-

Posts

3,909 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

120

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

MY THOUGHTS to Alice 2022

First to history,

Mae Louise Walls Miller is the name of the Black woman whose life, in my opinion, was a prime source to the research from Antoinette Harrell, who spanned many Black individuals in slavery or criminal bondage. I must say that first as the authors or content creators to many, most I viewed or read, articles/videos about the alice 2022 film didn't seem able to mention the Black woman in question, whose real life story inspired the video fable or the black woman who researched her.

The story of Miller, in the articles below in more detail, displays one of the large problems when we assess usa history. Most problems in the USA are publicly known, but financial profit or fear blockade any action. The White community profited from black enslavement before or after the 13th amendment, and thus white individuals or groups were against opposed in any form, including merely speaking, to stand against abuses to blacks from the white community.Second to the law

Like mandates, proclamations are not laws in the usa legal system. Proclamations are public announcements by the government. Mandates are public orders by the government. Proclamations or mandates by default are contestable in a court of law as they are not laws. The 13th amendment is a law, and it ended slavery throughout the entirety of the usa but the penal system.

I quote:

"Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

Sequentially, the emanicpation proclamation has to stop being referred to as the moment slavery ended. From a legal standpoint, slavery has never ended, so black people saying it has is not being honest to the situation of the black community in the usa.Third to the video fable,

I keep hearing Donny Hathaway's to be young gifted and black in my head, when I see Common. Am I wrong?

Many of the articles seem focused on suggesting this as a faux history, when I see more of a Black film fiction circa 2000. For me the story of this film of a black women who thinks she is in the 1800s but is in truth, 1960s is clearly modern Black horror in the space of Get Out or US.

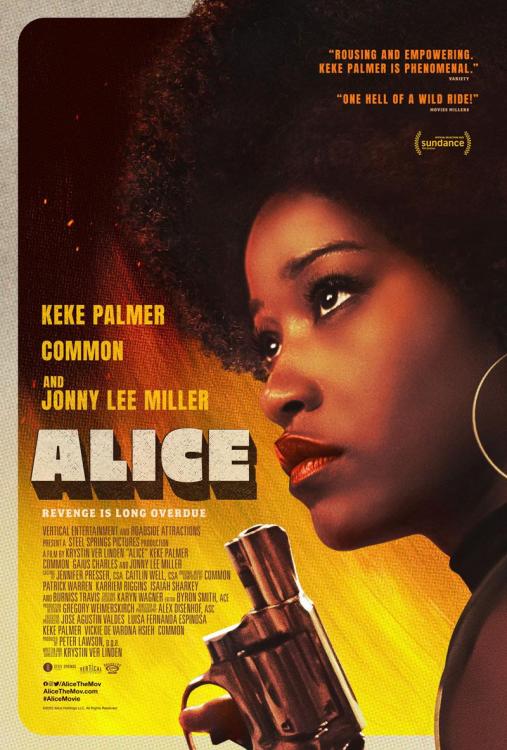

The poster and the words of the director clearly show this is a movie worthy of the roles Pam Grier played in the 1970s. A good revenge romp for fans of that genre or those with a penchant for black heroes in film.ALice 2022

written and directed by Krystin Ver Linden

Keke Palmer as Alice

Jonny Lee Miller as Paul Bennet

Common as Frank

Gaius Charles as Joseph

Alicia Witt as RachelARTICLES

TITLE: Black People in the US Were Enslaved Well into the 1960s

AUTHOR(S):Antoinette Harrell , at told to Justin Fornal

TIME OF PUBLISH: February 28, 2018, 12:00am

CONTENT:

More than 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, there were black people in the Deep South who had no idea they were free. These people were forced to work, violently tortured, and raped.Historian and genealogist Antoinette Harrell has uncovered cases of African Americans still living as slaves 100 years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. The 57-year-old Louisiana native has dedicated more than 20 years to peonage research. Through her work, she's unearthed painful stories in Southern states like Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Florida. Over a series of interviews, she told Justin Fornal about how she became an expert of modern slavery in the United States.

My mother always talked to me about our family history and the family members who had passed on. She only knew so many stories, so oftentimes she would tell the same ones over and over again. Each time she repeated a story, I felt like she was trying to give me a message. It was like she was trying to tell me that if I wanted to know more about who we were, I would have to dig deeper.

We knew our family had once been slaves in Louisiana. In 1994, I started to look into historical records and public records. I found my ancestors in the 1853 inventory belonging to Benjamin and Celia Bankston Richardson. Written down alongside other personal belongings that included spoons, forks, hogs, cows, and a sofa were my great great grandparents, Thomas and Carrie Richardson.

Carrie and her child Thomas had been appraised at $1,100. Seeing my ancestor’s perceived value written on a piece of paper changed me. It also set forth the direction of my life. It was terribly painful, but I needed to know more. What did they do after Emancipation in 1863? Where did they go? I tracked down Freedmen contracts of the Harrell side of my family that proved that they were sharecroppers. Word started spreading around New Orleans about how I was using genealogy to connect the dots of a lost history. Soon enough people started requesting that I come and speak about how I was uncovering my family’s story so they could do the same for themselves. It became a chance to find out who we were and where we came from as descendants of enslaved people. This was a chance to learn a history we were never taught in school.

The only fact that seemed certain was that slavery ended with the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. But even that turned out to be less than true.

One day a woman familiar with my work approached me and said, “Antoinette, I know a group of people who didn’t receive their freedom until the 1950s.” She had me over to her house where I met about 20 people, all who had worked on the Waterford Plantation in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana. They told me they had worked the fields for most of their lives. One way or another, they had become indebted to the plantation’s owner and were not allowed to leave the property. This situation had them living their lives as 20th-century slaves. At the end of the harvest, when they tried to settle up with the owner, they were always told they didn't make it into the black and to try again next year. Every passing year, the workers fell deeper and deeper in debt. Some of those folks were tied to that land into the 1960s.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Most shocking of all was their fear. I saw time and time again, people were afraid to share their stories. They were afraid to give this information to me, even behind closed doors decades later. They believed that they might somehow get sent back to a plantation that wasn’t even operating anymore. As I would realize, people are afraid to share their stories, because in the South so many of the same white families who owned these plantations are still running local government and big businesses. They still hold the power. So the poor and disenfranchised really don’t have anywhere to share these injustices without fearing major repercussions. To most folks, it just isn’t worth the risk. So, sadly, most situations of this sort go unreported.

Six months after that meeting, I was giving a lecture on genealogy and reparations in Amite, Louisiana, when I met Mae Louise Walls Miller. Mae walked in after the lecture was over, demanding to speak with me. She walked up, looked me in the eye, and stated, “I didn’t get my freedom until 1963.”

Mae's father, Cain Wall, lost his land by signing a contract he couldn’t read that had sealed his entire family’s fate. As a young girl, Mae didn’t know that her family’s situation was different from anyone else’s. The family didn’t have TV, so Mae just assumed everyone lived the same way her brothers and sisters did. They were not permitted to leave the land and were subject to regular beatings from the land owners. When Mae got a bit older, she would be told to come up to work in the main house with her mother. Here she would be raped by whatever men were present. Most times she and her mother were raped simultaneously alongside each other.

Her father, Cain, couldn’t take the suffering anymore and tried to flee the property by himself in the middle of the night. His plan was to register for the army and get stationed far away. But he was picked up by some folks claiming they would help him. Instead, they took him right back to the farm, where he was brutally beaten in front of his family.

When Mae was about 14, she decided she would no longer go up to the house. Her family pleaded with her as the punishment would come down on all of them. Mae refused and sassed the farm owner’s wife when she told her to work. Worrying that Mae would be killed by the owners, Cain beat his own daughter bloody in hopes of saving her. That evening still covered in blood, Mae ran away through the woods. She was hiding in the bushes by the road when a family rode by with their mule cart. The lady on the cart saw the bush moving. She got off to find Mae crying, bloodied and terrified. That white family took her in and rescued the rest of the Wall’s later that night.

These stories are more common than you think. There were also Polish, Hungarian, and Italian immigrants, as well other nationalities, who got caught up in these situations in the American South. But the vast majority of 20th-century slaves were of African descent.

When I met Mae, her father Cain was still alive. He was 107 years old, but his mind was still incredibly sharp. A few times we sat together with Mae and the other siblings. It was a brutal catharsis for them to speak about what happened on that farm. I’ll never forget the look in their eyes when one would speak about a horror they endured. It was clear they had never shared their individual stories with one another. It was something that was in the past so there was never a reason to bring it up. One day Cain was watching the television, and there was a Caucasian man with stark white hair on the program. The way he looked must have reminded Cain of someone from the farm. Cain believed that because he had told me what happened on the farm that the man on the TV was going to come to his house and drag him back. Opening the suppressed memories upset him so much he ended up in the hospital. The family kept me away for a while after that.

But Mae and I became good friends and would lecture together. There were unusual ticks she had from her upbringing. Sometimes, when we would be at an event where there was free food, she couldn’t stop eating. She told me this was from years of not knowing when she would eat again. There were other times she would need to take her shoes off. She had grown up not wearing shoes and said sometimes her feet felt uncomfortable when she wore them. The nuances of Mae’s PTSD from growing up as a slave gave me a look into what life must have been like for many of our ancestors who were held under such inhumane conditions.

Mae died in 2014. She was a fearless beautiful spirit and has left a gigantic void. I am glad her brother Arthur is continuing to tell the Wall’s family story. People who hear these stories will often say, “You should have gone to the police.” “You should have run sooner.” But the land down here goes on forever. These plantations are a country unto themselves. The property goes from can't see to to can't see. Even if you could run, where would you go? Who would you go to?

Do I believe Mae’s family was the last to be freed? No. Slavery will continue to redefine itself for African Americans for years to come. The school to prison pipeline and private penitentiaries are just a few of the new ways to guarantee that black people provide free labor for the system at large. However, I also believe there are still African families who are tied to Southern farms in the most antebellum sense of speaking. If we don’t investigate and bring to light how slavery quietly continued, it could happen again.

There were several times when I returned to the property where Mae and her family were held. There isn’t much there anymore in terms of the farm.

One day I walked with Mae deep into the woods to see the old green creek she always spoke about. That filthy patch of water where the cows pissed and shit was the same water that Mae and her family drank and bathed in. As we stood together looking into the water Mae’s words were forever seared into my soul.

“I told you my story because I have no fear in my heart. What can any living person do to me? There is nothing that can be done to me that hasn’t already been done.”U.R.L.: https://www.vice.com/en/article/437573/blacks-were-enslaved-well-into-the-1960s

TITLE: The enslaved black people of the 1960s who did not know slavery had ended

AUTHOR: ISMAIL AKWEI

CONTENT:

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 which changed the status of over 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the South from slave to free, did not emancipate some hundreds who were slaves through to the 1960s.

This was revealed by historian and genealogist Antoinette Harrell who unearthed shocking stories of slaves in Southern states like Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Florida over hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

She told Justin Fornal that her 1994 journey of historical truth revealed the stories of many 20th century slaves who came forth in New Orleans when they heard that she was using genealogy to connect the dots of a lost history.

She said a woman introduced her to about 20 people who had worked on the Waterford Plantation in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, as slaves until the 1960s.

“One way or another, they had become indebted to the plantation’s owner and were not allowed to leave the property … At the end of the harvest, when they tried to settle up with the owner, they were always told they didn’t make it into the black and to try again next year. Every passing year, the workers fell deeper and deeper in debt,” she said.

Many of them were afraid to share their stories as they believed they will be sent back to the plantation which isn’t even in operation. “People are afraid to share their stories, because in the South so many of the same white families who owned these plantations are still running local government and big businesses. They still hold the power.

“So the poor and disenfranchised really don’t have anywhere to share these injustices without fearing major repercussions. To most folks, it just isn’t worth the risk. So, sadly, most situations of this sort go unreported,” she told Justin Fornal and was published in art and culture magazine website Vice.

One of the 20th-century slaves was Mae Louise Walls Miller and she didn’t get her freedom until 1963. Her father, Cain Wall, lost his land by signing a contract he couldn’t read that enslaved his entire family.

They were not permitted to leave the land and the owners subjected them to beatings and rape. Mae and her mother were most times raped simultaneously alongside each other by white men when they go to the main house to work.

According to Harrell’s narration, Mae and her family did not know what was happening outside the land as they had no TV. Her father tried to flee the property, but was caught by other landowners who returned him to the farm where he was brutally beaten in front of his family.

When Harrell met Mae, her father was alive and he was 107 years old with a sharp memory. He beat Mae when she was 14 for attempting to flee the farm, an action whose consequence was beating of the entire family.

Mae, covered in blood, still run into the woods in the evening and hid in the bushes where a white family took her in and rescued the rest of her family later that night.

Harrell said the family suffered from PTSD as a result of their experiences. Mae died in 2014.

“I told you my story because I have no fear in my heart. What can any living person do to me? There is nothing that can be done to me that hasn’t already been done,” Mae told Harrell when they visited the property she and her family were held.

Antoinette Harrell believes “there are still African families who are tied to Southern farms in the most antebellum sense of speaking. If we don’t investigate and bring to light how slavery quietly continued, it could happen again.”

< https://video.vice.com/en_us/video/vice-the-slavery-detective-of-the-south/5a947b9cf1cdb3764f3eee86?jwsource=cl >

URL: https://face2faceafrica.com/article/the-enslaved-black-people-of-the-1960s-who-did-not-know-slavery-had-endedTITLE: Made in Frame: Inside Krystin Ver Linden’s Fiery Sundance Debut, “Alice”

AUTHOR: Lisa McNamara

CONTENT:

Utilize the link for the content, but the videos are placed immediately below< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHqrOSTIovU >

< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OibZx09HYAA>

U.R.L. : https://blog.frame.io/2022/02/14/sundance-alice-krystin-ver-linden/

TITLE: Keke Palmer to Star in True-Story Thriller ‘Alice’

AUTHOR: Chris Gardner

CONTENT: Utilize the url below to read but I placed an image of Keke palmer

TITLE: ALICE (2022) Movie Trailer: Keke Palmer Escapes from Jonny Lee Miller’s Plantation in Krystin Ver Linden’s Film

AUTHOR: ROllo Tomasi

CONTENT: Utilize the url below to read the article, I placed the trailer and movie poster beneath.

< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5CHq89MPnE >

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)