-

Posts

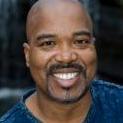

3,840 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

119

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

Haruhiko Kuroda, the Bank of Japan’s governor and the architect of its current policies.Credit...Richard A. Brooks/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Why Japan’s Sudden Shift on Bond Purchases Dealt a Global Jolt

The world has relied on ultralow interest rates in Japan. What will happen if they rise?By Ben Dooley

Reporting from TokyoJan. 3, 2023

Japan is the world’s largest creditor. At the end of 2021, it held roughly $3.2 trillion in foreign assets, 30 percent more than No. 2 Germany. As of October, it owned over a trillion dollars of U.S. government debt, more than China. Japanese banks are the world’s largest cross-border lenders, with nearly $4.8 trillion in claims in other countries.Late last month, the world got an unexpected reminder of how integral Japan is to the global economy, when the country’s central bank unexpectedly announced that it was adjusting its stance on bond purchases.

To those unversed in the intricacies of monetary policy, the significance of Japan’s decision to raise the ceiling on its 10-year bond yields may not have been immediately clear. But for the finance industry, the surprising change raised expectations that the days of rock-bottom Japanese interest rates could be numbered — potentially further squeezing global credit markets that were already tightening as the world economy slowed.

Since this summer, the Bank of Japan has been an outlier, keeping its interest rates ultralow even as other central banks raced to keep up with the Federal Reserve, which has ratcheted up lending costs in an effort to tame high inflation.

As global rates have diverged from those in Japan, the value of the yen has fallen as investors sought better returns elsewhere. That has put pressure on the Bank of Japan to shift the world’s third-largest economy away from its decade-long commitment to cheap money, a policy known as monetary easing.

Japan’s deep integration into global financial networks means that there is a lot of money riding on the timing of any move away from that policy, and investors have spent years fruitlessly waiting for a sign.

As of mid-December, the overwhelming expectation was that the bank would hold off on any changes until spring, when Haruhiko Kuroda, the Bank of Japan’s governor and an architect of its current policies, is set to step down.

So when the bank made its bond yield announcement, which effectively raised interest rates, it caught virtually everyone off guard.

Mr. Kuroda has been adamant that the decision does not represent a fundamental change in monetary policy. He has insisted that it was intended to encourage trading in 10-year bonds — the bank’s preferred tool for controlling interest rates — which had slowed to a trickle under the bank’s tight controls.

But markets, at least in the short term, weren’t convinced. After the announcement, global stock markets dropped. The yen surged more than 3 percent. And bond yields shot up.

No one, perhaps not even Mr. Kuroda, knows what the bank will do next, said Paul Sheard, a former chief economist of S&P Global. But among some market participants there’s a belief that “when a central bank makes one move, a lot more are coming,” he said.

For “the median investor in the world who’s looking at Japan out of the corner of their eye,” he said, “suddenly you see something that looks like the first move in what could be monetary tightening. That’s like a game changer.”

To understand why, we have to go all the way back to 2013, when Shinzo Abe, then a newly elected prime minister, proposed aggressive policies intended to shock Japan’s economy out of its decades-long torpor.

The most important piece of his strategy was a monetary policy intended to make it easier and more attractive for companies and households to borrow money and spend it.

Among other things, Mr. Abe and his team aimed to push inflation up to 2 percent. Japanese prices had languished for decades: The cost of fried chicken at one convenience store chain hadn’t gone up since the 1980s. While that might seem good for consumers, economists argued that it inhibited companies’ growth, which, in turn, made them reluctant to raise wages.

A modest increase in inflation could break that stasis, they believed, creating a virtuous cycle of rising prices, increased corporate profits and higher wages.

The Bank of Japan told everyone who would listen that it would do whatever it took to achieve its goal of stable price increases. The message was clear: It’s better to spend now, while things are still cheap.

To prove it meant business, the bank started purchasing vast sums of equities and bonds, spending so much that it doubled the amount of currency in the economy in less than two years. (At its peak, in May of last year, it had grown over five times.)

Central banks following a conventional monetary policy tend to focus on controlling short-term interest rates and let markets determine long-term rates. But in 2016 — with inflation still dormant — Japan decided to attempt something very unusual: It would seek to directly control some longer-term rates as well, using an untested policy called “yield curve control.”

Financial institutions base their interest rates, whether on a bank loan or a corporate bond, in part on the expected yields from government bonds. Reducing the market’s role in determining the prices of those bonds, the Bank of Japan figured, would let it better control lending conditions.

The mechanism for accomplishing that depended on one of a bond’s most fundamental attributes: Its price and yield move in opposite directions. The lifetime value of a bond is fixed on the day it’s issued, so if you pay more for it, your returns — the yield — go down. If you pay less, they go up.

When the Bank of Japan introduced its new policy, it committed to buying as many bonds as necessary at whatever price was required to keep yields around zero percent on the 10-year bond, the benchmark for other rates.

Things didn’t quite go as planned.

Rates stayed low, and inflation did, in recent months, hit the 2 percent benchmark. But it kept climbing, reaching 3.7 percent in November, a 40-year high. And most of that wasn’t the good, wage-boosting, demand-driven inflation the Bank of Japan wanted. It was “bad” inflation created by supply shortages from the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

What’s more, the growing gap between interest rates in Japan and elsewhere was pushing down the yen’s value, piling even more stress on the country’s highly import-dependent economy. That made some analysts speculate that the Bank of Japan would soon be forced to raise interest rates.

Which brings us up to December, when Mr. Kuroda suddenly announced that the bank would double the ceiling on 10-year bond yields, allowing them to fluctuate between plus and minus 0.5 percent, and effectively raising interest rates.

To many investors, the decision seemed like the first tentative step toward even bigger rate increases. As bond yields have jumped, the bank has had to spend heavily to defend its rate target.

Which raises the question, how much longer can the Bank of Japan stick to its guns?

The answer depends on a number of factors, including the performance of the global economy and whether the central bank feels it has finally reached its targets for wage growth and inflation, said Toshitaka Sekine, a professor of economics at Hitotsubashi University.

Most experts believe that the process of unwinding Mr. Kuroda’s monetary easing policy, when it happens, will take years. It is certain to be complicated: Many Japanese borrowers have become accustomed to cheap money — variable interest rates are common, for example — and a hasty retreat could strain households and firms alike.

It could also be painful for global markets that have come to take Japan’s loose monetary policy for granted. Years of anemic growth and a decade of superlow interest rates have pushed many Japanese investors to seek higher returns abroad, increasing their already prominent role in global credit markets.

Although unlikely, a rapid reversal by the Bank of Japan “could generate some hard-to-anticipate shock waves around the world,” said Brad Setser, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an expert on global trade and capital flows. “In the worst-case scenario, rapid rises in long-term Japanese rates push up long-term interest rates globally.”

Ben Dooley reports on Japan’s business and economy, with a special interest in social issues and the intersections between business and politics. @benjamindooley

MY THOUGHTS

One of the tragedies of the financial activity by the United States of America is the deterioration of the concept of debt.

Debt used to be a thing you were happy not to have. But the USA federal government has made debt a currency, a tool to control affairs in humanity.

The Japanese are owed over a trillion dollars, but they don't have the military to demand that money is given. Sequentially, all they can do is hold it or present it in financial schemes to others.

Japan decides to provide USA's debt to others as currency. Sequentially, governments throughout humanity buy USA's debt to Japan which Japan gets a financial percentage of sale from.

Personally, I will never buy anyone's debt nor will I buy what anyone else is owed. The USA military was already the most potent element in the usa through the cold war arms race, but the usa military has become switzeland in that it's existence allows the usa to keep producing debt, cause even with a unleavened debt ceiling what country can call in the usa's debt, especially a country absent a military like japan or germany.

Japan's near future will be very interestingThoughts to the japanese or japan in a forum post

comment1

https://aalbc.com/tc/topic/9982-70-japanese-organizations-wrote-president-biden-a-letter-to-give-african-americans-reparations-december-2022/?do=findComment&comment=57947Article URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/03/business/japan-bonds-interest-rates.html

Mr. Yokoyama plans to give away his land and equipment to a successor he has chosen.Credit...Noriko Hayashi for The New York TimesJapan’s business owners can’t find successors. This man gave his away.

By Ben Dooley and Hisako Ueno

Ben Dooley and Hisako Ueno traveled to Monbetsu, Japan, to report this story.Hidekazu Yokoyama has spent three decades building a thriving logistics business on Japan’s snowy northern island of Hokkaido, an area that provides much of the country’s milk.

Last year, he decided to give it all away.

It was a radical solution for a problem that has become increasingly common in Japan, the world’s grayest society. As the country’s birthrate has plummeted and its population has grown older, the average age of business owners has risen to around 62. Nearly 60 percent of the country’s businesses report that they have no plan for what comes next.

While Mr. Yokoyama, 73, felt too old to carry on much longer, quitting wasn’t an option: Too many farmers had come to depend on his company. “I definitely couldn’t abandon the business,” he said. But his children weren’t interested in running it. Neither were his employees. And few potential owners wanted to move to the remote, frozen north.

So he placed a notice with a service that helps small-business owners in far-flung locales find someone to take over. The advertised sale price: zero yen.

Mr. Yokoyama’s struggle symbolizes one of the most potentially devastating economic impacts of Japan’s aging society. It is inevitable that many small and medium-size companies will go out of business as the population shrinks, but policymakers fear that the country could be hit by a surge in closures as aging owners retire en masse.

In an apocalyptic 2019 presentation, Japan’s trade ministry projected that by 2025, around 630,000 profitable businesses could close up shop, costing the economy $165 billion and as many as 6.5 million jobs.

Economic growth is already anemic, and the Japanese authorities have sprung into action in hopes of averting a catastrophe. Government offices have embarked on public relations campaigns to educate aging owners about options for continuing their businesses beyond their retirements and have set up service centers to help them find buyers. To sweeten the pot, the authorities have introduced large subsidies and tax breaks for new owners.

Still, the challenges remain formidable. One of the biggest obstacles to finding a successor has been tradition, said Tsuneo Watanabe, a director of Nihon M&A Center, a company that specializes in finding buyers for valuable small and medium-size enterprises. The company, founded in 1991, has become enormously lucrative, recording $359 million in revenue in 2021.

But building that business has been a long process. In years past, small-business owners, particularly those who ran the country’s many decades- or even centuries-old companies, assumed that their children or a trusted employee would take over. They had no interest in selling their life’s work to a stranger, much less a competitor.

Mergers and acquisitions “weren’t well regarded,” Mr. Watanabe said. “A lot of people felt that it was better to shut the company down than sell it.” Perceptions of the industry have improved over the years, but there are “still many businesspeople who aren’t even aware that M.&A. is an option,” he added.

While the market has found buyers for the businesses most ripe for the picking, it can seem nearly impossible for many small but economically vital companies to find someone to take over.

In 2021, government help centers and the top five merger-and-acquisitions services found buyers for only 2,413 businesses, according to Japan’s trade ministry. Another 44,000 were abandoned. Over 55 percent of those were still profitable when they closed.

Many of those businesses were in small towns and cities, where the succession problem is a potentially existential threat. The collapse of a business, whether a major local employer or a village’s only grocery store, can make it even harder for those places to survive the constant attrition of aging populations and urban flight that is hollowing out the countryside.

After a government-run matching program failed to find someone to take over for Mr. Yokoyama, a bank suggested that he turn to Relay, a company based in Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island.

Relay has differentiated itself by appealing to potential buyers’ sense of community and purpose. Its listings, featuring beaming proprietors in front of sushi shops and bucolic fields, are engineered to appeal to harried urbanites dreaming of a different lifestyle.

The company’s task in Mr. Yokoyama’s case wasn’t easy. For most Japanese, the town where his business is situated, Monbetsu, which has around 20,000 people and is shrinking, might as well be the North Pole. The only industries are fishing and farming, and they largely go into hibernation as the days grow short and snow piles up to roof eaves. In deep winter, some tourists come to eat salmon roe and scallops and see the ice floes that lock in the city’s modest port.

A street full of 1980s-era cabarets and restaurants is a snapshot of a more prosperous time when young fishermen gathered to let off steam and spend big paychecks. Today, faded posters peel off abandoned storefronts. The town’s biggest building is a new hospital.

In 2001, Monbetsu constructed a new elementary school building just around the corner from Mr. Yokoyama’s company. It closed after just 10 years.

In times past, the classrooms would have been filled with the grandchildren of local dairy farmers. But their own children have now mostly moved to cities in search of higher-paying, less onerous work.

With no obvious successors, the farms have folded one after another. Decades-high inflation brought on by the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine has pushed dozens of holdouts into early retirement.

As local farmers have aged and their profits thinned, more of them have come to depend on Mr. Yokoyama for tasks like harvesting hay and clearing snow. His days start at 4 a.m. and end at 7 in the evening. He sleeps in a small room behind his office.

It would be “extremely difficult” if his business folded, said Isao Ikeno, the manager of a nearby dairy cooperative that has turned heavily to automation as workers have become harder to find.

On the cooperative’s farm, 17 employees tend to 3,000 head of cattle, and Mr. Yokoyama’s company fills in the gaps. No other area businesses can provide the services, Mr. Ikeno said.

Mr. Yokoyama began contemplating retirement about six years ago. But it wasn’t clear what would happen to the business.

While he had taken on a little over half a million dollars in debt, years of generous economic stimulus policies have kept interest rates at rock bottom, easing the burden, and the company’s annual profit margin was around 30 percent.

The ad he placed on Relay acknowledged that the job was hard, but it said that no experience was needed. The best candidate would be “young and ready to work.”

Whoever was chosen would take over the debts, but also inherit all of the business’s equipment and nearly 150 acres of prime farmland and forest. Mr. Yokoyama’s children will get nothing.

“I told them that if you want to take it over, I’d leave it to you, but if you don’t want to do it, I’m giving it all to the next guy,” he said.

Thirty inquiries poured in. Among those who expressed interest were a couple and a representative of a company that planned to expand. Mr. Yokoyama settled on a dark horse, 26-year-old Kai Fujisawa.

A friend had shown Mr. Fujisawa the ad on Relay, and Mr. Fujisawa immediately jumped in a car and showed up on Mr. Yokoyama’s doorstep, impressing him with his youth and enthusiasm.

Still, the transition hasn’t been smooth. Mr. Yokoyama is not entirely convinced that Mr. Fujisawa is the right person for the job. The learning curve is steeper than either of them had imagined, and Mr. Yokoyama’s grizzled, chain-smoking employees are skeptical that Mr. Fujisawa will be able to live up to the boss’s reputation.

Most of the company’s 17 employees are in their 50s and 60s, and it’s not clear where Mr. Fujisawa will find people to replace them as they retire.

“There’s a lot of pressure,” Mr. Fujisawa said. But “when I came here, I was prepared to do this for the rest of my life.”

Ben Dooley reports on Japan’s business and economy, with a special interest in social issues and the intersections between business and politics. @benjamindooley

Hisako Ueno has been reporting on Japanese politics, business, gender, labor and culture for The Times since 2012. She previously worked for the Tokyo bureau of The Los Angeles Times from 1999 to 2009. @hudidi1

MY THOUGHTS

Nippon's woes today is what happens when any government is created and uplifted by an enemy. I think about how Nippon was totally destroyed after the second phase of the world war. How Nippon was originally unsupported by the USA, but how the actions of the common folk flocking to socialistic forms and an anti usa zeal prompted the usa to use its imperial power to rebuild.

And it was brilliant to those who were in trouble, the culture in japan no longer needed to change, those who wanted change were killed or imprisoned or made sick or silenced in one way or the other by the usa military.

The business owners , many who fled Nippon were able to crawl back into Nippon and continue their culture or lifestyle unabated. The USA found in Nippon a totally militaristically impotent country, it made, that is a complete ally to the usa in government or financial affairs.

But... the problems are here. Nippon never learned to grow on its own after the war between the states. In the meiji era Nippon internally changed on nippon's terms and related to the outside humanity whose militaristic technology knocked down their walls. Now Nippon simply acted as a slave to the USA in nearly all matters. Buying USA's debt, hiring USA's workers, moving their factories to the USA, Nippon commonly called Japan became USA's bitch to use a common negative term.

And while many praise Japan, the price as the article above proves is clear.Article URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/03/business/japan-businesses-succession.html

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)