-

Posts

3,840 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

119

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

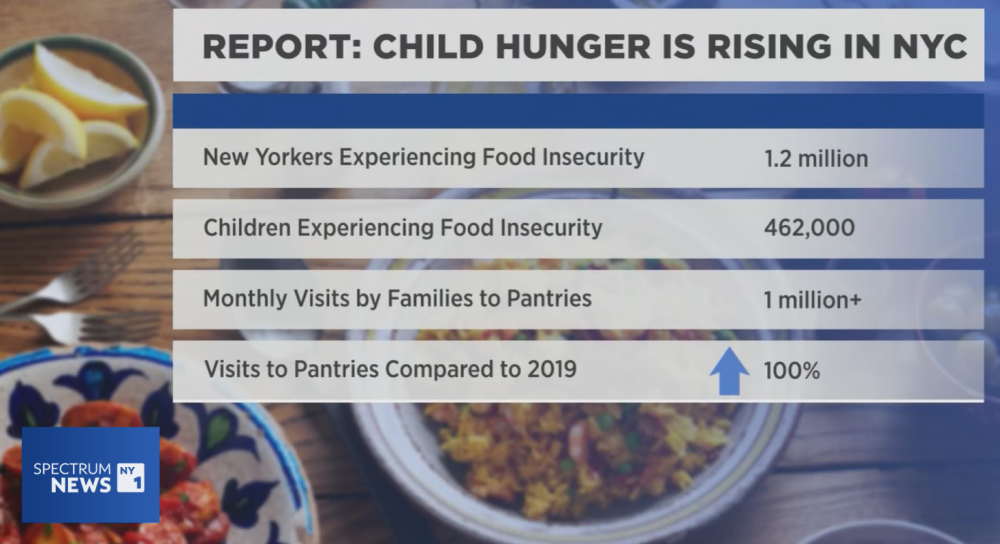

The problem here is language. When did hunger become a non usable word. Food insecurity means hunger, it isn't a slur or insult to call hunger what it is. Hunger isn't beyond the USA or foreign to the USA.

white people say NYC has circa 8,200,000 people. I say 10,000,000 but if 1,200,000 humans in NYC are hungry then that is 14.6 percent to 12 percent. so one out of every ten New Yorkers are hungry . Visits to pantries are up 100% which means hunger is growing. Now, I argue this is part of eric adams plan. Many people in the USA love to forgive the government for its injurious planning, while supporting the institution of law enforcement as a tool to keep the hungry from rioting.

The report shows a nearly 100% increase in visits to pantries by families with children, compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. (Spectrum News NY1)

Report: Child hunger rates continue to rise in New York City

By Rebecca Greenberg Brooklyn

PUBLISHED 8:40 PM ET May 28, 2024

A new report by City Harvest finds one in four children in New York City are experiencing food insecurity — a trend that continues to worsen since the COVID-19 pandemic.What You Need To Know

Last year, families made more than 1 million average monthly visits to food pantries in the city, according to a report by City HarvestThe report shows a nearly 100% increase in visits to pantries by families with children, compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic

Community Food Connection, which supplies high quality food to charities and food banks, could have its funding slashed by $30 million as part of Mayor Eric Adams’ preliminary executive budget for next year

Courtney Fields is among 1.2 million New Yorkers who don’t have enough to eat and don’t know where their next meal will come from.She said her nearest food pantry is a lifeline for herself and her five young children.

“It’s serious at the end of the month for single moms and I don’t know what I would do if the pantry wasn’t here. Honestly, I don’t,” Fields said.

Every week, the single mother walks one mile from her homeless shelter to the Bed-Stuy Campaign Against Hunger.

She said without this food pantry, her family would not survive.

“I’ll probably have to resort to things that I don’t want to resort to. Some people don’t have fathers for extra help. I don’t even have a father. I lost all the support. So it’s just me. I don’t know what I would do,” Fields said.

According to a new report by City Harvest, one in four children doesn’t have enough food to meet their nutritional needs. Last year, families made more than 1 million average monthly visits to food pantries in the city.

Data also shows a nearly 100% increase in visits to pantries by families with children compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jerome Nathaniel, who is the director of Policy and Government Relations for City Harvest, which published the child hunger report, said resources for low-income families have dwindled in the years following the pandemic.

“During COVID, there were a number of critical government programs and new food access programs that were put in place to support families and unfortunately, many of those programs have shored up or they’ve been allowed to sunset, leaving children without that support,” Nathaniel said.

Advocates for the hungry say the city should continue to invest in programs like Community Food Connection, or CFC, which supplies high-quality food to charities and food banks.

But Mayor Eric Adams’ preliminary executive budget for next year includes $30 million in cuts to that program.

“If Community Food Connection is cut, then chances are, we will have to cut from every end because they’re the ones supporting all our programs. We’re serving over 14,000 per week,” Melony Samuels, the CEO and founder of The Campaign Against Hunger, which has 250 locations across the five boroughs, said.

In a statement, a spokesperson for City Hall said, “The Adams administration continues to combat food insecurity in our city… We will continue to closely monitor ongoing needs through the budget process while simultaneously working with our city partners and key stakeholders to delivery for New Yorkers in need.”

Meanwhile, Fields hopes programs like The Campaign Against Hunger will continue to operate so she and her children can have a fighting chance.

“They’re gonna go hungry. So they need places like this so they can eat if someone like me doesn’t have support to feed the kids. We rely on places like this to feed the kids,” Fields said.

Adams still needs to negotiate a final budget with the City Council before the July 1 deadline.

URL

The average Electric vehicle in the USA is $52,000 , Chinese electric vehicles are being bought in Europe, dominating their market at a price of $10,000 . So Biden wants people in the usa to pay five times more for an electric vehicle made in the usa. Biden is denying the most affordable option available in the global market while trying to hope the domestic environment can provide an alternative. The simple arithmetic is clear, the global market for electric vehicles will be dominated by chinese automakers and the usa will be the one place where the chinese automakers don't dominate because of governmental tarrifs. Which the usa chagrined other countries do to protect their domestic markets.

The USA for years has benefited from cheap chinese goods. Manufacturers in the usa are too costly

and to be blunt, tend to be beneath acceptable quality when they sell something affordable to the masses. (https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/18/business/biden-china-tariffs.html)Biden Doesn’t Want You Buying an E.V. From China. Here’s Why.

The president wants to shift America’s car fleet toward electric vehicles, but not at the expense of American jobs or national security.

By Jim Tankersley

Reporting from WashingtonMay 27, 2024

President Biden wants more of America’s cars and trucks to run on electricity, not gas. His administration has pushed that goal on multiple fronts, including strict new regulations of auto emissions and lavish new subsidies to help American consumers take as much as $7,500 off the cost of a new electric vehicle.Mr. Biden’s aides agree that electric vehicles — which retail for more than $53,000 on average in the United States — would sell even faster here if they were less expensive. As it happens, there is a wave of new electric vehicles that are significantly cheaper than the ones customers can currently buy in the United States. They are proving extremely popular in Europe.

But the president and his team do not want Americans to buy these cheap cars, which retail elsewhere for as little as $10,000, because they are made in China. That’s true even though a surge of low-cost imported electric vehicles might help drive down car prices overall, potentially helping Mr. Biden in his re-election campaign at a time when inflation remains voters’ top economic concern.

Instead, the president is taking steps to make Chinese electric vehicles prohibitively expensive, in large part to protect American automakers. Mr. Biden signed an executive action earlier this month that quadruples tariffs on those cars to 100 percent.

Those tariffs will put many potential Chinese imports at a significant cost disadvantage to electric vehicles made in America. But some models, like the discount BYD Seagull, could still cost less than some American rivals even after tariffs, which is one reason Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and some other Democrats have called on Mr. Biden to ban Chinese E.V. imports entirely.The apparent clash between climate concerns and American manufacturing has upset some environmentalists and liberal economists, who say the country and the world would be better off if Mr. Biden welcomed the importation of low-cost, low-emission technologies to fight climate change.

Mr. Biden and his aides reject that critique. They say the president’s efforts to restrict Chinese electric cars and other clean-technology imports are an important counter to illegal and harmful trade practices being carried out by Beijing.

And they insist that Mr. Biden’s trade approach will ultimately benefit American jobs and national security — along with the planet.

Here are the policy and political considerations driving Mr. Biden’s attempt to shield American producers from Chinese competition.

Denying Beijing a new monopoly

China already dominates key clean-energy manufacturing in areas like solar cells and batteries. Mr. Biden’s aides want to prevent it from gaining monopolies in similar industries, like electric vehicles, for several reasons.They include climate concerns. Administration officials say Chinese factories, which tend to be powered by fossil fuels like coal, produce more greenhouse gas emissions than American plants.

There is also a central economic reason to deny China a monopoly: ensuring that electric cars and trucks will always be available, at competitive prices. The Covid-19 pandemic drove home the fragility of global supply chains, as critical products like semiconductors became hard to get from China and other Asian nations that the United States relied upon. Prices for consumer electronics and other products that relied on imported materials soared, fueling inflation.

Biden officials want to avoid a similar scenario for electric vehicles. Concentrating the supply of E.V.s and other advanced green tech in China would risk “the world’s collective ability to have access to the technologies we need to be successful in a clean energy economy,” said Ali Zaidi, Mr. Biden’s national climate adviser.

Shoring up national security

Biden officials say they are not trying to bring the world’s entire electric vehicle supply chain to the United States. They are cutting deals with allies to supply minerals for advanced batteries, for example, and encouraging countries in Europe and elsewhere to subsidize their own domestic clean-tech production. But they are particularly worried about the security implications of a major rival like China dominating the space.The administration has initiated investigations into the risks of software and hardware of future imported smart cars — electric or otherwise — from China that could track Americans’ locations and report back to Beijing. Liberal economists also worry about the prospect of China cutting off access to new cars or key components of them, for strategic purposes.

Allowing China to dominate E.V. production risks repeating the longstanding economic and security challenges of gasoline-powered cars, said Elizabeth Pancotti, the director of special initiatives at the liberal Roosevelt Institute in Washington, which has cheered Mr. Biden’s industrial policy efforts.

Americans have struggled for decades to cope with decisions by often hostile oil-producing nations, which act as part of the OPEC cartel, to curtail production and raise gasoline prices. China could wreak similar havoc on the electric-car market if it drives other nations out of the business, she said.

If that happens, she said, “reversing that is going to be really difficult.”

Biden needs the energy transition to create jobs

There is no denying that politics also play a huge factor in Mr. Biden’s decisions. Simply put: He is promising that his climate program will create jobs — good-paying, blue-collar manufacturing jobs, including in crucial swing states like Pennsylvania and Michigan.Mr. Biden is a staunch supporter of organized labor, and is counting on union votes to help win those states. He has pledged that the energy transition will boost union workers. He is betting their support for tariffs meant to protect American manufacturing jobs will dwarf any complaints from environmentalists who want faster progress on reducing emissions.

“One of the constituent groups in the Democratic Party that’s really highly organized, that gets people out to knock on doors, is the labor movement, more so than the environmental movement,” said Todd Vachon, a professor of labor studies at Rutgers University and the author of “Clean Air and Good Jobs: U.S. Labor and the Struggle for Climate Justice.”Those concerns have come into especially high relief given that many clean energy jobs are with young companies where workers aren’t unionized, he added.

Mr. Biden put those concerns front and center when announcing his tariff decision last week.

“Back in 2000, when cheap steel from China began to flood the market, U.S. steel towns across Pennsylvania and Ohio were hit hard,” he said at the White House. “Ironworkers and steelworkers in Pennsylvania and Ohio lost their jobs. I’m not going to let that happen again.”

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/business/biden-evs.htmlThe problem isn't the rule of the people, the problem is dysfunctional policy. One of the problems of the usa model is that dysfunctional policy works. This is based on the advertised success of the usa militaristically + financially. But the usa was and is a huge financial profiteer of centuries of mass enslavement. Remember most continental european countries enslavement was external, the cost of shipping and maintain the overseas military was a cost the european american did not have to deal with as its enslavement was local. Second the usa used immigration to strengthen its populace to maintain violent control over the enslaved+ eradicate or annihilate the indigenous or remaining indigenous. The funny thing is how a country like South Africa whose black populace have a majority in populace but are the lowest financial rung think a system by the usa or from white european heritage can work. Luckily for me south africa's change from apartheid to post apartheid is in my lifetime. I saw how south africa under mandela was guided to its current state. The USA was a jewel of white european imperialism that broke away from its motherland/Western European Countries were former global empires built up by the usa to stop them from joining Soviet russia/Russia has an untold level of natural resources and a military to protect itself/ japan was a former global empire rebuilt by the usa to stop them joining soviet russia/China is a country that found freedom from white domination, including that of the usa, during world war two and through a large populace+large natural resources+ a distrust of all foreigners including the usa became a world power. But South Africa was a country majority black whose majority population was taking a nonviolent approach to the minorities: whites/indians/coloreds who enjoyed their financial luxury while keeping the black majority under foot through violent means. Mandela gave this racial relationship, totally negative in structure, a legal fellowship that was and is totally absent. Blacks/colored/indians/whites are four different peoples, they can not fornicate into one people, nor do any of them want to. Mandela chose the wrong system, he should had did what china did, take some ideas from outside but make a system that relates to the situation of south africa specifically. China has a law that says no law from outside of china has superiority over chinese law in china. That stems from the fact that the usa/england/france/germany/russia/japan all had spheres of china as domains. The chinese learned no one can be trusted from their experiences. But the chinese also applied this after violence. Black South Africans need violence and then need to turn south africa into what they want, and if they want the coloreds/indians/whites around.

South Africa’s Young Democracy Leaves Its Young Voters Disillusioned

We spoke to South Africans who grew up in the three decades since the country overthrew apartheid and held its first free election about their lives and plans to vote — or not — in this week's pivotal election.By Lynsey ChutelPhotographs by Joao Silva

Reporting from Johannesburg, Polokwane, Carletonville, Phoenix and Gqeberha in South AfricaMay 28, 2024

At the dawn of South Africa’s democracy after the fall of the racist apartheid government, millions lined up before sunrise to cast their ballots in the country’s first free and fair election in 1994.Thirty years later, democracy has lost its luster for a new generation.

South Africa is now heading into a pivotal election on Wednesday, in which voters will determine which party — or alliance — will pick the president. But voter turnout has been dropping consistently in recent years. It fell to below 50 percent for the first time in the 2021 municipal elections, and analysts said that voter registration has not kept up with the growth of the voting-age population.

This downward curve has mirrored the support for South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress, or A.N.C., which was a liberation movement before becoming a political machine. Polls show the party may lose its outright majority for the first time since taking power in 1994 under the leadership of Nelson Mandela.

A new generation of voters do not have the lived experience of apartheid nor the emotional connection that their parents and grandparents had to the party. The A.N.C. as a governing party is all young people know, and they blame it for their joblessness, rampant crime and an economy blighted by electricity blackouts.

“Generational change or replacement has finally caught up with the A.N.C.,” said Collette Schulz-Herzenberg, an associate professor in political science at Stellenbosch University in South Africa.South Africa is no exception to global trends: Studies show that Gen Z and millennial voters in many countries have lost faith in the democratic process, even as they remain deeply concerned about issues like climate change and the economy.

But in South Africa, where the median age is 28, young people make up more than a quarter of registered voters in a population of 62 million, and are a crucial voting bloc. But only 4.4 million of the 11 million South Africans ages 20 to 29 have registered to vote in this election, according to statistics from South Africa’s Independent Electoral Commission.

The commission staged national campaigns to persuade more young people to register, and data show an encouraging uptick in registration of 18- and 19-year-olds who will vote for the first time in this election, to 27 percent from 19 percent since the last election.

But we spoke with many young people across the country who told us that they would sit out the election — a political rebuke to the A.N.C. and an indication that the country’s many opposition parties had failed to woo them.‘We are raising a generation of dependent young people’

Athenkosi Fani, 27His whole life, Athenkosi Fani has relied on the A.N.C. government, and he hates that feeling.

“I am made to depend on the system,” he said, sitting in his dorm room at Nelson Mandela University in the coastal city of Gqeberha, formerly known as Port Elizabeth. “We are raising a generation of dependent young people.”

Mr. Fani is a postgraduate student who has attended universities named for A.N.C. stalwarts, like Mr. Mandela and Walter Sisulu, but he said that staying in school was all that kept him from being yet another unemployed Black graduate.

He had a tragic childhood, worsened by the enduring poverty in Eastern Cape Province where he grew up. Mr. Fani’s mother received a social grant for him when he was born. Social grants, or welfare payments, are a lifeline for more than a third of households in South Africa — a state of affairs that A.N.C. politicians frequently remind voters about.

At age 11, Mr. Fani was placed in an orphanage when his mother could no longer care for him, and he became a ward of the state until 18. But he is gregarious and outspoken, and received a series of important boosts along his path.

To attend university, he relied on government financial aid. A provincial A.N.C. leader bought a laptop for him and paid for him to attend a monthlong traditional initiation for young men, an important rite of passage in the region. At his graduation in March, a member of the National Youth Development Agency attended, after it, too, funded him.

He has been an L.G.B.T.Q. activist since he was a teenager, and traveled to the United States to attend a Lion’s Club conference for young leaders to promote democracy. He was briefly an A.N.C. volunteer. All these experiences made him an ideal ambassador for youth issues, but also deeply resentful.He said that he grudgingly voted for the A.N.C. in the last election as a sign of gratitude. This time, he said, he is staying home on Election Day.

“I still do believe in democracy,” he said, but added, “I don’t want any organization that gets to have so much power.”

‘My vote isn’t going to count’

Shaylin Davids, 23Down deep, Shaylin Davids knows she’s part of the problem.

“The crime rate would actually go down if they start employing people,” said Ms. Davids, as she held court in her garage in Noordgesig, a township west of Johannesburg, with several friends. All are high school graduates, and all are unemployed.

Ms. Davids said she was good at school, but used her smarts to run drugs instead of attend university. An uncle she was close to was gunned down this past New Year’s Eve.

Aspiring now to turn a page, she started a computer course at a community center this year, hoping that it would land her a job if an employer looked past the tattoos on her face and fingers.

Ms. Davids’s grandmother told her that young people like her in her township actually had better prospects under apartheid. Ms. Davids is Coloured, the term still used for multiracial South Africans, who make up just over 8 percent of the population. Under apartheid, Coloured South Africans had better access than Black South Africans to jobs in factories and the trades.

Like many other Coloured South Africans, Ms. Davids feels left behind by a majority-Black government, and blames the A.N.C.’s affirmative action policies, which favored Black people, for reducing her job opportunities. This sentiment endures despite the reality that the unemployment rate for Black South Africans is 37 percent, compared with 23 percent for Coloured people in the country. But it has been enough to grow support for ethnically driven political parties.

Ms. Davids, though, is not interested in their slogans. She doesn’t follow politics, but she does follow the news. She watched bits of the finance minister’s budget speech in February, and concluded that he understood nothing about the cost-of-living crisis choking her neighborhood or how insufficient the social grant is.

Misinformation is rife, and she and her friends have heard rumors that if they registered, their votes would automatically go to the A.N.C. And even without that, she can’t see how her vote would change the country.

“I don’t want to vote because my vote isn’t going to count,” she said. “At the end of the day, the ruling party is still going to be A.N.C. There’s still no change.”

‘It’s not as good as it could be’

Aphelele Vavi, 22High school was great for Aphelele Vavi. His teachers were “superstars,” he said; the cafeteria had great snacks; and it is where he discovered his love of audiovisual production, which he is now turning into a career.

Mr. Vavi spent his teens ensconced in the bubble of a Johannesburg private school, and the friends and connections he made continue to shape his network and his prospects.

He lives in Sandton, a cluster of wealthy suburbs in northern Johannesburg, the son of a prominent trade unionist — making him part of the Black elite. But he was also exposed to the harsh realities of less-privileged South Africans, like his cousins, who still live in rural Eastern Cape Province.He said of post-apartheid South Africa: “It’s been really good to me.”

A first-time voter, he hopes the electricity blackouts that have plagued the country for years are the issue that will get other young people to vote. Studying audiovisual production, Mr. Vavi loses hours of work in a blackout. It also means a loss of connection to his close circle of friends, and turns his mobile phone into what he called “a very expensive brick.”

“As much as there’s been definite improvements, it’s not as good as it could be or should have been,” he said.

Hanging on the walls of the Vavi home is a portrait of the family posed with former President Nelson Mandela. Mr. Vavi’s father was once the leader of the country’s most powerful union, the Congress of South African Trade Unions, an ally of the A.N.C., and knew Mr. Mandela personally. All the younger Mr. Vavi remembers of that moment is “the hullabaloo of trying to find the bow tie” that he is wearing in the photograph.Still, Mr. Vavi said that he would not be voting for the A.N.C. He said that he had read all the parties’ manifestoes, but the politician who stood out for him did so by making a joke on X, formerly Twitter. To Mr. Vavi, the quip transformed that politician, Mmusi Maimane of the recently launched Build One South Africa party, into a relatable guy. Mr. Vavi is savvy enough to know that Mr. Maimane’s and other opposition parties won’t unseat the A.N.C., but they could shake up the party of his parents.

“The hope is that because of how unlikely it is that the A.N.C. are going to be voted out, at least scare them into picking up their socks and doing better,” he said.

‘South Africa can come back’

Dylan Stoltz, 20When Dylan Stoltz shared his dreams for South Africa with other young white South Africans, they laughed at him.

“They say you can’t do anything in this land anymore,” he said.

Mr. Stoltz’s optimism seems at odds with his surroundings in Carletonville, a dying mining town 46 miles southwest of Johannesburg. After the end of apartheid and the collapse of mining, fortunes have changed for men like Mr. Stoltz.

His grandfather had a farm of 215 acres and a senior job in a gold mine. Mr. Stoltz works as a fuel attendant in an agricultural supply store, where he serves an increasingly diverse group of farmers.

His stepfather arranged a higher-paying job for him outside of Vancouver, Canada, where he plans to go next year to work in construction for a South African émigré.

“I don’t want to leave South Africa permanently,” Mr. Stoltz said.Since 2000, the number of South Africans living abroad has nearly doubled to more than 914,000, according to census data. His plan is to work as hard as he can in Canada and make as much money as he can. Then, he’ll return to Carletonville to start a business and marry his girlfriend, Lee Ann Botes.

Fresh out of high school, Ms. Botes is considering becoming an au pair. It would give her the opportunity to travel, and perhaps finally see the ocean. Still, she, too, plans to return.

“Doesn’t matter how much the violence and crime can be, this is your home,” she said.Mr. Stoltz added, “I think South Africa can come back to where it was a few years back.”

While some white South Africans may be nostalgic for the apartheid years, for Mr. Stoltz, South Africa’s heyday was during the presidency of Mr. Mandela, when he believes there was racial unity. The closest he has come to this ideal in his own lifetime, he said, was when South Africa won the Rugby World Cup last year.

Mr. Stoltz said that he would vote for Siya Kolisi, the current captain of the national rugby team and the first Black player to lead it — if only he were running.

So he’s considering voting for the largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, or the Freedom Front Plus, once a minority Afrikaner party that has grown to become the fourth- largest in South Africa. His grandfather is a local councilor with the Freedom Front Plus.

‘I’m still waiting for someone to impress me’

Matema Mathiba, 30As a sales representative for a global brewery company, Matema Mathiba spends her days driving around South Africa’s northernmost Limpopo Province.

Ms. Mathiba spent much of her childhood in the provincial capital, Polokwane, once an agricultural center that has seen a mushrooming of large homes built by a new cohort of Black professionals. With the end of apartheid, the Mathiba family’s fortunes grew to provide a house with a bedroom for each of the three sisters, who all have college degrees.

In the struggling economy under President Cyril Ramaphosa, Polokwane is less expensive than living in Johannesburg, Ms. Maiba said, sipping a lemonade in a recently opened chain restaurant. The city is also an A.N.C. stronghold, with the party. taking 75 percent of the votes in the last election.

In the past, Ms. Mathiba had voted for the A.N.C. because, she said, “the devil you know is better.”

This election, though, she remains undecided. She is losing patience with the A.N.C., comparing the party to a 30-year-old, like herself, who should by now have a clear direction.

“A 30-year-old is an adult,” she said.

Ms. Mathiba’s church congregation of young Black professionals is her community, she says, and seeing television news footage of the A.N.C.’s tactic of campaigning in churches left a bitter taste.

“We can see through it, but can the older people?” she asked.With a degree in development planning, Ms. Mathiba actively participates in South Africa’s hard-won democracy, reading bills and commenting online. She understands the stakes of policy-making, but as part of the social media generation, she wants to know her leaders more personally.

That she knows nothing about Mr. Ramaphosa’s family unsettles her. She took notice when Julius Malema, the firebrand leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters, an opposition party, posted something personal about his children online. But she does not agree with his policy on open borders, she said.

Data show that a quarter of South African voters will make their decisions just days before the vote. So will Ms. Mathiba.

“I’m still waiting for someone to impress me,” she said.

‘When it’s time to do the action, they can’t’

Shanel Pillay, 24

As a girl, Shanel Pillay loved to go to the library. It’s where she studied, hung out with friends and met the boy who would become her fiancé.Today, Ms. Pillay says she would not risk the 10-minute walk to the library. Like many Indian South Africans living in Phoenix, a majority-Indian community founded by Gandhi when he lived in South Africa, Ms. Pillay feels that Phoenix has become unsafe. So has the surrounding city of Durban, on South Africa’s east coast. Crime keeps her indoors, producing TikTok videos to pass the time.

Ms. Pillay vividly remembers hiding in her home for several days in 2021, when Durban was gripped by deadly riots that pitted Black and Indian South Africans against each other. The violence highlighted how poor and working-class South Africans felt left behind by progress made since the end of apartheid.

Recently, parts of Phoenix have not had running water for weeks, she said.

Under apartheid policy, Indian South Africans received more economic benefits than other groups of color. Since the end of apartheid, Indians, who make up 2.7 percent of the population, have seized opportunities in education and skilled work.

Ms. Pillay wanted to become a teacher, but when she arrived at college, she picked what she hoped would be a more lucrative career: finance.

“I wanted to be successful,” she said. “Have my own house, have my own car, have a pool, although I can’t swim.”

After her stepfather fell ill and lost his income during the coronavirus pandemic, Ms. Pillay dropped out of college. Home for two years, she took a short course in teaching, and soon found a job at a small private school. On the side, she works as a freelance makeup artist.

“As an individual in South Africa, you need to be independent,” she said.She sees no point in voting. Neither large parties nor the independent candidates vying for Phoenix’s vote have wooed her.

“When it’s time to do the action,” she said, “they can’t.”

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/28/world/africa/south-africa-election-youth-vote.htmlNice to see the indigenous people of the place now called New York, former NEw Amsterdam be given some respect absent violence demanding it

‘Old’ Amsterdam Looks Back at New Amsterdam Through Indigenous Eyes

The violent history of the Dutch colony that is now New York is not well known in the Netherlands. The curators of a new exhibition want to change that.

Chief Urie Ridgeway and other representatives of the Lenape people spiritually cleansed the galleries of the Amsterdam Museum before the opening of “Manahahtáanung or New Amsterdam? The Indigenous story behind New York.”Credit...Françoise Bolechowski/Amsterdam Museum

By Nina Siegal

Reporting from AmsterdamMay 24, 2024

In the language of the Lenape Indigenous people, the word for European explorers who crossed the Atlantic in the 17th century to settle on their lands was “shuwankook,” or “salty people.”The term first applied to the Dutch, said Brent Stonefish, a Native American spiritual leader, because they emerged from the sea to first trade with, then exploit and kill, his Lenape ancestors.

“The Dutch were basically those who ran us out of our homeland, and they were very violent toward our people,” he said in an interview. “As far as I was concerned, they were the savages.”

So, when the Dutch Consulate in New York approached Stonefish to ask if he’d help commemorate the anniversary of the 1624 establishment of the first Dutch settler colony, New Amsterdam, he was taken aback.

“They wanted us to celebrate 400 years of New Amsterdam, and we’re like, ‘No, that’s not going to happen,’” he said. “At the same time, I thought it was an educational opportunity,” he added. “We had a lot of hard discussions.”

The Dutch Consulate, which was creating an events program around the anniversary called Future 400, then connected Stonefish with the Museum of the City of New York and the Amsterdam Museum, an historical museum in the Netherlands.The result is the exhibition, “Manahahtáanung or New Amsterdam? The Indigenous Story Behind New York,” running at the Amsterdam Museum through Nov. 10 and moving to the Museum of the City of New York in 2025 as “Unceded: 400 Years of Lenape Survivance.”

Imara Limon, a curator from the Amsterdam Museum, said that the project was a true creative collaboration between the museums and the Lenape, including the organization that Stonefish co-directs, the Eenda-Lunaapeewahkiing Collective. It felt particularly important, Limon said, to present the show in the Netherlands, where few people are aware of the Dutch colony’s impact on Indigenous peoples.

“It wasn’t part of history classes in school,” she said. “And we realized that our institutional memory on this topic is also very limited, so we needed their stories.”

Each museum searched its holdings for material about the Lenape, but found only a few official records. In the Amsterdam City Archives, curators discovered a record of an enslaved Lenape man who was brought to the Netherlands in the 17th century, which is on display in the show. To supplement the documents, the Lenape contributed artworks and traditional ceremonial artifacts.Objects are just one part of the show, however: The exhibition is dominated by video interviews with Lenape people, which run from about seven minutes to 50 minutes each.

“Usually in a museum exhibit, videos are three to five minutes long,” Limon said, “but here we made them longer, because we felt we wanted to have them really present, physically present, in the space.”Cory Ridgeway, a member of a Lenape group that collaborated on the show, said she welcomed this approach.

“Traditionally museums want very object-based programming, and they will come to us and say, ‘Give us some stuff and we’ll talk about it,’” she said. “A lot of museums don’t really credit oral history as history, and that’s our main form of history.”

Stonefish said his primary goal was to show that the Lenape still exist, and that they still have a voice.“The one thing we wanted to convey was that we weren’t a relic under glass,” he said. “We still live and breathe, and strive to live good lives.”

Some 20,000 living Lenape people are descendants of an estimated population of one million that originally lived in the region of present-day New York, Connecticut, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

In 1609, the Dutch East India Company, one of the world’s largest merchant firms, dispatched the English explorer Henry Hudson to find a trading route to China. But Hudson veered off course and arrived in the Bay of Manhattan.

He quickly claimed the whole area between the Delaware and Connecticut rivers for the Netherlands. There, Dutch merchants engaged the Lenape in trade for beaver pelts and other furs.

Later, the Dutch West India Company, founded in 1621, established its first settlement on Governors Island in 1624, and made its colony of New Amsterdam on the tip of Manahahtáanung, what is now Manhattan. Two years later, a company executive, Peter Schagen, said he had purchased Manhattan from the Lenape for 60 guilders, or approximately $24.

The Lenape dispute that claim.“We say that that’s a myth,” Stonefish said. “We didn’t have a concept of ownership; we had a concept of sharing the land, and having a relationship with all of the land, the animals and the plants. Our idea of civilization was accepting all of creation, and taking no more than what we needed.”

In the exhibition, this myth-busting is represented by a wampum belt, specially created for the show. Stonefish said a ceremonial belt would have been given to the Dutch as part of any property-sharing agreement, but there was no mention of one in the Dutch account. “Our leadership would not have entered into any type of agreement without something like this,” he said.

For about two decades, trade continued between the Dutch and the Indigenous people, but in 1643, the New Netherlands governor Willem Kieft ordered the massacre of the Lenape and other tribes living in the colony.

A two-year war ensued, during which at least 1,000 Lenape were killed. Kieft was ordered to return to the Netherlands to answer for his actions, but died in a shipwreck.

The West India Company appointed Peter Stuyvesant as Kieft’s successor, and he managed New Netherland until the English conquered the territory in 1664, and renamed it New York. The Dutch colony lasted just 50 years.Ridgeway, the member of the Lenape group, said that, for her, making connection with the “salty people” was an opportunity to initiate discussions with the Dutch government about healing the past’s wounds.

“I would love to see an apology, and I would like to see reparations,” she said. “It would be used for our language, which is nearly extinct, so that it can be spoken again, and for our elders. The majority of our people are living below the poverty level today.”

Her husband, Chief Urie Ridgeway, said the story of his people had been largely erased from American history books, but it has been transmitted through storytelling by generations of survivors. “We know our histories, but now we are starting to share them.”

He added that the current exhibition gives the Lenape a chance to tell a story that has long been ignored. “It’s about time,” he said.

URL

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/24/arts/design/amsterdam-museum-indigenous-new-york.html

A correction was made on May 24, 2024: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the organization that Brent Stonefish co-leads. It is the Eenda-Lunaapeewahkiing Collective, not the Delaware Nation Collective.

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)