-

Posts

4,192 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

121

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

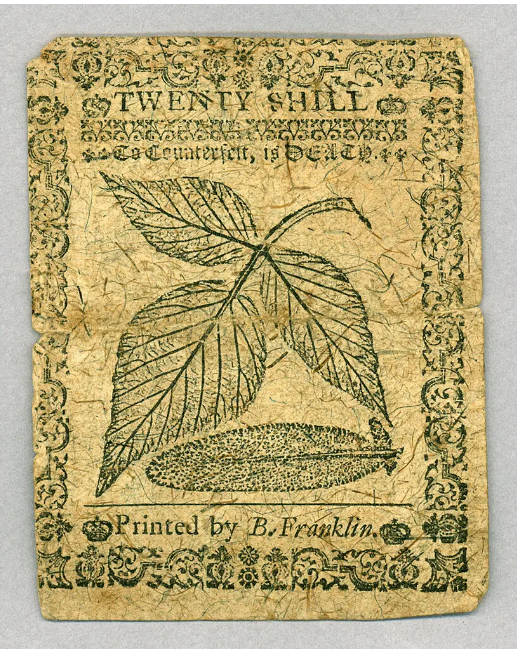

In 1731, Benjamin Franklin won the contract to print £40,000 for the colony of Pennsylvania, producing a stream of baroque, often beautiful money.Credit...Department of Special Collections, Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame

What Benjamin Franklin Learned While Fighting Counterfeiters

Long before there were Benjamins in circulation, the founding father was all about experimenting with printing techniques as he worked on securing colonial printed currency.

By Veronique Greenwood

July 17, 2023

When Benjamin Franklin moved to Philadelphia in 1723, he got to witness the beginning of a risky new experiment: Pennsylvania had just begun printing words on paper and calling it money.

The first American paper money had hit the market in 1690. Metal coins never stayed in the 13 colonies long, flowing in a ceaseless stream to England and elsewhere, as payment for imported goods. Several colonies began printing bits of paper to stand in for coins, stating that within a certain time period, they could be used locally as currency. The system worked, but haltingly, the colonies soon discovered. Print too many bills, and the money became worthless. And counterfeiters often found the bills easy to copy, devaluing the real stuff with a flood of fakes.

Franklin, who started his career as a printer, was an inveterate inventor who would also create the lightning rod and bifocals, found paper money fascinating. In 1731, he won the contract to print £40,000 for the colony of Pennsylvania, and he applied his penchant for innovation to currency.

During his printing career, Franklin produced a stream of baroque, often beautiful money. He created a copper plate of a sage leaf to print on money to foil counterfeiters: The intricate pattern of veins could not easily be imitated. He influenced a number of other printers and experimented with producing new paper and concocting inks.

Now, in a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of physicists has revealed new details about the composition of the ink and paper that Franklin used, raising questions about which of his innovations were intended as defenses against counterfeiting and which were simply experiments with new printing techniques.

The study draws on more than 600 artifacts held by the University of Notre Dame, said Khachatur Manukyan, a physicist at that institution and an author of the new paper. He and his colleagues looked at 18th-century American currency using Raman spectroscopy, which uses a laser beam to identify specific substances like silicon or lead based on their vibration. They also used a variety of microscopy techniques to examine the paper on which the money was printed.

Franklin influenced a number of other printers and experimented with producing new paper and concocting inks.Credit...Department of Special Collections, Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame

Some of what they observed confirms what historians have long known: Franklin’s paper money contains flecks of mica, also known as muscovite or isinglass. These shiny patches were most likely an attempt to combat counterfeiters, who would not have had access to this special paper, said Jessica Linker, a professor of American history at Northeastern University who studies paper money of this era and was not involved in the study. Of course, that didn’t stop them from trying.

“They come up with very good counterfeits, with mica pasted to the surface,” Dr. Linker said.

In the new study, the researchers found that the mica in bills for different colonies seems to have come from the same geological source, suggesting that a single mill produced the paper. The Philadelphia area is notable for its schist, a flaky mineral that contains mica; it’s possible that Franklin or printers and papermakers associated with him collected the substance used in their paper locally, Dr. Manukyan said.

When they examined the black ink on some of the bills, however, the scientists were surprised to find that it appeared to contain graphite. For most printing jobs, Franklin tended to use black ink made from burned vegetable oils, known as lampblack, said James Green, librarian emeritus of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Graphite would have been hard to find, he suspects.

“So Franklin’s use of graphite in money printing is very surprising, and his use on bills printed as early as 1734 is even more surprising,” Mr. Green said in an email.

Could using graphite ink have been a way to differentiate real money from fakes? Differences in color between graphite and lampblack are likely to have been subtle enough to make that a difficult task, Mr. Green said. Instead, we may be looking at another example of Franklin’s creativity.

“It suggests to me that almost from the start he was using his money printing contracts as an opportunity to experiment with an array of new printing techniques,” he said.

To understand more clearly Franklin’s intent, more analyses of printed documents from the era would be helpful, said Joseph Adelman, a professor of history at Framingham State University in Massachusetts.

“The comparison I would most like to see would be Franklin’s other publications,” Dr. Adelman said. “To really test this theory — does Franklin have this separate store of ink?”

In future research, Dr. Manukyan hopes to collaborate with scholars who have access to larger collections of early American paper money. These techniques can be quite valuable in the study of history, Dr. Linker said, if scientists and historians can work together to identify the best questions to answer.

“I have questions about a whole bunch of inks. There’s a really weird green on some of the New Jersey bills,” she said, referring to money printed by a Franklin contemporary. “I would love to know what that green ink was made of.”

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/17/science/benjamin-franklin-counterfeit-currency.html

A prehistoric model at the Crystal Palace Park in London gets a sprucing up in 1930. Credit...Fox Photos/Getty Images

A Victorian Dinosaur Park Finds Its Way in the 21st Century

Statues of extinct animals peek out from the trees, delighting onlookers in this London park. But don’t expect them to be scientifically accurate.

By Claire Moses

Reporting among the dinosaurs in Crystal Palace Park in London

July 14, 2023

Imagine: It’s 1854. The concept of evolution won’t be introduced for another five years or so. The word dinosaur is only about a decade old. There are no David Attenborough documentaries teaching you about extinct animals.

Now imagine yourself as a resident of Victorian London, walking into Crystal Palace Park in the southeastern part of the city. There you encounter dozens of three-dimensional dinosaurs and ancient mammals you could have never imagined, made of clay, brick and other available building materials. They are arranged in small groups, poking out from behind trees and bushes, some of them towering over their human visitors out for an afternoon stroll.

Except you don’t have to imagine too hard, because those statues are still there, some 170 years later. They’re a little worse for wear and are no longer considered scientifically accurate. But they delight visitors all the same. And this month, thanks to conservators, scientists and a group called the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, their Paleolithic picnic party grew a little, with the addition of a new statue — well, a recreation of an old statue — to replace one that disappeared in the 1960s.

The park in 1911.Credit...Getty Images

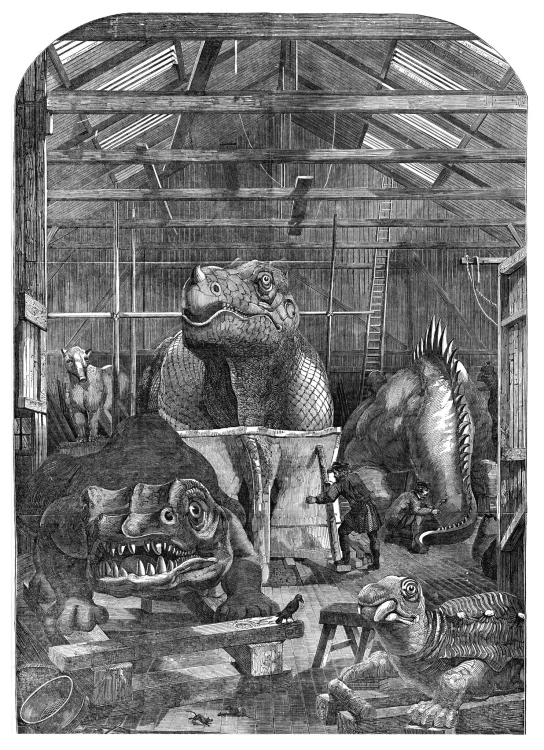

The statues, built by the 19th century artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, are part of a reconstructed geological walk through time, starting 260 million years ago. They were the first of their kind, much to the admiration of the public at the time.

“It was educational for the Victorians,” said Adrian Lister, a paleobiologist at the Natural History Museum in London. “It was revolutionary.”

The sculptures by Mr. Hawkins, who was one of the best-known natural history sculptors at the time, were supposed to educate and entertain visitors near the Crystal Palace, an exhibition space that had been built for London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. After the exhibition, that palace moved to the area to which it gives its name today. (The statues have outlived the actual palace, which burned down in 1936.)

An illustration of the “Extinct Animals” model room at Crystal Palace in 1853. It shows models of dinosaurs being prepared for a display organized by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins.Credit...Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

The statues popularized science, bringing the idea of extinction and changing environments to regular people, not just the upper classes, said Ellinor Michel, an evolutionary biologist and the chair of Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. “This was the birthplace of large-scale ‘edu-tainment,’” said Ms. Michel, who also lives nearby.

The statues do not reflect the extinct animals based on what we know today. Within decades of their construction they were out of date, Ms. Michel said, because of new scientific discoveries.

But accuracy isn’t the point, Ms. Michel said. “Science moves and science self improves,” she said.

Of the 38 original statues, 30 remain, and they show every bit of their almost 170 years.

The statues are made from whatever materials were available at the time, and as a result, are plagued by issues like rusting iron. While they’ve been maintained over the years, some look weathered, and at least one of them is missing a head.

“They weren’t built to last that long,” said Simon Buteux of Historic England, an organization that advises the government on England’s heritage. “We’ve got a huge problem of conserving them.”

What’s important to maintain, Mr. Buteux said, is the original feeling of how revolutionary these statues were in the 19th century.

“It was fresh, it was new, it was cutting edge,” he added. “That’s what we want to capture.”

One of the few known images of Palaeotherium magnum, from 1958.Credit...Crystal Palace Foundation

No one knows quite what happened to the original Palaeotherium magnum, which disappeared from the park in the 1960s. An herbivore that was loosely related to horses, the statue looked something like a horse with stumpy snout.

Seven other statues are also missing. The circumstances surrounding most of the disappearances are “giant mysteries,” Ms. Michel said.

Bob Nicholls, an artist who focuses on prehistoric animals, proposed bringing back the Palaeotherium magnum to the park. The Friends of Crystal Palace Park Dinosaurs then secured funding that helped make his recreated Palaeotherium magnum a reality. The new statue was installed in the park in early July.

To recreate what Mr. Hawkins imagined the herbivore might have looked like, Mr. Nicholls turned to the few available photographs of it from the 1950s and ’60s.

It took him about six weeks to build the new statue, which is hollow inside and made of fiberglass, a durable material. He’s happy with how it turned out, he said: “It’s got a silly face.”

“The new sculpture draws attention to the importance of the site in the history of science,” Mr. Lister, the paleobiologist, said.

About half a million people visit the statues annually, according to the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. And they continue to inspire awe, with parents taking pictures of their children in front of them and lingering by the large statues.

On a recent sunny afternoon, Jenny Steel, a local resident who walks through the park multiple times a week, was on her way to admire the newest addition. “They are quite larger than life,” she said.

Just a bit further along the walk, Ian Baxter, who has lived in the area for 50 years, was sitting on a rock near the statues with his poodle, Rory. Back when he was a teenager, he said, he used to climb into the hollow structures. Today, he looks at them from the other side. “I like the dinosaurs,” he said. “Of course I do.”

Another local resident, Gabriel Birch, said he visits the park at least once a month.

“We come here for the dinosaurs,” he said. “My three-year-old thinks they’re real.”

Claire Moses is a reporter for the Express desk in London.

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/14/world/europe/crystal-palace-dinosaurs-london.html

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)