-

Posts

4,189 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

121

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

Cool resource alert: Variety has reported that Solange, through her Saint Heron studio, is launching a community library of “esteemed and valuable” books by Black creators. Readers can borrow any book from the collection of rare, author-inscribed and out-of-print literary works to up to 45 days, free of charge in the U.S. According to Saint Heron’s materials, the library’s focus is “education, knowledge production, creative inspiration and skill development through works by artists, designers, historians, and activists from around the world . . . We believe our community is deserving of access to the stylistically expansive range of Black and Brown voices in poetry, visual art, critical thought and design.”Rosa Duffy, founder of For Keeps Books, an Atlanta-based community bookstore and reading room, has guest curated the first season of the Saint Heron Library; in collaboration with Saint Heron, Duffy has curated over 50 available titles including a signed first edition of In Our Terribleness by Leroi Jones, Meren Hassinger 1972-1991, a signed The Meeting Point by Austin Clarke, My One Good Nerve Rhythms, Rhymes, Reasons by Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, inscribed by the authors to Maya Angelou, and more. The first season, supported by Aesop Skincare, will run from October 18th until the end of November.

“The Saint Heron Library continues the work we have been building by preserving collections of creators with the urgency they deserve,” said Solange in a statement. “Together we seek to create an archive of stories and works we deem valuable. These works expand imaginations, and it is vital to us to make them accessible to students, and our communities for research and engagement, so that the works are integrated into our collective story and belong and grow with us. I look forward to the Saint Heron library continuously growing and evolving and over the next decade becoming a sacred space for literature and expressions for years to come.”

You can read an interview with Rosa Duffy, guest curator of Saint Heron Library’s first season, on Saint Heron’s website.

SAINT HERON website: https://saintheron.com/

ARTICLE By Walker Caplan

https://lithub.com/solange-has-launched-a-community-library-of-rare-books-and-art-by-black-creators/When her phone buzzed on June 6, Iole Lucchese was still absorbing a shock that had come the day before. Her longtime boss, M. Richard Robinson Jr., the chairman and chief executive of the Scholastic publishing company, had died suddenly while taking a walk with one of his sons and his former wife on Martha’s Vineyard.

Now, Scholastic’s general counsel, Andrew Hedden, was on the phone, delivering a second surprise.

He had called to inform her that Mr. Robinson, 84 — who turned his father’s book and magazine business into the largest publisher and distributor of children’s books in the world, known for thousands of beloved series, including Clifford the Big Red Dog, Hunger Games and Harry Potter — had left Ms. Lucchese 53.8 percent of Scholastic’s Class A stock. The company where she had worked for 30 years, rising from a junior employee in the Canadian market to one of its top executives, was now a company she controlled.

“It was overwhelming,” Ms. Lucchese said in an interview at Scholastic’s headquarters in SoHo, water towers punctuating the cityscape behind her.

Being handed control of the company, which is valued at $1.2 billion, has made Ms. Lucchese, 55, one of the most powerful women in book publishing, and the stock provides her — the daughter of a construction worker and a homemaker — with significant wealth. The gift also shifts the business, which had been passed from father to son, to a person outside the family and puts Scholastic in an extremely unusual position for a public company: adapting to a succession plan many key players did not know was coming.

In his will, Mr. Robinson described Ms. Lucchese (her name is pronounced YO-lay lew-KAY-zee) as “my partner and closest friend.” But an article in The Wall Street Journal described them as “longtime romantic partners.” Six former employees, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were reluctant to cause further embarrassment to Mr. Robinson’s sons, confirmed to The New York Times that the romantic relationship between Ms. Lucchese and Mr. Robinson had been well known among many Scholastic employees.

“We were great business partners and close friends,” said Ms. Lucchese, a senior executive responsible for strategy and the company’s entertainment division.

She declined to address The Journal’s claim that she and Mr. Robinson had been involved in a relationship, which the employees believe ended a few years before his death.

This was Ms. Lucchese’s first interview with the news media since the death of Mr. Robinson, whom everyone called Dick. She was joined at a round conference table by Peter Warwick, the company’s new chief executive, and flanked by two publicists, one from Scholastic and another from the public relations firm Edelman.

“Dick understood that I shared his passion for Scholastic, and what this company means to the teachers we serve, to the children we serve, to everyone,” Ms. Lucchese said of his decision to leave his Class A shares to her. “He trusted me with that legacy, and I think it’s because we worked together and he knew that we were aligned.”

That bequest bypassed his two sons, John Benham Robinson, 34, known as Ben, and Maurice Robinson, 25, known as Reece. Mr. Robinson’s sons declined to comment for this article.

Scholastic said in a statement that the board had regular discussions about succession at the company.

The publisher's offices are in a warehouse-style building with exposed bricks, subway tiles and a giant sculpture of Captain Underpants busting through the lobby wall. On the day of the interview, the offices sat mostly empty as many employees continued to work from home because of the pandemic. Any silences in the conversation hung heavily in the air.

Sometimes confining herself to one-word answers, Ms. Lucchese discussed her career and the unusual situation of being both a longtime senior executive and now also the chairwoman. A stack of Harry Potter books kept watch from a large wooden bookshelf over Ms. Lucchese’s left shoulder.

“He’s the boss,” she said, motioning to Mr. Warwick, who, as chief executive, in one sense outranks her.

“But I do report to the board,” he answered.

Scholastic did not seek publicity for its new chair, the first woman and the first person outside the Robinson family to hold the position in decades. A few days after the news of the personal complexity around the succession had broken in The Journal, the company, known for its stable of beloved childhood classics, became an object of tabloid interest — “How ‘chameleon’ Iole Lucchese won $1.2B Scholastic empire,” read one New York Post headline.

When a reporter for The New York Times emailed Scholastic in August requesting an interview with Ms. Lucchese, Ira Gorsky, executive vice president at Edelman, the public relations company, called to inquire about whether Ms. Lucchese would be asked about “the alleged affair,” saying, “You can see how this is offensive, how the allegations implied that she has not gotten to her position because of merit.”

Mr. Gorsky said that as “a ground rule for giving an interview,” the Times reporter could not ask Ms. Lucchese about a personal relationship with Mr. Robinson. When the reporter declined to agree to such limitations, Mr. Gorsky responded: “Then we’re done.”

Ms. Lucchese did eventually agree to be interviewed, and no one representing her asked again for restrictions on topics or questions. Aside from an hourlong conversation with Ms. Lucchese and Mr. Warwick, preceded by a tour of the company’s archive led by a librarian, Scholastic declined to make any other employee available.

Her supporters say that as a 30-year veteran and a longtime senior executive of the company, she represents continuity and is qualified to lead it. Any skeptical reaction to Mr. Robinson’s choice of Ms. Lucchese is “laced with sexism,” said Erik Feig, the founder of Picturestart, a media financing and production company that Scholastic invested in and where Ms. Lucchese is a board member.

“She understands every brick of the literal and metaphorical building of the company,” Mr. Feig said.

Wall Street does not know her as well as some players in Hollywood do. Scholastic’s largest investor, after the Robinson family, was not aware of Mr. Robinson’s succession plan. “On a number of occasions, I asked Dick,” said David Wallack, a portfolio manager for T. Rowe Price, the Baltimore-based investment company, which holds more than 18 percent of the company’s common stock.

“He would tell me, ‘When I die, there is a safe, and there is an envelope in the safe, and the board of directors will open the safe and see what my wishes were,’” said Mr. Wallack, who was in regular touch with Mr. Robinson for 20 years. “I thought it was hyperbole.”

In its statement, Scholastic described the transition process this summer as smooth and efficient, saying that an interim team had taken over, as planned, immediately after Mr. Robinson’s death and that six weeks later, Mr. Warwick and Ms. Lucchese had been appointed to their new roles.

“Throughout this period — which was also set in the challenging landscape of schools reopening after Covid-shut downs — the company ensured the seamless continuation of operations, supporting teachers and students during a historic back-to-school season,” the statement said.

Mr. Wallack said he had hoped that after Mr. Robinson died, the board would conduct a broad search of internal and outside candidates for the chief executive role and elevate a board member to chair. He said that in July, when the board named Mr. Warwick, a board member since 2014, as chief executive and brought Ms. Lucchese onto the board as chairwoman, “we were shocked for sure.”

He said Mr. Robinson had never spoken to him of Ms. Lucchese and had never shared any information with him about her contributions to the company.

Mr. Wallack said that he couldn’t assess her skills himself. “I have never met her,” he said, “and none of my colleagues have met her.

After she was named chairwoman, Mr. Wallack waited to hear from Ms. Lucchese. “We are the largest shareholder after the family, and you would expect the company chairman to reach out and have a conversation with the shareholders she is supposed to represent.”

Mr. Wallack contacted an investor relations representative in June and again in September to request a meeting with Ms. Lucchese. “We were told they would let us know when she is available,” he said, adding that he was still waiting.

Mr. Hedden, the company’s general counsel, a board member until this summer, and the coexecutor of Mr. Robinson’s estate, said in a statement that he was not aware of Mr. Robinson’s plans. “From my knowledge of Dick, I know that he made his decisions around his will privately, as was his nature,” Mr. Hedden said, “and that he had the best interests of Scholastic and the continuation of his legacy in mind.”

But Mr. Robinson’s legacy includes a messy succession drama that spills into family drama as well. His will names Ms. Lucchese a coexecutor and gives her his personal property, “with the request, but not the direction” that she distribute it to his children in what “she believes to be in accordance with my wishes.”

The fact that the leadership of a public company hinged on the surprising bequest could represent a breach of duty on the part of the board, said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, senior associate dean of leadership studies at the Yale School of Management.

“If he were 40 years old, they should have had a plan,” Professor Sonnenfeld said. “And when you’re talking about an octogenarian, the odds are not in his favor.”

Ms. Lucchese was raised in Toronto, the younger of two sisters, and went to the University of Toronto. In 1991, she recognized the Scholastic logo, a little flying book, on a job board at the university’s career center and applied for a position at its Canadian book club division. Since 1948, Scholastic has sold books to students through catalogs and fliers distributed in schools, and one of Ms. Lucchese’s tasks in those early days was to help make the fliers given out in classrooms, sometimes with X-acto knife and glue in hand.

It was through her new job that she met Mr. Robinson in the early 1990s. Ms. Lucchese said she had been walking through the office on her way to the graphic art department with book club paste-ups in her arms when Mr. Robinson stopped her and asked what was listed in the fliers. Her work at Scholastic — and connection to Mr. Robinson — began at a time when fewer rules and guardrails existed around what a relationship with a superior could mean for the course of one’s career.

Early on, Ms. Lucchese tried to expand the range of books offered through the club, moving beyond classics to include more contemporary and commercial titles students would be eager to read. “You can try to push them to read the classics or what was your favorite,” she said, “but it’s really going uphill until that spark happens with a book that they love.”

She worked her way up through the Canadian book club division and then the Canadian corporate office, becoming a co-president. In the years that Ms. Lucchese worked in Canada, annual revenue grew to 150 million Canadian dollars from 25 million Canadian dollars, according to her biography on Scholastic’s website.

She was made the corporation’s chief strategic officer, then added executive vice president to her string of titles, charged with duties like streamlining areas of the business. To compensate her for her growing role, the board gave Ms. Lucchese a raise and a bonus in 2019, which brought her total compensation to nearly $1.2 million.

Around the time she moved to New York, Mr. Robinson bought an apartment for Ms. Lucchese’s use in the same building in which he was living, according to someone involved in the transaction who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the person was not authorized to speak to the news media.

Ms. Lucchese has focused much of her attention in recent years on her additional role as president of Scholastic Entertainment, pouring her time into film and television projects like “The Magic School Bus Rides Again,” a Netflix series in which the eager teacher Ms. Frizzle takes her students on magical scientific adventures to places like outer space or to the bottom of the sea.

The goal, Ms. Lucchese said, is to focus on a small number of quality productions that reflect the vision of Scholastic and its authors, in hopes of converting watchers into readers. “Ultimately, for us, it’s about selling the books,” she said.

It was while discussing these ventures that Ms. Lucchese was most animated, describing particular projects like the forthcoming movie “Clifford the Big Red Dog.” She gave a little cheer (“Yay!”) when she learned that a reporter’s children were fans of “The Magic School Bus Rides Again.”

“Clifford,” which was filmed before the pandemic, is scheduled to be released in theaters and on a streaming service in November. The adaptation places Clifford in New York City, away from his usual home on Birdwell Island. Jordan Kerner, one of the producers, said he had given Ms. Lucchese credit as a “producer” rather than the more ceremonial “executive producer” to reflect her day-to-day involvement.

“We were worried that Scholastic would react to Clifford being in New York, but she understood the comedy of it, of New Yorkers looking at their phones and not looking up at 10-foot dog,” said Mr. Kerner, who also produced the 2006 live-action “Charlotte’s Web” film and “The Smurfs.”

In the interview, Ms. Lucchese did seem to have thought quite a bit about how the big red dog would find life in the big city, and how he would adapt.

“Clifford is as big as a house if you read the books, but in order to make him interactable in the live-action movie, he has to fit in a room,” she said. “So he had to be a puppy.”

Since M. Richard Robinson Sr. founded the company in the sewing room of his parents’ house in Western Pennsylvania in 1920, Scholastic has been a family business. Dick Robinson’s siblings still own about 47 percent of the Class A shares, which are held by trusts.

Barbara Buckland, one of Mr. Robinson’s sisters, said the two of them often had dinner together on Sundays, though he would cancel if he was able to dine with his sons instead. She said he had come to her home for dinner shortly before he died and had been “full of his usual vim and vigor and all kinds of questions.”

“We’re saddened, but we know the company is in good hands,” said Ms. Buckland. “Nobody has any intention of selling. Nobody is worried. We are all sad.”

Despite Mr. Robinson’s age, his death came as a surprise to many in his personal and professional lives. A daily exerciser, he was fit and in full control of day-to-day operations at Scholastic, and anyone who knew him even a little bit would say the company was his life’s obsession.

A cartoon of his face, showing him looking off into the distance like a superhero, hangs on a gallery wall in Scholastic headquarters, near portraits of Harry Potter and Clifford. Ms. Lucchese said that when the office was redesigned a few years ago, Mr. Robinson hadn’t wanted any pictures of himself displayed but Ms. Lucchese said she sneaked that one in.

Mr. Robinson made it no secret that he wished Scholastic to remain an independent company, even as consolidation within the publishing business sped up around him. Penguin Random House, itself the product of a 2013 merger, is in the process of trying to buy Simon & Schuster. If approved by federal regulators, that deal would create a colossus far larger than any other publisher in the country.

But the remaining large houses will want to bulk up to compete, especially by acquiring rich “backlists,” catalogs of older titles that are reliable, long-term money makers — which is sure to make Scholastic an attractive target.

The company’s new leadership team appears to share what was perhaps Mr. Robinson’s most precious goal: Ms. Lucchese and Mr. Warwick expressed no interest in selling.

“We’ve got the resources ourselves to go forward at the pace that we want to go,” Mr. Warwick said.

Given Mr. Robinson’s devotion to Scholastic, it was fitting that his memorial service was held there last month. A virtual event with just a few people in attendance, it included a video eulogy delivered by his son Reece. “We will cherish the memories of the holidays and weekends we spent with him during Covid when he wasn’t working 12-hour days,” Reece Robinson said of his family’s relationship with his father.

The service had all the star power of a Hollywood collaboration, with video messages from Goldie Hawn, Bill Clinton and J.K. Rowling punctuating remarks from former employees and board members. The final speaker, Alec Baldwin, described the friendship he had developed with Mr. Robinson as neighbors in a downtown apartment building and expressed his condolences to Mr. Robinson’s family, the Scholastic community and Ms. Lucchese. He was the only speaker who mentioned her name.

Mr. Wallack, the portfolio manager for the company’s second-largest shareholder, had twice contacted investor relations at Scholastic to request information about Mr. Robinson’s funeral, he said. But no one alerted him to the memorial service, he said. “I was hopeful to have been invited to that,” he said, or at least sent a link. (In response, a company spokeswoman said the event was publicized on social media and the company’s website.)

Ms. Lucchese, one of Mr. Robinson’s closest business associates and the woman in control of the company, chose not to deliver remarks herself. Instead, she wrote a note in the program that appeared under a picture of Mr. Robinson’s broad smile.

“Dick knew that Scholastic could uniquely empower children to overcome obstacles,” she wrote. “He knew this work was worth doing, and he inspired in all of us the passion to get it done.”

The message was signed, “Iole Lucchese, Chair of the Board.”

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.

Katie Rosman is a features reporter who covers a range of topics including media and celebrity. She joined the Times in 2014. @katierosman

Elizabeth A. Harris writes about books and publishing. @Liz_A_Harris

ARTICLE By Katherine Rosman and Elizabeth A. Harris

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/18/business/scholastic-iole-lucchese-succession-battle.html

This week, the winner of the Planeta Prize, a Spanish 1-million-euro literary award, was announced: Carmen Mola, a famously private crime thriller writer. All that was known about Mola, often referred to as Spain’s “Elena Ferrante,” is that she was a university professor in her mid-40s living in Madrid with her husband and three children; three years ago, she told Spanish newspaper ABC that she used a pseudonym so as not to disrupt “an already-formed life that has nothing to do with literature.” But at the Planeta awards ceremony, the real reason for the pseudonym was revealed: Carmen Mola doesn’t exist. Instead, she is the product of three male screenwriters—Agustín Martinez, Jorge Díaz and Antonio Mercero—who showed up in person to pick up their prize money. According to The Guardian, their credits include television shows Central Hospital and Blind Date.

Some readers were irritated by the idea that the three men had used a woman’s persona to market their crime novels. Most of Carmen Mola’s novels center around detective Elena Blanco, a “peculiar and lonely woman, lover of grappa, karaoke, classic cars and SUV sex.” (The book that won the Planeta is not a Blanco novel; it centers around the search for a serial killer dismembering girls during an 1800s cholera epidemic.) Spanish newspaper El Mundo noted the Carmen Mola identity’s role in drumming up publicity: “It hasn’t escaped anyone’s notice that the idea of a high school teacher mother of three children who teaches algebra in the morning and in the afternoons, then writes novels of ultra-savage and macabre violence in her spare time, is a good marketing operation.”

Beatriz Gimeno, former head of the Women’s Institute in Spain, critiqued the trio on Twitter: “Beyond the use of a female pseudonym, these guys have been answering interviews for years. It is not only the name, it is the false profile with which they have scammed readers and journalists. Scammers.” (Last year, a regional branch of the Women’s Institute recommended Mola’s novel La Nena (The Girl) on a list of work by female authors that help readers “understand the reality and experiences of women at different times [in history] and make people aware of their rights and freedoms.”)

Twitter user Jenne Popay, responding to The Guardian’s coverage of the hoax, wrote, “Men use a woman’s persona—not just a name—to sell novels about extreme violence often against women & in the case of this prize dismembered girls! And they are awarded a prize?”

For their part, Martinez, Díaz and Mercero deny that their choice of a female pseudonym was calculated. “Choosing a woman’s name was not a thought-out thing,” Diaz told El Mundo. “We didn’t want to send any message. We could have put R2-D2 on it, but we named it Carmen Mola.”

“There is something very healthy in eliminating this obsession with the author, to know who they are, how they dress, what life they have,” Martinez added. “If Carmen Mola has worked it is because the readers have liked the stories. Getting rid of the ego is difficult, but we try to leave it out of the room. Deep down, we do not matter so much.”

ARTICLE By Walker Caplan

https://lithub.com/a-woman-won-a-million-euro-writing-prize-then-turned-out-to-be-three-men/

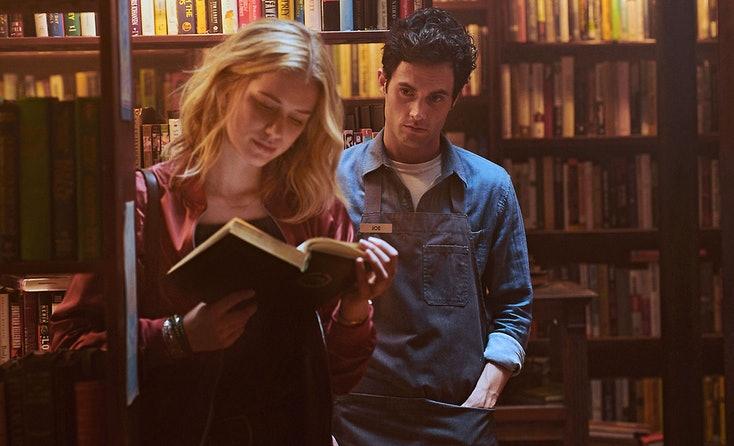

I AM HAUNTED BY JOE'S STUPID LITTLE BOOKSELLING APRON

...

The truth is that it is rare to be idle working in a bookstore, let alone stay romantic about it. Someone leaves a used tissue on the handrail, folded over and tucked onto itself like a diseased cravat. UPS just delivered a ton of shipments and half of them are either torn open or full of titles you didn’t order. The book that you love that you constantly try to push on customers hasn’t moved off the shelf in weeks. Meanwhile, you have to check if there’s any backstock of The Alchemist because, for some reason, we’re always selling out of The Alchemist. And The Four Agreements. And The Myth of Sisyphus. And, weirdly, the fifth My Struggle book (just the fifth one).

Obviously this wouldn’t make for very compelling TV, which is fine. Viewers prefer to see Penn Badgley, with his handsome, sculpted face, and his insane, incomprehensible apron idly put a few books on a shelf or ring up the odd tourist. But it irks me to no end. If anyone has to pop out it’s for some light stalking, not a run to the bank. No one is lifting heavy pieces of furniture or rearranging shelves. No one ships out orders. No one sets up book displays. No one even orders their books. At one point in You, Joe is shown opening a box of books that seem to have been teleported to him by God before putting them out directly onto the shelves. Questions abound. Why is there only one box? Why isn’t he drowning under the weight of at least ten more? Doesn’t he want to at least label the merchandise first?

Onscreen booksellers should, at the very least, be tired. Or stressed out, or pissed off, or shown to be doing something that they don’t have time for. Toilets have to be cleaned. There’s an old man on Line 1 who wants to know why we don’t sell a book that he can’t recall the title of but remembers seeing in a window once in 1998. That part in You’ve Got Mail when Tom Hanks’ Joe Fox shops at Kathleen Kelly’s store and balks at the full price? Yeah, that part, always, forever. Skull-face Bookseller Honda-san, a manga and anime featuring Japanese booksellers wearing armored helmets and plague doctor masks, is perhaps the only truly accurate depiction of bookstore life. Customer interactions are stressful, everything breaks, everything is heavy, there’s no room to put books out, there’s both too much and not enough time.The only trope more common than the perfect little bookstore is the bookstore that’s about to go out of business. People wearing shirts that say something like “My life is better with books” remind you that this book, every book, is much cheaper on am*zon and that e-readers are more convenient. All this can make a bookseller (me, I’m the bookseller) mean, which is why there is something recognizably funny and a little awful about people like Joe from You or Bernard Black from the British sitcom Black Books, who owns and runs the titular shop. Joe lords his pretentious literary authority over strangers. “These books are more alive, more worthy than anyone I know,” he says, the world’s most inept serial killer, television’s most negligent bookstore manager. Meanwhile, Bernard is constantly trying to get people out of his store. In one episode, a customer walks in during business hours and Bernard screams to his coworker, “Why didn’t you lock the door?!”

...Something about books, or the way we talk about books, stuns people into an obnoxious reverence about all the places that sell or borrow them. As my friend, who used to be a librarian and is now a best-selling author, told me recently, “Working in a library is like working in a coffee shop and by that I mean people don’t see you until they need something from you and then they ask for a sip from your mug.”In every Instagram photo of a perfectly sunlit stack of books labeled “a good bookstore is my happy place” there is someone who is extremely undercompensated just out of frame waiting to reshelve those titles they used for props. Bernard Black says, “The pay is not great, but the work is hard.” Sometimes you meet cool people, sometimes you get to push a book into someone’s hands that changes their life for a little while. You’ll likely never know if or how. You’ll likely not have a fulfilling interaction like that for many weeks or months! Then again, there’s always more work to do. Like explain to people that the new James Bond isn’t based on a novel or why we don’t have an edition of Dune with Timothee Chalamet’s face on it.

Nicholas Russell is a writer from Las Vegas. His work has been featured in The Believer, Defector, Reverse Shot, Vulture, The Guardian, NPR Music, and The Point, among other publications.

ARTICLE from NICHOLAS RUSSELL

https://www.gawker.com/culture/why-did-joe-from-you-wear-an-apron-to-sell-books"Imposing a minimum shipping cost for books would weigh on the purchasing power of consumers," am*zon told Reuters in a statement.

That is an undesirable consequence government officials are wary of at a time President Emmanuel Macron administration is scrambling to head off growing discontent over rising energy prices six months from an election.

More than 20% of the 435 million books sold in France in 2019 were bought online and the market share of France's 3,300 independent bookstores has been slowly declining because of competition from online retailers like am*zon, Fnac (FNAC.PA) and Leclerc.

French law prohibits free book deliveries but am*zon has circumvented this by charging a single centime (cent). Local book stores typically charge about 5-7 euros ($5.82-8.15) for shipping a book.

"This law is necessary to regulate the distorted competition within online book sales and prevent the inevitable monopoly that will emerge if the status quo persists," the ministry told Reuters.

Virtually-free delivery allowed book lovers in rural areas to buy books at the same price as someone who could walk into a bookstore -- precisely the spirit of the 1981 law, it said.

ARTICLE By Elizabeth Pineau

https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/france-moves-shield-its-book-industry-am*zon-2021-10-25/

REFERRING ARTICLE

https://kobowritinglife.com/2021/10/29/saving-french-indies-a-new-fsg-president-and-old-book-smell-this-week-in-book-news/

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)