of imams responsible for calling an end to Ramadan have given Maram permission to use binoculars.

MARAM KAIRE: It’s just wonderful, because we were not expecting to get it, because the crescent was very, very thin. And, fortunately, we have the opportunity to see it. And maybe we will also have other information from the country. So, we have informed the national committee that the crescent was sighted here in Dakar. They have the final word to decide that the celebration will be tomorrow.

NARRATOR: Imam Diene of the National Commission for Consultation on the Lunar Crescent declares that Ramadan has come to an end.

MARAM KAIRE: Everyone is celebrating the end of fasting. I have been invited to be part of a three-hour discussion about science and Islam at our national broadcaster, R.T.S. Well, I don’t think that astronomers are celebrities. I’m not just feeling like a star or, maybe people really appreciate the kind of information we are sharing with them about astronomy, because practicing their religion depends on this kind of information.

NARRATOR: Tonight, Maram has the opportunity to talk astronomy with Imam Diene who has just called an end to the fast. In front of an audience of millions of Muslims, the Imam agrees modern science may well be the most accurate way to sight the crescent. Maram sees this as a major win.

MARAM KAIRE: To see this important person saying that it is possible now to use astronomical data is an important step in what we are doing to find a solution. Eid al-Fitr marks the end of the fast. We give thanks with a special morning prayer. Prayer is at the heart of Islam.

NARRATOR: The type of Islam practiced in Senegal is Sufism. Maram belongs to the Mouride Sufi Brotherhood, which is centered in his ancestral home, the holy city of Touba.

MARAM KAIRE: I am drawn here today by a very unusual invitation. A family of Muslim scholars would like to demonstrate their astronomical practices to me.

NARRATOR: Maram is about to discover something that will profoundly change the way he perceives astronomy in his country: an enclave of scientists who strive to perfect the measurement of time, in the service of Islam.

CHEIKHOUNA BOUSSO (Islamic Scholar, Islamic Institute of Guédé Bousso, Touba): (Dubbed) When you are interested in astronomy, you will become passionate about the universe. You will become a fan of observing what happens in space.

MARAM KAIRE: I am here to learn about the work of Cheikh Mbacké Bousso, a highly respected astronomer who lived around the turn of the 20th century. The Bousso family wish to show me a sundial which they have built in the courtyard of their mosque. It’s based on one of Cheick Mbacké Bousso’s designs. They still use it every day to find the exact prayer times here in Touba.

NARRATOR: Because the official time on a watch is not accurate enough for their needs. Official time is tied to the world’s 24 time zones and is uniform across a region, sometimes even an entire country. But there’s another type of time, true solar time, which is tied to the sun’s position in the sky at a specific location. Even travelling a short distance east or west, there’s a time difference. Only true solar times gives Muslims the accuracy they need to pray on time, wherever they are. The best way to find true solar time is to measure the sun’s shadow as it changes throughout the day. Many of us have now lost the connection between time and what happens in the sky, but not the Bousso family.

MARAM KAIRE: They are not just trying to use time like we use it in modern astronomy, but they need for a precise, accurate local time, based on the position of the sun. All the life of the Muslim are depending on this kind of information for doing things at the right moment. To build an accurate sundial, Cheick Mbacké Bousso needed to understand basic astronomy, and he needed to mark the trajectory, position and length of the sun’s shadow hour after hour.

CHEIKHOUNA BOUSSO: (Dubbed) What he used to do, every morning for 33 years, facing east with paper and ink, was to write down the times of sunrise and sunset in a notebook.

NARRATOR: And using the data collected from his observations, Cheikh Mbacké Bousso calculated the Qibla, the direction to Mecca. The Great Mosque of Touba was built to his specifications. It’s almost noon, solar time. At the precise moment the sun’s shadow is at its shortest, it will be 12 p.m. Midday is the most accurate reference point throughout the year. The muezzin sets his watch by the shadow, continuing a long tradition of finding time.

MARAM KAIRE: How did Cheikh Mbacké Bousso come to learn the basic astronomy he needed for his tasks? Cheikhouna Bousso tells me he consulted centuries old Islamic astronomy books, written in Arabic. It comes as a surprise to me that this family of Muslim scholars still practice astronomy developed in medieval times. They tell me they would like to learn about modern astronomy. We have taken different paths, but when we look to the skies, we ask the same question. Where is our place in this universe? They watch the daily movements of the sun, moon and stars to perfect their lives on Earth. I watch for the blink of a star lightyears away, to help NASA’s Lucy mission reach asteroids that may unlock the secrets of our solar system and, ultimately, our own planet.

NARRATOR: Maram thought he was bringing astronomy to Senegal. The Bousso family have shown him it’s already here. Maram has many questions. From where did Cheikh Mbacké Bousso get his books? How did other Islamic astronomers advance their knowledge of celestial events? Istanbul was the center of the powerful Ottoman Empire and the hub for all Islamic sciences, from the 15th century right up until the 1800s. Great scholars gravitated to this place to live and work. With them they brought astronomy books written in Arabic, like the ones Cheikh Mbacké Bousso may have studied. Maram has come to Istanbul to meet Taha Yasin Arslan, an expert on the history of astronomy in the Islamic world.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN (Historian of Science, Istanbul Medeniyet University): Starting from ninth century, scholars in the Islamic world accumulated knowledge from Greeks, Persians and Indians, and, using Arabic, created new scientific knowledge. And that knowledge could be used, without changing, for a thousand years, all around the Islamic world. I study astronomy in the Islamic world using astronomical instruments and timekeeping. The main reason I make these instruments is to understand the mindset of the people who were actually using or making them in the medieval times. I learnt and I understood that science in the Islamic world was not something to be left behind, because astronomy represent all the developments in mathematical sciences, in geometry, in geography, in trigonometrical calculations. It is a preparation for the modern science to build upon.

NARRATOR: Taha has invited Maram to view rare books on Islamic astronomy, written centuries ago. These may be the type of books Cheikh Mbacké Bousso had in his library.

MARAM KAIRE: Hi, Mr. Taha.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: Hello.

MARAM KAIRE: Nice to meet you.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: Very nice to meet you, too. Welcome to Istanbul.

MARAM KAIRE: Thank you. You have a very nice city.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: Süleymaniye Library, in Istanbul, contains 90,000 manuscripts. And this is the largest Islamic collection in the world. One can find any book in any branches of science. For most of the scholars in the Islamic world, there is at least one copy of their book in this library. So, we have a special treat here, and the library allowed us to have this magnificent manuscript. And it is by Jaghmini who is a 13th, 14th century astronomer. The importance of this book is it is disseminated all around the Islamic world. When you have any kind of information about cosmology, it will always be related to this book. Oh, yes. That’s one of the things. This is showing the eclipses. Absolutely. This is the sun, this is the earth and this is the moon.

MARAM KAIRE: This is what we call now “basic” astronomy. So, I think that for this time it’s very impressive to have to this kind of accuracy.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: I like this a lot, because in some of the pages you see so many comments there. And these are specifically made by people who are studying this and not always for astronomers. That’s the key, because science is never remaining in some sort of a elite group of people.

NARRATOR: But there are also books that only astronomers would consult. This one has instructions to make one of Islamic science’s most important and complex astronomical instruments, the astrolabe.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: As a person who makes astrolabes, I actually use this book and the calculations in this book in my own productions, as well.

NARRATOR: An astrolabe has many uses, from identifying stars to finding daily time. It may have been developed by the Greeks, but it reached its zenith in the hands of Islamic scientists. They wanted to make better, more accurate instruments to calculate time.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: This is an Islamic astrolabe. This instrument is actually a mechanical computer. What you see here is the projection of the sky for a specific latitude. This is for Istanbul.

NARRATOR: Etched on the base plate is the horizon line, precise altitude circles marking the sun’s height above the horizon, and the meridian, showing midday and midnight. On top of the base plate is a moveable plate, showing stars and constellations, and a ring that represents the apparent movement of the sun throughout the year. It’s labelled with dates.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: It starts with one single observation. And we will actually try to maintain the position of this piece, exactly aligning with the sun. I think it’s now aligned. This is a perfect alignment. And we just read the altitude from here to here. It’s 54 degrees.

NARRATOR: That means the sun is 54 degrees above the horizon. The user now turns the astrolabe over to find the 54 degrees circle on the bottom plate. Next step, find and mark the date; it’s etched on the ring that represents the sun’s path. Then rotate the plate until the date aligns with the altitude mark. If you take a piece of string from the center of the astrolabe through the aligned points, you can read the time from the rim. The line is like the hand of a clock. It’s four minutes past two in the afternoon.

TAHA YASIN ARSLAN: Once we reach that, we can calculate any time. That is not a simple-to-use instrument but accurate enough for all timekeeping applications. For the Islamic world, time is much more important than any other religion, society or culture, because their lives are depending on the timekeeping for daily practices of Islam or yearly practices of Islam or even lifetime practices of Islam.

NARRATOR: In Istanbul, Maram has learned how medieval scientists used astronomy in the service of Islam. This knowledge is still alive in Senegal today. But was there astronomy in Senegal before Islam? Maram would like to know. He may soon discover that his country’s connection with the stars reaches much further back in time than he ever realized. Clues can be found along a vast stretch of the River Gambia, where more than a thousand stone circles have been constructed. They were built over thousands of years, right up until the 16th century. Many human remains and artifacts have been excavated at the sites. Scientific research has mainly focused on the burial practices and rituals of the builders. That is about to change. Maram wants to look at them through the eyes of an astronomer.

MARAM KAIRE: The first time I heard about these places, I was just asking myself if we can have the same configuration, the same set up between the sample of Stonehenge and these stone circles here in Senegambia.

NARRATOR: They are one of the largest concentrations of megaliths so far recorded in the world. But the stone circles are not well known outside of Senegal, and some of them are difficult to find. There are not many signs showing directions to the sites, and the roads and tracks are like a maze. But the local villagers know exactly where the stone circles are located. Maram is joined by archaeologist Aimé Kantoussan and planetary scientist Marc Buie, who is also curious about humanity’s ancient connections to astronomy. They will look for evidence of astronomical alignments at the sites.

MARAM KAIRE: You have some megaliths, there on the right.

MARC BUIE: The quest that Maram laid in front of me was to somehow show a different and new aspect to these stone circles than had ever before been realized and, specifically, to say, “Is there a direct connection to astronomical phenomena?”

NARRATOR: They will begin their survey at Sine Ngayene, the largest stone circle site. It is inscribed on the World Heritage list as a place of universal value. Neither the local people nor visiting archaeologists know who built these circles.

AIMÉ KANTOUSSAN (Archaeologist, Museum of Black Civilizations): There is no connection between the people who build these kind of sites and the people who are living here right now. It’s just like they built this kind of site, used them, and they just disappeared.

MARAM KAIRE: Aimé tells us that the circles have marker stones facing east. There is a solitary stone that catches my attention. I think it’s important, because there are other stones nearby that may align with it.

MARC BUIE: You are saying this has a special orientation. And I’m measuring this angle here to the second stone, which, according to my calculations, is where the sun sets at the beginning of the summer, at the solstice. So, when I look this direction, I confirm the angle 124 degrees to that rock is where the sun would rise at the beginning of winter. So, when I look this direction, this angle is very, very close to the equinox for the beginning of spring and fall.

NARRATOR: The people who placed these stones would have observed how the locations of sunrise and sunset varied over the year. When the sun reached its northernmost point, it was the longest day, the summer solstice; at its southernmost point, the shortest day, the winter solstice. And when the sun rose directly east, the days and nights were equal in length, the equinoxes. By aligning stones to these points, the builders would have been able to track the seasons. And Marc and Maram discover that these stones may demonstrate additional astronomical knowledge.

MARC BUIE: That small stone there is exactly north of this stone.

MARAM KAIRE: That’s crazy. This one?

MARC BUIE: Yes.

MARAM KAIRE: Let me check from here. Yeah, I’m facing to the south.

MARC BUIE: So, this is a great big compass on the ground.

MARAM KAIRE: Wow. I’m smiling just because it’s incredible. Wow.

NARRATOR: There were several ways the stone circle builders could have found north. One way was by looking at the patterns and the motions of the stars.

MARC BUIE: Right now, you would use Polaris, but in the past, Polaris won’t be in exactly the right spot, but the stars will still trace out a circle, if you’re paying attention. Makes me wonder which came first, these stones or the circles? So, I’m left with the question, why did they care so much about this? What did they use it for? What was their intent in setting this up? Is it just to do the metrology for all the other stone circles, or was it just exploring the universe?

NARRATOR: And, they find the same alignments at another stone circle site, called Wanar.

MARC BUIE: So, is this what you were hoping to find?

MARAM KAIRE: Well, exactly what we were searching for. And what is amazing is to have the same information from the Sine Ngayene site and the Wanar site. And it’s incredible.

MARC BUIE: I think that the historical record for human civilization shows a connection to astronomy from the very beginning, understanding the stars, sunrise, sunset, the phases of the moon. All of that work culminates in being able to fly a mission like Lucy that has to fly through space, launched on a rocket, and end up in the right place to study the solar system.

NARRATOR: At Cape Canaveral the Lucy mission is entering its countdown to launch, while in Senegal, Maram and his team undertake final preparations before the occultation.

MARAM KAIRE: We are now loading crates with telescopes on the vehicles, and just after that, we are moving to the observation sites to watch the occultation.

MARAM KAIRE: Tout est parfait. On est à l’heure.

SCIENTIST: On y va. C’est bon.

MARAM KAIRE: Allez, bonne chance! Bye!

NARRATOR: For the last three nights, the teams have practiced setting up and aiming their telescopes at the star Orus will pass in front of. At 1:55 tomorrow morning, they will know if their preparations have been enough.

MARIE KORSAGA: To be honest, I feel a bit stressed, but I am confident.

SYLVAIN BOULE: I think that we are ready with the computer, with the telescope, but we hope that the sky will be the same during the next two hours.

MARAM KAIRE: I’m nervous. I can’t hide it. I’m a little bit nervous.

NARRATOR: The telescope is aimed at the distant star. The team needs to capture the crucial moments when the asteroid blocks the star’s light. The countdown begins.

SYLVAIN BOULE: (countdown in French) Please no more floodlights. Dix, neuf, huit, sept, six, cinq, quatre, trois, deux, un. Yes, man, we got it.

MARAM KAIRE: We got an occultation! Fantastic! Can I dance right now?

MARIE KORSAGA: I was very excited when I saw this occultation.

SYLVAIN BOULE: It’s great! You see, maybe, my eyes shining. It’s just a great moment.

MARAM KAIRE: We have the sky very good and very clear to have our occultation, and just five minutes after, the sky is getting cloudy. So, I’m so happy. And it’s fantastic.

NARRATOR: All of the data collected by the teams is sent to Marc Buie who is waiting at Cape Canaveral for Lucy to launch.

MARC BUIE: In the hours leading up to the Lucy launch, I was getting early reports from Senegal that it was successful, and a picture was emerging of Orus.

NARRATOR: Marc determines the asteroid is 31 miles high and 42 miles across. It’s elliptical in shape and with some puzzling surface features; an outstanding result, which will help NASA plan Lucy’s future encounter with Orus.

FEMALE NASA PRESENTER LIVE (NASA Lucy Live Launch Coverage/Film Clip): Lucy in the sky with asteroids. in L-minus-34 minutes, this Atlas V rocket will send Lucy on the first ever space mission to study the Trojan asteroids, which share Jupiter’s orbit around the sun.

MALE NASA PRESENTER LIVE (NASA Lucy Live Launch Coverage/Film Clip): Named after the Lucy fossil, the spacecraft will visit eight asteroids over 12 years, as we seek to uncover the mysteries of our solar system’s formation.

MARC BUIE: The NASA Lucy mission is almost certainly going to be a game changer. What games is it going to change? Probably the origin of the solar system, if that weren’t a big enough topic.

NARRATOR: The Lucy mission has taken Maram’s dream to build a space agency one step closer to reality. The successful NASA collaboration has been praised by Senegal’s president. And Maram has found a deep and rich history of astronomy in his country, ancient connections to space he never dreamed existed, that show how humans have always looked to the skies for answers about our lives on Earth.

MARAM KAIRE: I need to know my place inside this universe, and watching the stars and using astronomy is just giving me a sort of answer. I started very young, and I keep on learning and searching. And I think that it’s the most wonderful way to live my life.

CAPTION: LUCY IS SCHEDULED TO REACH TARGET ASTEROID ORUS IN 2028.

NARRATOR: The International Astronomical Union have recently honored Maram: orbiting the sun, in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, is “Asteroid 35462 Maramkaire.”

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)