-

Posts

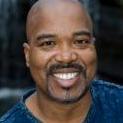

4,189 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

121

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

A Tradition Going Strong: Brides Who Take Their Husbands’ Names

The women least likely to do so tend to be liberal or highly educated or Hispanic, new data shows.By Claire Cain Miller

Sept. 12, 2023When Irene Evran, formerly Irene Yuan, married Colin Evran three years ago — in a civil ceremony on Zoom during the depths of the pandemic — the decision to take his name felt like a natural one.

Her mother had kept her maiden name, as is traditional in China, where they are from. But Ms. Evran thought it would be easier to share a name with her husband and their future children. It was important to him, she said, and she liked how his name sounded with hers.

“It wasn’t a difficult decision,” said Ms. Evran, 35, of San Francisco. “There may be deep-rooted traditional influence, but it felt pretty simple and straightforward.”

The bridal tradition of taking a husband’s last name remains strong. Among women in opposite-sex marriages in the United States, four in five changed their names, according to a new survey by Pew Research Center.

Fourteen percent kept their last names, the survey found. The youngest women were most likely to have done so: A quarter of respondents who were 18 to 34 kept their names.

Hyphenated last names were less common — about 5 percent of couples across age groups took that approach — and less than 1 percent said they did something different, like creating a new last name. Among men in opposite-sex marriages, 5 percent took their wife’s name.

Marital naming has become yet another way in which Americans’ lives diverge along lines of politics and education. Among conservative Republican women, 90 percent took their husbands’ name, compared with 66 percent of liberal Democrats, Pew found. Eighty-three percent of women without a college degree changed their names, while 68 percent of those with a postgraduate degree did.

The women who keep their names are likely to be older when they marry, research shows, and to have established careers and high incomes. They have invested in “making their name” professionally, said Claudia Goldin, an economist studying gender at Harvard who co-wrote a paper with that title with Maria Shim.

People are marrying later than in previous generations, and highly educated people are more likely to marry. That would suggest that more women would be keeping their names, said Sharon Sassler, a sociologist at Cornell who studies young people’s transitions into adulthood.

“However, we adjust to the gender norms of our time, which, ‘Barbie’ notwithstanding, is not a very pro-feminist time period,” she said.

Also, she said, weddings are a time of highly gendered traditions: “I don’t think a lot of women want to talk about, ‘How is marriage a patriarchal institution?’ especially as they’re making the decision to enter into marriage.”

Some younger women say the decision has become more practical than political — they find it easier to have the same name as their future children, and to simplify dinner reservations or utility bills.

Immigrants to the United States and Black and Hispanic women are less likely to take a spouse’s name. Eighty-six percent of white women did, Pew found, compared with 73 percent of Black women and 60 percent of Hispanic women. (It is customary to keep one’s name in many Spanish-speaking countries.) There were not enough Asian American women in the sample to analyze.

When Olivia Castor, 28, a corporate lawyer in Chicago, married three weeks ago, she decided to take both routes. She is in the process of legally changing her last name to that of her husband, Austin McNair, but she will continue to use Castor professionally.

Left- Austin McNair and Olivia Castor at their August wedding in Chicago. She is changing her name to his, but will continue to use Castor professionally.Credit...Candace Sims Photography

Right-Her parents, Aliette and Osner Castor, at their 1990 wedding, after they immigrated from Haiti. She took his name, as is traditional in both Haiti and the United States.Credit...via Olivia Castor

She is the daughter of Haitian immigrants, and wanted to keep her Haitian last name and honor her family’s role in her education and career success.

“It meant a lot to me to have that family name, a legacy of accomplishment in the U.S., and I didn’t want to let go of that,” she said. “But I also wanted to embrace the new life and family I’m starting with my husband.”

Pew’s findings, from a poll of 2,740 married people, conducted in April, are consistent with other data showing that roughly 20 percent of women have kept their names since the practice took hold in the 1970s. But it’s hard to know how it’s changed over time because there has been so little research on it. (It’s seen as a “women’s issue,” and thus “not seen as valuable by people who fund research,” said Laurie Scheuble, a professor emeritus at Penn State who co-wrote a paper on name changing in 2012.)

Pew’s survey did not include enough same-sex couples to draw conclusions. Some said that because of the lack of a tradition, same-sex couples felt freer in their choice.

For Rosemary and Christena Kalonaros-Pyle — who work in marketing in New York and celebrated their July marriage with 115 family members and friends in Mexico — the solution was to hyphenate.

“We wanted to both have the same last name as our children would have, just because legally it’s a lot more prudent, especially as a same-sex couple, where in certain states and certain countries things are recognized differently,” Rosemary Kalonaros-Pyle said.

They also wanted to keep her Greek last name — and honor the last name of Christena Kalonaros-Pyle’s father, who died before her wife could meet him.

“It was a little bit of legal logistics,” she said, “and a little bit of emotions.”

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/12/upshot/maiden-names-change.html

What last name did you give your children? Some families break with tradition when it comes to their children’s last names. Please share your story. (The Times won’t quote you or refer to your submission in a story before talking to you first.) Email the reporter on this story, Claire Cain Miller.

mailto:ccm@nytimes.com?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=ArticleMY THOUGHTS

Well, beyond the limited scope of the statistical graphic, it displays with the small count of women, heterosexual women, a simple truth. Three ways: Black women are the highest in sharing a last name. Mestizo+mulatto women are highest in keeping their own name. White women are highest in changing to thier husbands name. That shows three different approaches to males. They are all women but they are not the same. In AALBC forums, many have suggested that black men are being emasculated but based on this simple graphic i argue it is mestizo or mulatto men who are being emasculated. But said people in AALBC or media folk who chime a similar tool say nothing. To me the answer is far simpler, couples need to talk to each other and know each other's honest opinions. The problem is many people don't communicate in the relationships they are in. they perform sexual or financial acts or perform public displays but rarely talk to each other in the way a relationship needs.

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)