-

Posts

2,425 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

91

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Blogs

Events

Everything posted by richardmurray

-

Title: Sea Cloak

Artist: GDBee < https://gdbee.store/ >

Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2050&type=status

GDBee Post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=gdbee&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=or&sortby=newest

-

Title: Firefly, CHicory, nunchuku- weapons fairy

Artist: GDBee < https://gdbee.store/ >

Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2037&type=status

GDBee Post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?&q=gdbee&type=core_statuses_status&quick=1&author=richardmurray&search_and_or=or&sortby=newest

-

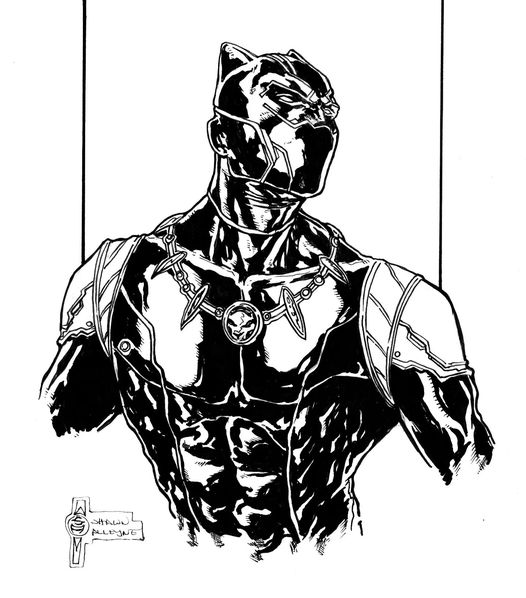

Title: Black Panther Sketch

Artist: shawn alleyne < Pyroglyphics Studio > OR < https://www.deviantart.com/pyroglyphics1 >

Prior post

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2036&type=status

Shawn Alleyne post

https://aalbc.com/tc/search/?q=shawn&quick=1&type=core_statuses_status&updated_after=any&sortby=newest

-

HISTORY | SEPTEMBER 2022Was King Arthur a Real Person?

The story of Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table has captivated us for a thousand years. But is there any truth behind the tales?

By Joshua Hammer https://www.simonandschuster.com/authors/Joshua-Hammer/19043478Photographs by Jooney Woodward https://jooneywoodward.co.uk/information/

A cold, wind-driven rain soaks through my parka as I walk across a narrow foot-bridge that links the Cornwall mainland in southwest England to a rocky promontory overlooking the Bristol Channel. Far below this cantilevered span, waves crash against the cliffs and swirl inside a grotto known as Merlin’s Cave. Win Scutt, a burly, amiable archaeologist from nearby Plymouth, opens a gate and leads me down a path to the ruins of a medieval castle. Its fragmentary walls mark the lair where Richard, the 13th-century Earl of Cornwall and the brother of King Henry III, is said to have gathered with his followers to feast on mutton and ale and pay homage to a monarch who may never have existed: King Arthur.

The figure of Arthur first appeared in Welsh poetry in the late sixth and early seventh centuries, a hero who was said to lead the Britons in battle against Saxon invaders. But it wasn’t until the 12th century that he was first tied to this dramatic headland, known as Tintagel. In the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, which was written in 1136 and purported to trace Britain’s history back to its supposed founding by Trojan exiles, an almost certainly fictitious sixth-century king named Uther Pendragon sleeps with the beguiling Ygerna, the wife of a local duke, at her castle in Tintagel, after the magician Merlin turns Pendragon into a likeness of her husband. “That night she conceived Arthur, the most famous of men, who subsequently won great renown by his outstanding bravery,” Geoffrey wrote.

Scholars have universally dismissed Geoffrey’s text as a pseudo-history, woven from ancient Welsh folk tales and his febrile imagination. Still, many people at the time believed the story, and Richard, Earl of Cornwall, was so convinced Arthur was real that, in May 1233, he traded three prime estates for this treeless headland, which is separated from the mainland by an isthmus, and built a castle on it. “It had no function,” Scutt says, as he leads me through the stone ruins of the castle’s great hall. “It’s in a remote part of Cornwall that had no use to him. But he wanted to anchor his position in legend and history. He was the Earl of Cornwall—but he was also the successor of Arthur.”

King Arthur has never relinquished his hold on the imagination. Writers in Geoffrey’s wake added their own flourishes—the magical sword Excalibur, the Knights of the Round Table, Arthur’s romantic triangle with Queen Guinevere and Sir Lancelot, and Arthur’s mortal wound at the Battle of Camlann. Arthurian tales of courtly love, magic and martial bravery have been told and retold in countless versions over the centuries, from the earliest eulogistic stanzas in Welsh poetry to T.H. White’s 1958 novel The Once and Future King, from Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th-century Le Morte d’Arthur to the 2021 film The Green Knight, starring Dev Patel as Sir Gawain, a knight at Camelot, the legendary castle where Arthur held court. “There is something in the Arthur legend for everyone,” says Leah Tether, a professor of medieval studies at Bristol University and former president of the British branch of the International Arthurian Society, which regularly brings together scholars and other enthusiasts interested in Arthurian literature. The story of King Arthur, she says, “has got flawed characters with whom we can empathize, quests to achieve impossible goals, and an adaptable story line that fits the sociopolitical landscape of the time.” Raluca Radulescu, a professor of medieval literature at Bangor University in Wales, suggests Arthur’s perennial appeal is also tied to “a standard of moral integrity” that readers find inspirational, one “they cannot find in the world around them, but will discover in the stories of King Arthur.”The timeless popularity of the Arthur legend has overshadowed a central, unresolved question: Was there really a King Arthur, or at least a historical prototype upon whom Geoffrey’s hero is based? That’s what has brought me to Tintagel on this stormy winter morning. Scutt leads me down a grassy slope to the foundations of a dozen houses built on terraces overlooking the sea. Ralegh Radford, the English archaeologist who exposed these ruins in the 1930s, was reminded of similar structures at remote sites in Ireland, and after observing Christian symbols on ceramics found at the site he guessed the ruins were the remains of a Celtic monastery that existed between the fifth and seventh centuries.

Over the past four years, however, Scutt and his team from English Heritage, a nonprofit organization that administers more than 400 historical sites in Britain, have conducted their own research, and they’ve challenged Radford’s assessment of the site. They have excavated three additional houses and have also unearthed fragments of glass goblets from Spain, cups from Merovingian-era France, pottery from Tunisia and amphorae from Turkey used for storing wine or olive oil. Carbon dating, unavailable to Radford a century before, has confirmed the settlement existed in the sixth century. But rather than being a retreat for religious ascetics, Scutt believes that the site, with its protected position on the Cornwall coast, was a flourishing local stronghold. “This could have been home to a mercantile elite whose economy was based entirely on trade,” he says.

Tintagel, Scutt says, was likely home to several thousand people and controlled a territory that extended across modern-day Cornwall. He points out that while much of the British Isles had sunk into illiteracy and destitution during this period—commonly known as the Dark Ages—most residents at Tintagel lived in comfortable slate-roofed homes with sturdy wooden timbers and, in some cases, a second story. It’s not implausible, he argues, that a ruler or commander—perhaps one named Arthur—rose out of this society, and served as an inspiration for Geoffrey of Monmouth. The headland has given up other tantalizing clues, including a sixth-century stone slab with the mysterious word “Artognou” carved into it. Experts in Celtic, the language spoken in Britain at the time, dismiss its significance. But some insist the inscription is a variation of “Arthur.” The slab, they say, is a mark of the king’s realm.

When the legend of Arthur was born, Britain was in a state of collapse. The Roman Empire had made its first incursion into the British Isles in 55 B.C., eventually conquering much of the territory up to present-day Scotland. Its conquest and long rule was often violent, but the Romans also built roads and established towns such as Londinium and Durovernum Cantiacorum, today London and Canterbury. Throughout the Roman province of Britannia the quality of life largely improved.

Then, in A.D. 410, Rome, under siege at home from Visigoths, a Germanic tribe from Eastern Europe, withdrew its troops and plunged Britannia into chaos. Civil institutions vanished, the economy collapsed, and basic household goods became scarce. Saxon invasions terrorized the population, and Britannia fragmented into fiefdoms dominated by often brutal strongmen and their gangs. “Britain has kings, but they are tyrants . . . engaged in plunder and rape, but always preying on the innocent,” a British monk named Gildas wrote in the sixth century. Plague and drought struck the region, wiping out a significant part of the population.

“Britain was a failed state,” says Marc Morris, a British historian and author of 2021’s The Anglo Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England: 400 to 1066. “It was a miserable time to be alive.”

Many historians believe that a heroic warrior likely rose during this period to lead the Britons, who had largely embraced Christianity, against the pagan Saxons. The Welsh poem Y Gododdin, written between A.D. 540 and 640, describes a fallen soldier by likening him to another called Arthur, which some scholars interpret as showing that a warrior named Arthur was so famous when the poem was written that the bravery of others could be measured by comparison. Around the same time, Gildas, the monk, described a British triumph at the Battle of Badon Hill, which he dated to “the year of my birth,” probably in the early sixth century. He didn’t mention Arthur (he called his hero Ambrosius Aurelianus), but three centuries later, around 830, a Welsh monk named Nennius, in his History of the Britons, described how a warrior named Arthur led the Britons to victory in 12 glorious battles against the Saxons. “The twelfth battle was on the mountain of Badon, in which there fell in one day 960 men from one charge of Arthur, and no one slew them except him alone, and in all battles he was the victor,” Nennius wrote.

Some scholars have pointed to Nennius’ account as evidence of Arthur’s existence. Yet Nicholas Higham, a retired medievalist at University of Manchester and the author of 2018’s King Arthur: The Making of the Legend, says the evidence is hardly conclusive. For one thing, the account was written 300 years after the Battle of Badon Hill was purported to take place. (Although Gildas’ text provides the only contemporaneous mention of the battle, other British histories, including the eighth-century Ecclesiastical History of the English People, describe the fighting in detail, and scholars are generally convinced that such a battle did take place.) For another, historians in the Middle Ages are widely known to have blended fact and fiction to advance a political or religious agenda. At a time when the Saxons were conquering Britain, Higham says, the Britons needed a “god-beloved warrior” to rally their spirits and restore the emergent nation to glory, and Nennius concocted a character to fit the bill. “Arthur was winning battles with the support of Jesus Christ and Mary against the Saxons,” he says. “The Saxons were presented as barbaric, dishonest and latecomers to Christianity.” To show that Arthur had roots in Roman culture, which was still widely admired, Higham argues, Nennius derived the name from Artorius, a general who gained fame in the Punic Wars in the third century B.C.

If Nennius established Arthur as a British hero, Geoffrey of Monmouth brought him to life. Born around 1090, possibly in Wales, and educated in Paris and Oxford, Geoffrey was ensconced as a bishop in Britain in the mid-1100s when he wrote, in Latin, perhaps the most influential book ever about Arthur. Like Nennius, Geoffrey had a political agenda: to show the superiority of the Celtic-speaking Britons, and by extension, the Welsh, who spoke the same language. “There were a lot of criticisms of the Welsh as being savages, barbarians,” says Morris. “Geoffrey invents a noble history for them, going back a hundred kings before Arthur.” A cipher in Nennius’ history, Arthur now became a Celtic-speaking warrior-king within a richly imagined narrative.

Geoffrey claimed that he’d gleaned details of Arthur’s life from an ancient Welsh history book shown to him by an Oxford archdeacon, but there’s no evidence such a book existed. There’s also no knowledge about what might have led him to set Arthur’s origin story at Tintagel, or if he ever visited the remote headland. “He would have known it as a very dramatic, rocky clifftop, a mystical place, a place that there were plenty of stories about,” says Higham. “But that’s all we can say.”

Geoffrey introduced Guinevere’s infidelity to Arthur, the wizard Merlin (a composite of earlier Welsh prophets) and a magical sword he called Caliburn (based on the Irish sword Caladbolg, a derivation of the Welsh Caledfwlch), which later became known as Excalibur. He ended the tale on an island called Avalon, where Arthur is carried by the enchantress Morgan le Fay after being “mortally injured” against the Saxons in the Battle of Camlann. Geoffrey apparently plucked this battle from The Welsh Annals, written in the late tenth century. This set of chronicles, an apparent blend of fact and fiction, established A.D. 537 as the year of “The Battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut”—or Mordred, who in later Arthurian tales becomes Arthur’s treacherous nephew and rival—“fell, and there was plague in Britain and Ireland.”

Geoffrey’s fantastical account had its share of skeptics. “It is quite clear that everything this man wrote about Arthur and his successors, and indeed his predecessors...was made up,” the medieval historian William of Newburgh wrote. Yet many Britons accepted it as the truth. In 1191 the monks of Glastonbury Abbey dug up a pair of skeletons in their churchyard and touted them as the remains of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere—a clever hoax to draw paying tourists to the abbey. By the 13th century, writes Morris in 2015’s A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain, “It was proof positive that the fabulous king about whom Geoffrey of Monmouth had written had once really existed.”

One true believer was King Edward I. In 1278, the monarch visited the grave site at Glastonbury and ordered the remains to be disinterred, partly to lay to rest the belief in some quarters that Geoffrey’s hero was superhuman and still alive—and thus could potentially challenge Edward for the throne. “There in two caskets were found the bones of the said king of wondrous size, and those of Guinevere, of marvellous beauty,” wrote a local observer. Afterward, the king and queen wrapped the skeletons in silk, placed the royal seal on them, and returned them to their graves.

From this point, the Arthur legend not only grew but became the dominant literary tale of medieval Europe. Monasteries and royal courts bought more than 1,000 copies of Geoffrey’s manuscript, making it the most popular text in the Middle Ages after the Bible. Richard Barber, an Arthurian scholar in Sussex, has personally tracked down 235 surviving copies. He might have found more, but when Henry VIII shuttered the country’s monasteries in the 1530s during his break with the Roman church, “A lot of them were torn up and used for wrapping pies,” Barber told me.

Meanwhile, Arthur’s legend traveled across the English Channel to France, thanks to the hugely influential 12th-century French poet Chrétien de Troyes. Possibly borrowing from Geoffrey and from Welsh folk tales, and writing under the patronage of the Plantagenets, the British-French dynasty founded by Henry II, de Troyes invented Sir Lancelot, Camelot and the Holy Grail, which he described as a “vessel” used by Jesus at the Last Supper. “The Arthur story began to take off,” says Barber. “One hundred years later, you’ve got Arthur in Germany and all around Italy.”

Manuscripts retelling the Arthur myth became so common that they were often discarded and recycled, and not only as pie-wrapping paper. One winter morning I visit the rare-book room at Bristol’s Central Library with Leah Tether, the University of Bristol medievalist. A library staff member brings us four leather-bound tomes written by the French philosopher Jean Gerson and printed in Strasbourg in the late 15th century. But what we’re really here to see is something that one of Tether’s colleagues discovered pasted inside the bindings in 2019: seven parchment manuscript pages written in Old French, dating to around 1250. These pages—discarded and recycled as protective filler inside the newer volumes—show how the Arthur legend took on embellishments and mutations as it proliferated across Europe, introducing new characters, developing story lines, and reflecting the mores and culture of the different societies in which it appeared.

The seven pages come from a series of French stories known as the Vulgate Cycle, and they constitute some of the oldest known adaptations of tales by Chrétien de Troyes. I scan the thousand-year-old parchment and spot references to “Merlin” and “Gauvain,” the French spelling of Sir Gawain. Here, Tether says, Merlin advises Arthur on military tactics, leads a charge using a dragon standard that breathes real fire, and engages in an amorous encounter with Viviane, otherwise known as the Lady of the Lake, a fairy queen invented by de Troyes and further developed by later French writers. This version, says Tether, is “more chaste” than standard French medieval accounts of the relationship, which describe a spell written across Viviane’s groin that prevents men from sleeping with her; in this early version the spell is written on her ring, and prevents men from “speaking” with her. “Very little is known about de Troyes’ life, but he’s the ultimate medieval storyteller,” Tether tells me. His stories were translated into Old Norse and Swedish—the latter, Tether says, inscribed on doors across Iceland in the 12th century.Other writers added their own touches to the Arthur story and canonized his place in literary history. Thomas Malory, a British member of Parliament and a violent criminal who probably wrote Le Morte d’Arthur while doing time in Newgate Prison for robbery or rape, created the definitive version of the Sword in the Stone story. In his account, the teenage Arthur answers a challenge inscribed on the stone—“Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvil, is rightwise king born of all England”—by performing the feat multiple times other nobles have failed. Four centuries later, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in Idylls of the King, described the tortured romantic triangle involving Arthur, Lancelot and Guinevere that tore apart the Knights of the Round Table: “The great and guilty love he bare the Queen, / In battle with the love he bare his lord, / Had marr’d his face, and mark’d it ere his time,” he wrote. Tennyson also brought the story full circle. The Victorian poet described the waves of the Bristol Channel carrying the infant Arthur, an abandoned castaway, to the shore of Tintagel. There Merlin stashes him in the grotto—now known as Merlin’s Cave—to protect him from the enemies of his father, Uther Pendragon.

As he had from the beginning, Arthur remained a source of legitimacy for Britain’s ruling elite. Where early medieval legends sought to cast Celtic-speaking Britons favorably, the Tudor monarchs, who came to power in the late 15th century, claimed Arthur as a direct ancestor, deriving from him the right to rule the nation. Henry VII even baptized his son Prince Arthur. And for writers, he remained the ideal vessel into which they could pour their social commentary. Tennyson, writing during the upheavals of the Industrial Revolution, portrayed Arthur as a figure of moral stability and certainty, whereas Guinevere, in the light of Victorian morality, was an adulterer whose transgressions contributed to the general sickness of society.

“The interesting thing about the Arthurian legend is that it has periods of both ebb and flow,” says Tether. “It’s able to be molded to fit with current preoccupations, such that it can find applicability no matter what the mood of the moment.” She points out that the elasticity of the narrative has its roots in the Middle Ages: “Stories were transmitted orally and via manuscripts, meaning that no two versions were identical. It’s actually impossible to identify an ‘original’ version of Arthur. Arthur’s appeal is, and always was, precisely in his multiplicity.”

In and around Tintagel, the legend of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Arthur continues to draw pilgrims to the king’s “realm.” The Earl of Cornwall’s 13th-century stronghold receives 250,000 tourists a year, including 3,000 a day in the summer. Many, says Win Scutt, “believe that they’re seeing King Arthur’s castle.” Critics say English Heritage has fed that misconception since taking over the site two decades ago. In 2016, two hundred Cornish historians criticized the group for turning the castle into a “fairytale theme park” by erecting kitschy monuments such as a Merlin relief carved into stone near the grotto. Scutt replies that his organization has made it clear that the castle is Richard’s, not Arthur’s. But, he adds, “there was a great mythology to this site that was denied up to this point.”

The theme park atmosphere carries over into the modern village of Tintagel on the Cornish mainland. Visitors can spend the night at the hulking Camelot Castle Hotel, hunt for souvenirs at the Pendragon Gift Shop, or grab a pint and a Cornish pasty—a traditional crescent-shaped pie filled with meat—at the King Arthur’s Arms Inn. Tour guides in North Cornwall, meanwhile, promote several sites, claiming the places may have once been frequented by King Arthur and his knights. There’s a pair of mysterious labyrinth symbols carved into a stone in a forest, supposedly during the Early Bronze Age (skeptics say it’s a fake done by a student in the 1930s); a Neolithic stone enclosure on the eerie Bodmin Moor that some say was an Arthurian ceremonial site; and St. Nectan’s Glen, a mossy waterfall where Arthur’s knights are said to have cleansed themselves before setting off to find the Holy Grail. Matt Ward, a manager at St. Nectan’s, and previously property manager of Tintagel Castle, says he’s convinced there’s something to the Arthur story. “I think Geoffrey of Monmouth heard about Tintagel from people at the time,” he tells me. “They told him, ‘There were powerful people up there—kings.’”

About five miles southeast of Tintagel lies the village of Slaughterbridge, which has laid its own claim to the Arthur legend. Joe Parsons and his family have owned an expanse of meadows and forest here for three generations; it was the site, he maintains, of the Battle of Camlann—King Arthur’s last stand. Geoffrey of Monmouth described the battle as a fatal showdown between King Arthur and his nephew, Mordred, who had raised a rebellion against him. “Arthur was filled with great mental anguish by the fact that Mordred had escaped him so often,” Geoffrey wrote. “Without losing a moment, he followed him to that same locality, reaching the River Camlann, where Mordred was awaiting his arrival.”

Parsons leads me down a dirt road from his small museum and gift shop through the forest to the rushing Camel River. Slipping down a wet slope, he straddles a mossy stone column that lies toppled over on its side along the riverbank. Known as the Slaughterbridge Stone, the column, apparently a burial marker, bears inscriptions in Latin and Ogham, an Irish script extant during the Dark Ages. The Cornish historian Richard Carew, in his 1602 Survey of Cornwall, was the first to document this slab, noting that “the olde folke thereabouts will shew you a stone, bearing Arthur’s name.” Some have claimed the last words of the worn-away inscription once read Latinus hic iacet filius Merlini Arturus, or “Here lies Latinus, the son of Arthur the Great.” Most, however, have read it as something more prosaic: Filius Magari, or “the son of Magari.”

Parsons imagines that in A.D. 537, a warrior-king named Arthur presided over a domain in Cornwall that was centered at the stronghold of Tintagel and guarded at its borders by half a dozen Iron Age hill forts that still stand. Then invaders—possibly Saxons, possibly a splinter group from Arthur’s British tribe—crossed the Bodmin Moor and made their way west across the marshy ground toward the Camel River. “This crossing of the river into north Cornwall was the last defense of that kingdom,” he tells me. At a fording point where the Camel joins the Alan River, he theorizes, the invaders met Arthur’s men in the epic clash. Both Arthur and Mordred, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, were mortally wounded.

Parsons rattles off evidence that he says supports this scenario: beside King Arthur’s stone, an A.D. 1086 reference to a nearby village called Tremordred, which Parsons suggests may refer to Arthur’s nephew; the fact that the Camel River joins the Alan River on his property, making the portmanteau Camlann (there are several other rivers throughout the British Isles with similar names); and a wealth of archaeological evidence that, he says, was found here in the 19th century. “Spurs, battle stuff, arrowheads, horse harness pieces, other bits of weaponry.” The trove of material was taken to a Cornwall museum, he says, “and then disappeared.”

But Nicholas Higham, who’s spent much of his career subjecting claims about Arthur’s historicity to scrupulous analysis, views the Camlann story as one more tall tale pieced together from specious “evidence.” He was an undergraduate at the University of Manchester in the early 1970s, he tells me, when “archaeology and history were surging” with attempts by respected academics to prove that King Arthur had really existed. In the 1960s, Leslie Alcock, an archaeologist at the University of Glasgow, conducted excavations at Cadbury Castle, a Bronze and Iron Age hill fort in England’s Somerset County that had long been identified by Arthurians as being the real Camelot. Alcock insisted he was “an agnostic” on the question of whether Arthur had really lived, but his discoveries of fine Mediterranean pottery fragments—similar to those found at Tintagel—as well as expansive fortifications stirred speculation, and he stoked excitement by writing a book in 1972 called Was This Camelot? The next year, an English historian named John Morris, who specialized in Roman-era and Dark Ages Britain, cited the sudden appearance of the name “Arthur” in sixth-century accounts as proof of the existence of the great warrior hero.

“There was extensive pushback,” Higham tells me. He joined the ranks of the skeptics himself. “What really got me fired up was the constant flow of very bad history writing. You’ve got a whole series of writers like Alcock and Morris who accept what is not recorded until the early ninth and tenth centuries as a factual account of what happened around A.D. 500. It’s nonsense.” Morris, the British medievalist, agrees. “It’s like asking about William Wallace based on Braveheart,” he says. “There’s no evidence for it.”

The investment of time and energy that scholars have put into the question of whether Arthur really lived—to say nothing of the enormous popularity of Arthurian tales through the ages—suggests that the pursuit goes far beyond narrow academic interest. Why are cryptic references in 1,500-year-old Celtic texts so tantalizing? Might it be they’re a way of transcending humdrum reality and connecting to a glorious past and the possibility that, deep in the mists of time, giants walked the earth?

Win Scutt, for his part, isn’t ready to write off King Arthur just yet. The four years that he spent working here impressed on him the “extraordinary nature” of this Dark Ages enclave, he says, as we perch on a slope overlooking the crashing sea on a windswept morning. At a time when most Britons were struggling to find cooking utensils, Tintagel’s inhabitants were using crucibles to forge metal, inscribing slabs with Celtic writing, and controlling agricultural production across substantial territory. The settlement would have been well defended against the marauding bands that plagued the mainland: Geoffrey of Monmouth noted that just a handful of warriors positioned at the narrow neck could have staved off an army. It is not difficult to envision a charismatic leader rising here to defend northern Cornwall from Saxon invaders, says Scutt, or to imagine that his feats would enter sixth-century folklore and be passed down by storytellers to Geoffrey and other chroniclers. “We know this was a center of power,” he says. “But whose power was it? It’s always going to remain a mystery.”

ARticle link

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/king-arthur-real-person-180980466/MY THOUGHTS

To me, growing up on High John and the Devil's Daughter I can say that the path of characters created in an environment that is not bound to books can not survive. Where Arthur went from a simple king victorious on a few battlefields, and modulated into the christian warrior with ideals that extend to places far from england.

High John is barely known by Black people in the USA. The why is simple. It isn't that High John isn't flexible. It is the identity of High John as a slave to whites that is not enslaved. The DEvil's daughter as the Devil's daughter, the daughter of a the embodiment of sin, undetachable from sin, who is a hero. That is the problem with both characters in a Black community post War between the States whose internal minorities want the larger black community to be christian or in positive association to whites. The two paths that the characters by default oppose.

But the question to what black fable started before the civil war in the black community in the USA can arrive stronger today is an interesting question. In england , Arthur had the luxury of a pre modern sense of storytelling or communal pride. In modernity, the idea of the global human family , has powerful priest or priestesses in the USA or elsewhere in humanity, which influences characters from any culture. -

A Festival That Conjures the Magic of H.P. Lovecraft and Beyond

At the Rhode Island event, revelers danced to murder ballads and celebrated all things weird. They even found time to reckon with the writer’s racism.

By Elisabeth Vincentelli https://www.evincentelli.comMatt Cosby of NY Times is the photographer

Aug. 28, 2022There’s bacon and eggs, and then there’s bacon and eggs at the Cthulhu Prayer Breakfast. Named after the cosmically malevolent and abundantly tentacled entity dreamed up by Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the event, among the most popular at NecronomiCon Providence 2022, filled a vast hotel ballroom at 8 a.m. on a recent Sunday.

To the delighted worshipers, Cody Goodfellow, here a Most Exalted Hierophant, delivered a sermon that started with growled mentions of “doom-engines, black and red,” “great hammers of the scouring” and so on.

Then the speech took a left turn.

“I must confess myself among those who always trusted that a coven of sexless black-robed liches would change the world for the better,” said Goodfellow, who had flown in from the netherworld known as San Diego, Calif. “But the malignant forces of misplaced morality have regrouped from the backlash that stopped them in the ’80s, and the re-lash is in full swing.”

And so it went, with delicious jabs at incel culture (of which, one might argue, Lovecraft was a proto-member) and plutocrats.

The conference, which took place on Aug. 18-21 in Providence, R.I., for the first time since 2019, is named after Lovecraft’s hometown and another of his literary inventions — a grimoire so dangerous that those who read it meet ghastly ends. (The biannual convention takes place around his birthday; he was born on Aug. 20, 1890.)

The problem is that Lovecraft was a deeply racist and xenophobic man. How we deal with the legacy of a decidedly unsavory person is an issue of great political and cultural relevance nowadays, and the event has tackled it not by retreating or trying to defend the indefensible but by opening up its programming and the range of people invited to participate.

Cordelia Abrams, 49, a Bostonian life coach dressed as an anglerfish at the breakfast, has been attending these events for almost a decade. “This is weird and literary and local,” she said.

Although the event was Lovecraft-centric in its 1990s iteration, it has broadened since a 2013 reboot under the aegis of the nonprofit Lovecraft Arts & Sciences Council and is now subtitled “the international festival of weird fiction, art and academia.” Which, of course, poses the question: What does weird even mean when swaths of the mainstream have a slipping grip on reality? A large number of folks, after all, falsely believe that satanic pedophiles operated out of a pizzeria.

At the “Welcome to the New Weird” panel, the editor and publisher Ann VanderMeer, one of the festival’s guests of honor, posited that “the weird is a way to connect with the world around us and make sense of it.” Most people I met or heard speak over the weekend agreed there was a common element of unease and unsettlement, which explains the panels dedicated to simpatico artists like Clive Barker, David Cronenberg and J.G. Ballard.

What was striking was how many of the participants have worked through the problem of Lovecraft himself to repurpose the basic tropes in his fiction. They are appropriating its overarching themes — the powerlessness of humanity against great, unknowable forces — and turning the weird into an instrument of self-exploration, liberation and creativity.

“What really brought me here is the fact that I love horror,” said Zin E. Rocklyn, a 38-year-old queer Black writer from Florida who was on three panels. “I love the catharsis that it brings, the truth that it brings. An incredible imagination came up with some really shady” garbage, she added, using a stronger word to describe Lovecraft’s views. “It’s based in ignorance and fear, but it taps into a universal fear. Being able to examine that and talk about that and expand on that is a great example of what you can do with such an ignorant business.”

Besides academic papers, the convention offered an abundance of panels sharing a dark sensibility: “Not Just Three Acts: Narrative Structure and the Weird”; “Out of the Shadows: A History of the Queer Weird”; and “The Horizon Is Still Way Beyond You: Zora Neale Hurston’s Life and Legacy.” For the last session, the panelists somehow wrangled an interesting 75 minutes out of Hurston’s and Lovecraft’s irreconcilable differences — contrasting, for example, her searching curiosity about other people with his bigotry.

Among the most eye- and mind-opening panels was the one on body horror, which, for you literary fiction folks, included a reminder that the subgenre encompasses classics like “Frankenstein” and “The Metamorphosis.” That panel felt pointed at a time when control over one’s body is being hotly debated in issues relating to transgender lives and abortion.

Another bracing session dealt with Lovecraft and Southeast Asia, in which the Indonesian-American writer Nadia Bulkin said she loved the idea that Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones (ancient gods as powerful as they are malignant) “are the European invaders trampling on lands that aren’t theirs.” Cassandra Khaw, a Malaysian-born writer and another guest of honor, pointed out an essential distinction between Asian horror movies and their American remakes: The American versions are inferior because they add an element of salvation or moral redemption where there was none.

But many attendees preferred gaming over metaphysical discussions. Several sessions were spread over various tables, mostly on two floors, and ranged from the popular (“Call of Cthulhu,” which is widely credited to have reignited interest in Lovecraft when it came out in 1981) to the willfully obscure (“Hecatomb,” a failed collectible-card game meant to be a dark version of “Magic: The Gathering”) and the hilariously entertaining (“Pirate Borg,” complete with swashbuckling outfits and a screen showing close-ups of the dice rolls).

The volume and variety of the programming was enough to make your head spin like Regan MacNeil’s. There were also film screenings, readings, concerts, live podcasts, walking tours of Lovecraft’s Providence, an art exhibit and theatrical performances. There was even a mushroom jaunt in a nearby park, in tribute to the recurrence of things fungal in Lovecraft’s fiction.

According to Niels Hobbs, the “arch director” of the convention and a marine biologist at the University of Rhode Island (he was on the “Under the Sea: Horrors of the Deep Ocean” panel), this year’s edition drew around 200 guest panelists, artists and reading authors; over 100 volunteer staff members and “minions”; and 1,400 attendees. (Absent from the official proceedings was the pre-eminent Lovecraft expert S.T. Joshi, who later wrote in an email that he had been at NecronomiCon but “kept a low profile.”)

Some preferred focusing on the core mythos, like Brian Vann, 53, a data analyst from Costa Mesa, Calif. “His characters are so frequently warned off: ‘Don’t go there, bad things happen,’” Vann said. “But they go, with terrible results. That speaks a lot to the human condition: How do we just ignore the warnings?”

In comparison to commercial enterprises like Comic Con, Providence had no Hollywood presence and only an infinitesimal amount of cosplay. The one big event that involved dressing up, the Eldritch Ball, had a theme, “Masque of the Red Death,” that freed up the imagination rather than constricted it to trademarked characters — instead of, say, Darth Vader, there was a woman dressed as Persephone, queen of the underworld, and a tuxedoed man in what looked like a green crochet Cthulhu mask. Revelers slow dancing to murder ballads was a sight to behold.

Lovecraft himself might have been surprised to see his work bringing together such an inquisitive, welcoming congregation. But to Goodfellow, 53, the conference is a good antidote to the nihilism ravaging parts of America.

“Instead of rooting for the apocalypse, we’re rooting for sustainability and for people to radically accept each other as who we are and all move forward together,” he said. “It’s a wonderfully ironic backhanded way of finding positivity in absolute negativity.”

Article link

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/28/books/necronomicon-providence-hp-lovecraft.html

My Thoughts

I am not a fan of the squid god:) But I never knew of the festival and it seems on reading like what the comic con used to be in NYC, what jazzmobile used to be in harlem, what many festivals used to be that I liked once upon a time.

I oppose the idea that Lovecraft was unsavory. Hitler as leader in the german government did many things that hurt people, whether german or not, ala The romani. But, Hitler had friends. I have never supported Donald Trump's as a real estate man or reality television mogul or president of the united states of america. But I don't know Donald Trump. The white men of european descent who enslaved my forebears , before during or after slavery , I do not like or support or have positive thoughts to. But that doesn't mean they were unsavory. Said white men had friends and loving ones. JK rowlings isn't unsavory. She has positions or viewpoints many do not like, many oppose, many despise, but that doesn't mean she is unsavory. An artist person not fitting a heritage or cultural mold in any community isn't a problem. Their art can still be liked. The problem is communities who confuse liking an art to liking an artist. I don't like the Nazi German party as I am black and by their law I am unfit to live or be treated with positivity if they have control to determine things. But, their night marches are lovely.

The article shows in this convention, the people who attend it were able to do what I have heard or read many artist say they can not do, to Michael JAckson or R Kelly or Bill Cosby or Harvey Weinstein or DW Griffith and that is separate the artists from the art. And that shows a maturity that is rarer or rarer within the consumers or creators of art. -

The Last Homily On Liturgoid

Audio

https://www.kobo.com/us/en/audiobook/the-last-homily-on-liturgoid

Colored Mural

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Mural-of-Beginnings-and-Mural-of-Ends-Colored-927830149

Coloring page Mural

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Mural-of-Beginnings-and-Mural-of-Ends-Coloring-pag-927830557

Text

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/The-Last-Homily-On-Liturgoid-927819243

For Dreadful Tales issue 40

https://www.deviantart.com/leothefox/art/Dread-Deadline-Forty-01-921208219Enjoy the excerpt below

-

Introducing the GanYok, the monster partner for Princess Candace as she is on her Legendary Bloody Melee Gatlopp Run on the planet called Dahesh

Colored page

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Invitation-A-Moment-In-the-LEgendary-Bloody-Melee-927346127

Black and white page

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Coloring-page-A-Moment-In-the-LEgendary-Bloody-Me-927346301

Storyboardfilm

https://richardmurrayhumblr.tumblr.com/post/693729651227492352/princess-candace-has-a-monster-partner-it-is-of....

PRincess Candace Videos

https://www.deviantart.com/hddeviant/art/Videos-of-Princess-Candace-927354237

-

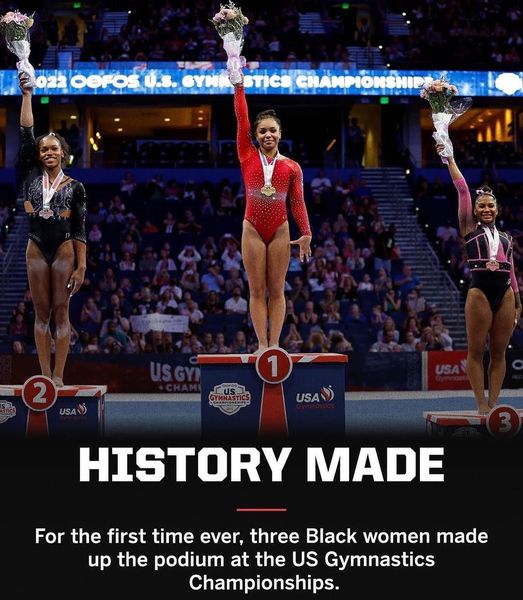

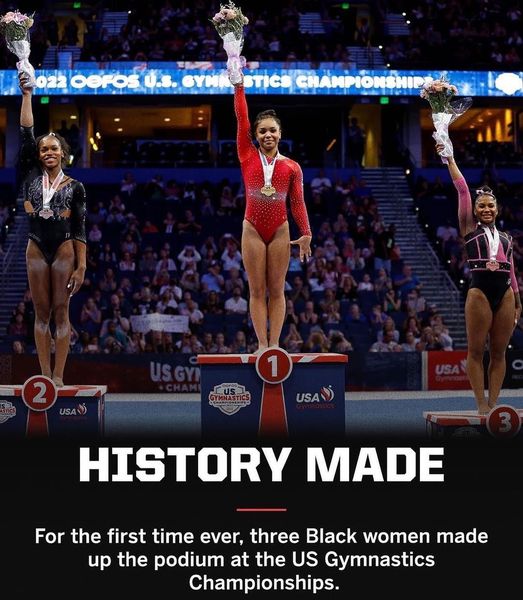

Congrats to these three Black female athletes, but for the record, lacking opportunity isn't about you. Individuals do have limits. So for those black female athletes in places where they are still restricted/blockaded/not opportune... you are just as great as these three black athletes who stand on podiums aside each other.

The goal isn't to make history. The goal is to be free. And if you are still not free to be in the USA , leave for other places. Don't wait for the USA to change. Find a new place, where you can be.FROM

A’Dorian Murray-Thomas Newark Public Schools Board Member

https://www.adorian.org/It’s never too late to make history!

We Love To See It!

In a historic first, Black women stood proudly in the All-Around podium at the U.S. Gymnastics Championships!

Konnor McClain @konnormcclain_

Konnor McClain @konnormcclain_

Shilese Jones

Shilese Jones

@shicanfly

Jordan Chiles

Jordan Chiles

@jordanchiles

THIS is the legacy of

#GabbyDouglas #SimoneBiles #DominiqueDawes and so many other trailblazers who trained and stood alone.

#KonnorMcClain

#ShileseJones

#JordanChiles

#BlackGirlMagic

#Gymnastics #SHEWins #HERstory #TuesdayVibes #USA

#BlackHistoryIsAmericanHistory

-

MONICA RAMBEAU: PHOTON #1 (OF 5)

Written by EVE L. EWING

Art by MICHAEL STA. MARIA

Cover by LUCAS WERNECK

On Sale 12/7THOUGHTS ON THE ARTICLE BELOW

Where to begin...first, even though some know it, all do not. The whole captain marvel comic book line was created to keep a name safe. DC Comics denied the original creator of the first character named captain marvel to exists. Then DC bought that company. But, Before DC bought that company, MArvel comics realized, DC comics having a character named Captain Marvel would be just ... so to keep a trademark, they have to publish a captain marvel comic for the legal sake.

So, this is a comic book born from fiscal warfare... That is the first problem. Art has nothing to do with the genesis of the Captain Marvel line in Marvel Comics.

Second, because this comic book line was never about artistic quality, but always legal activity, it probably has <I didn't check> the longest comic book run without any consistency in the marvel comics universe. Marvel has to keep the making captain marvel comics for the name. But, the nature of the USA comic book industry is to make erratic plot changes to characters over time.

Third, the greatest erratic plot twist to captain marvel was when Marvel Comics now owned by Disney, decided to make Ms Marvel, Captain Marvel and give the mantle of Ms Marvel to a young female non white/non christian acolyte/arab. Which on its own, you may suggest, what is the problem? In the line of Captain Marvel's was already someone not male/not white/not european who had already been rechristened, not killed like the first marvel captain marvel <poor patriarchy> three times. So the original female Captain Marvel was technically still alive in the Marvel Comics universe as spectrum or pulsar or photon but Marvel decided to make Ms Marvel , captain marvel.

It is called plot quagmire.

As a writer, it disgusts me. The comic book industry in the USA's great flaw is the disrespect to plot. Plot means nothing. Reboot universes, kill off, always do random radical things. I argue, what will the USA comic book world be if all the comic books, Marvel + DC+ all the smaller prints, actually kept to a real plot, and never cheated or schemed or did silly radical things, but actually kept to plots.Now, as someone who supports Black artists, and knows the importance of Black characters in majority white owned/employed media organizations in the USA to a large ,not necessarly majority, percentage of black people in the USA. I say, the new photon comic book is great on arrival.

Black Woman, slick outfit- no cape nonsense, glowing fists- punch everybody, flying through space with no need for a suit while her makeup is perfectly on and she has a creamy crack hairdo, so near godlike. Drop the Mic buy the comic, and start reading, and get to cosplaying.Storywise, I have long since, left the USA comic book world. I enjoy images and I don't bother with most stories. Cause I don't appreciate the reboot nature. That is silly to me. But, love the look.

SOME OTHER THOUGHTS OF MINE ON SUPERHERO-DOME

Is Superman Outdated?

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1905&type=status

Multiracial in multiversal

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1967&type=status

Making more money by changing the palette

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1562&type=status

reparations in comic book world

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1712&type=status

Does Disney need to buy Milestone?

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1663&type=status

I don't publish agenda that isn't from my heart

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=1514&type=statusTHE ARTICLE

Photon's Limitless Power Threatens to Break the Marvel Universe in Monica Rambeau's First Solo Comic Series

Eve L. Ewing and Michael Sta. Maria launch 'Monica Rambeau: Photon,' a new limited series coming in December.

BY MARVELThis December, universal powerhouse Monica Rambeau will star in first-ever solo comic series! A five-issue limited series, MONICA RAMBEAU: PHOTON, will be written by award-winning author and scholar Eve L. Ewing and drawn by new Marvel talent, artist Michael Sta. Maria. The iconic Marvel super hero with four decades' worth of amazing stories will at long last headline her own saga.

From the New Orleans Harbor Patrol to the Avengers to the Ultimates, Monica Rambeau has been a leader and team player her entire life, but now she’ll face a reality-shattering crisis that she’ll have no choice but to take on single-handedly. In order to do so, Photon will need to reach new heights of her incredible abilities—and then surpass them!

In a revelatory journey spanning time and space, fan will behold Photon’s true potential. The adventure begins when Photon is charged with making a very special, very cosmic delivery. What should be light work (get it?) for Monica becomes increasingly complex and dangerous due to a threat from beyond and family drama.

“It's such an honor to be taking on the story of a legacy character like Monica Rambeau,” Ewing said. “Monica's character has a long history in the Marvel Universe, but she's way overdue for getting her own story told. I'm picking the pen up from the legend himself, Dwayne McDuffie, who put out the last Monica Rambeau solo adventure almost three decades ago. It's a privilege and I'm excited to tell the story in a way that both highlights her incredible cosmic abilities as well as her everyday, relatable struggles. I hope this will be a title that has something equal to offer to veteran readers and folks who may be brand new to comics.”

Explore the outer reaches and wildest vagaries of the Marvel Universe through the eyes of one of its most powerful heroes when MONICA RAMBEAU: PHOTON #1 arrives in December.

ARTICLE LINK

https://www.marvel.com/articles/comics/photon-monica-rambeau-first-solo-comic-series-eve-l-ewing

-

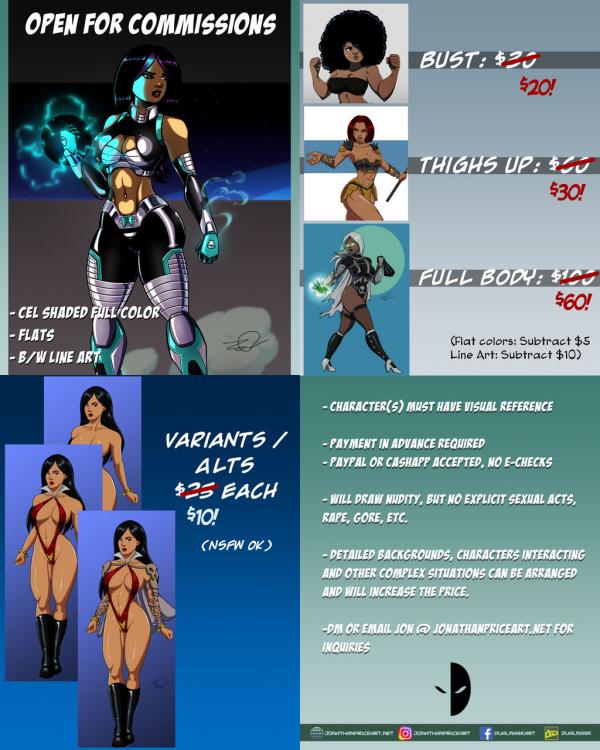

UPDATE: Prices reduced for the summer! Get 'em while they're hot! Open for ten slots right now!

Decided to put together a modified price sheet for the kinds of commissions I'm currently accepting. This is the current pricing for the foreseeable future.

If you are interested, contact me at jon@jonathanpriceart.net or send a note!Commissions Open! - SUMMER SALE by Dualmask on DeviantArt

-

Why there's a 'high bar' for new EV tax credits, according to a Biden economic adviser

Akiko Fujita

Akiko Fujita·Anchor/Reporter

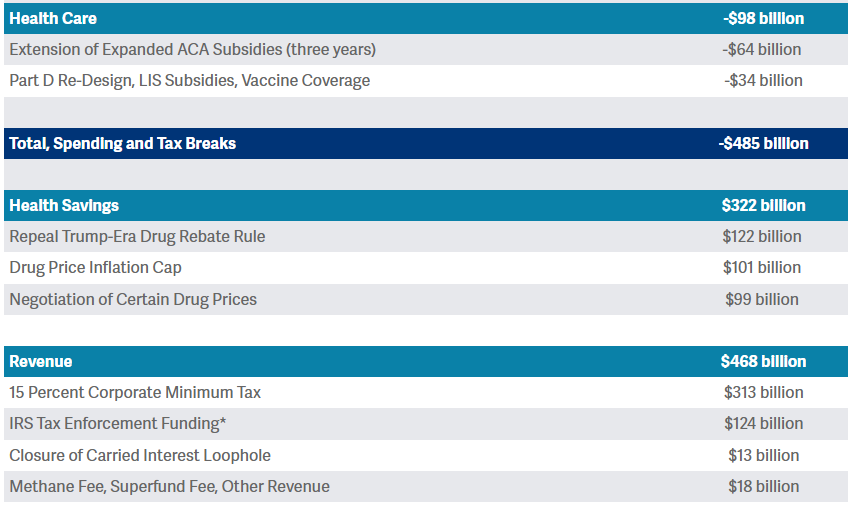

Thu, August 18, 2022 at 9:16 AMThe White House’s top economic adviser defended restrictions placed on the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)’s key tax credits that are intended to accelerate electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

Under the new bill President Joe Biden signed into law on Monday, drivers are eligible for a $7,500 tax credit for new EVs or $4,000 for used vehicles largely sourced and manufactured in the U.S.

However, critics — including some carmakers — have criticized the administration for limitations placed, saying it’s likely to slow down the adoption of EVs and leave drivers with few options.

“Certainly, it sets a high bar that that tax credit is eligible for batteries and vehicles that are produced in the United States or in North America or countries that we have free trade agreements with,” Brian Deese, director of the National Economic Council, told Yahoo Finance Live (video above). “We think that that's an appropriate bar because what we want across time is to provide a strong incentive for us to have secure supply chains in those areas.”

Specifically, the new law restricts the full tax credit to EVs with battery material sourced from the U.S. or free-trade partners, starting in 2024. Any minerals or components sourced from “foreign entities of concern” including China would not qualify for the $7,500 credit. Final assembly of the vehicle would also need to take place in North America.

Adding to the restrictions, the law only applies to vehicles with a manufacturer suggested retail price (MSRP) below $55,000 for cars and below $80,000 for trucks and SUVs.

A necessary step

Biden has hailed the hundreds of billions of dollars committed to tackling climate change through the IRA as “one of the most significant laws in recent history,” but carmakers have criticized the new legislation for attaching too many strings and limiting the wide-scale adoption of clean cars.In a recent interview with Yahoo Finance Live, Fisker CEO Henrik Fisker called the restrictions counterproductive, arguing that the limitations would actually “slow the adoption of EVs.”

“It's going to offer less choice to the consumers," he said. "I'll be surprised if there's even 10 vehicles in the US that will qualify for the full amount."

An analysis by the Congressional Budget Office estimated the $85 million set aside for new EV credits in the 2023 fiscal years would only translate to 11,000 new vehicles sold under the $7,500 credit. That pales in comparison to roughly 630,000 EVs sold in 2021 just in the U.S.

Deese said the “high bar” is a necessary step to entice carmakers into investing in supply chains closer to home. An overwhelming majority of minerals and components used in vehicles today are currently sourced from China.

Specifically, the new law restricts the full tax credit to EVs with battery material sourced from the U.S. or free-trade partners, starting in 2024. Any minerals or components sourced from “foreign entities of concern” including China would not qualify for the $7,500 credit. Final assembly of the vehicle would also need to take place in North America.

Adding to the restrictions, the law only applies to vehicles with a manufacturer suggested retail price (MSRP) below $55,000 for cars and below $80,000 for trucks and SUVs.

A necessary step

Biden has hailed the hundreds of billions of dollars committed to tackling climate change through the IRA as “one of the most significant laws in recent history,” but carmakers have criticized the new legislation for attaching too many strings and limiting the wide-scale adoption of clean cars.In a recent interview with Yahoo Finance Live, Fisker CEO Henrik Fisker called the restrictions counterproductive, arguing that the limitations would actually “slow the adoption of EVs.”

“It's going to offer less choice to the consumers," he said. "I'll be surprised if there's even 10 vehicles in the US that will qualify for the full amount."

An analysis by the Congressional Budget Office estimated the $85 million set aside for new EV credits in the 2023 fiscal years would only translate to 11,000 new vehicles sold under the $7,500 credit. That pales in comparison to roughly 630,000 EVs sold in 2021 just in the U.S.

Deese said the “high bar” is a necessary step to entice carmakers into investing in supply chains closer to home. An overwhelming majority of minerals and components used in vehicles today are currently sourced from China.

“The core of this bill on the clean energy side is to provide long-term technology-neutral tax credits so that we generate lower carbon energy here in the United States and we generate the technology and the technological advances that come with that,” he said. “We certainly expect that because of this legislation, companies and the suppliers in the supply chain are going to respond quite significantly.”

Companies like General Motors (GM) have already responded by seeking out minerals sourced in the U.S, and investing in mining operations in places like California. But the timeline for completion of those projects still remain years away.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation — a trade group that counts Toyota (TM), Ford (F), and GM among its members — estimated that 70% of the 72 EV models currently sold on the market will be ineligible for the new car tax credits because of the restrictions.

In the immediate term, Deese said, the $4,000 tax credit for used cars would likely accelerate adoption, given that the same limitations do not apply.

“Most Americans who are out there buying vehicles are actually buying used cars, particularly lower working class folks,” he said. “So we have more electric vehicles in our vehicle mix. Having a credit for used vehicles is incredibly powerful. It helps broaden the number of Americans who could see themselves getting into an electric vehicle."

Akiko Fujita is an anchor and reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @AkikoFujita

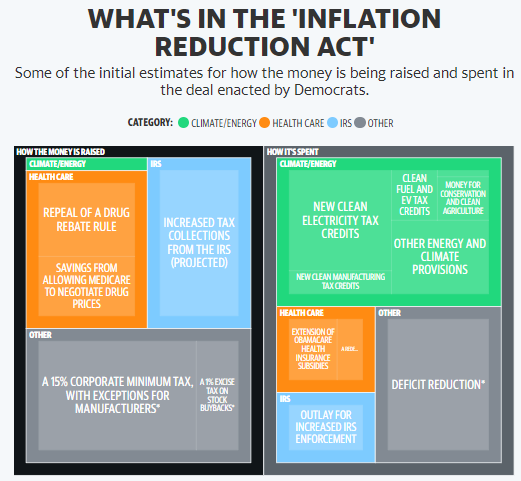

What's In the Inflation Reduction Act?

JUL 28, 2022

Update (8/11/2022): The Senate passed an amended version of the Inflation Reduction Act on August 7, which included several changes to the bill's tax and prescription drug provisions. While the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has indicated a full score of the amended bill will be published in the coming weeks, the Joint Committee on Taxation has released an updated score of revenue provisions in the bill, showing the new version would raise an additional $22 billion in revenue. However, we anticipate the prescription drug savings provisions will now save less than the $322 billion in the previous version. We will update this analysis once CBO releases its full score of the bill.

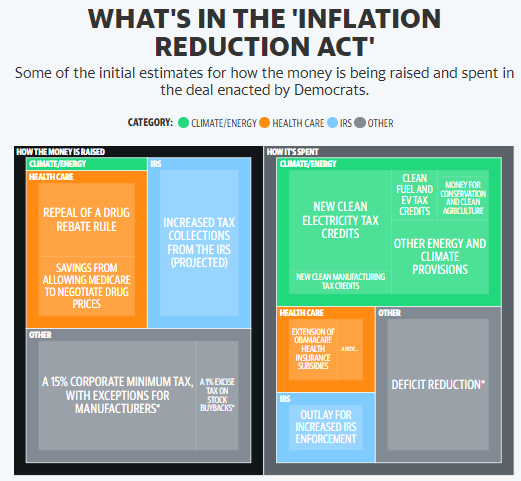

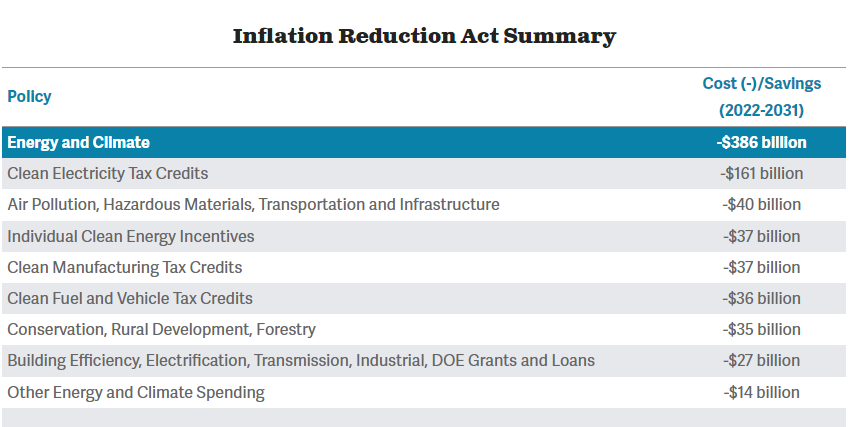

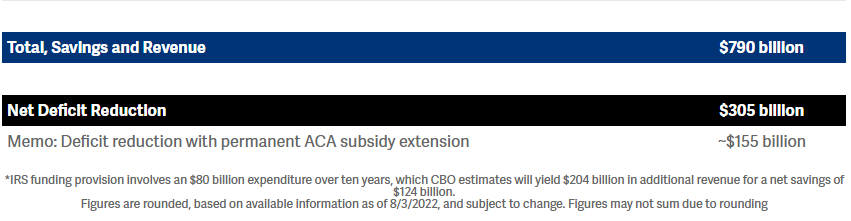

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just released its score of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, legislation which would use Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 reconciliation instructions to raise revenue; lower prescription drug costs; fund new energy, climate, and health care provisions; and reduce budget deficits.

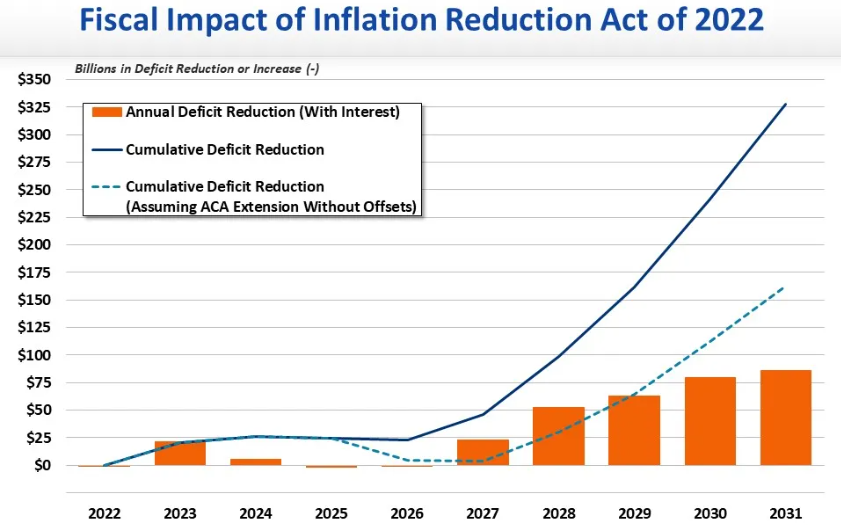

Based on the CBO score, the legislation would reduce deficits by $305 billion through 2031 – including over $100 billion of net scoreable savings and another $200 billion of gross revenue from stronger tax compliance.

Because the prescription drug savings would be larger than new spending, CBO finds the legislation would modestly reduce net spending by almost $15 billion through 2031, including by nearly $40 billion in 2031.

Once fully phased in, the plan would also slightly cut net taxes by about $2 billion per year – with expanded energy and climate tax credits roughly matching the size of new tax increases. The legislation would generate nearly $300 billion of net revenue over a decade, mostly from improved tax compliance and the spillover effects of higher wages as a result of lower health premiums -- neither of which are tax increases -- along with early revenue collection as corporations shift the timing of certain payments.

Overall, CBO estimates the legislation includes $790 billion of offsets to fund roughly $485 billion of new spending and tax breaks (as negotiators account for the policies, it includes $739 billion of offsets and $433 billion of investments). Unlike prior versions of this reconciliation bill, such as the House-passed Build Back Better Act, this legislation would reduce deficits. Along with other elements of the bill, it is likely to reduce inflationary pressures and thus reduce the risk of a possible recession.

The package includes $386 billion of climate and energy spending and tax breaks – mainly for new or expanded tax credits to promote clean energy generation, electrification, green technology retrofits for homes and buildings, greater use of clean fuels, environmental conservation, and wider adoption of electric vehicles, among other purposes. The package would also increase health care spending by nearly $100 billion, mainly by extending the American Rescue Plan's temporarily-expanded Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium tax credits for an additional three years, through 2025. Accompanying this new spending would be various regulatory and permitting reforms to help reduce energy costs outside of the reconciliation package.

The $485 billion of new costs would be offset with $790 billion of additional revenue and savings over a decade. This includes roughly $313 billion from imposing a 15 percent minimum tax on corporate book income; $322 billion for various reforms to reduce prescription drug costs; $124 billion ($204 billion gross) from reducing the tax gap through stronger Internal Revenue Service (IRS) enforcement; $13 billion from closing the carried interest loophole; and $18 billion from fees on methane emissions, Superfund cleanup sites, and a permanent extension of the higher tax rate for the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund.

The legislation would reduce deficits by over $20 billion in the first year, and – with interest – over $85 billion in 2031. We recently estimated it would reduce debt by nearly $2 trillion over two decades. Assuming the permanent unpaid-for extension of ACA subsidies (which we would strongly oppose), the plan would likely save almost $50 billion per year by 2031.

Although reconciliation was designed for deficit reduction, this would be the first time in many years it was actually used for this purpose. It would also be the largest deficit reduction bill since the Budget Control Act of 2011. With inflation at a 40-year high and debt approaching record levels, this would be a welcomed improvement from the status quo.WEBPAGE

https://www.crfb.org/blogs/whats-inflation-reduction-act