-

Posts

3,760 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

118

richardmurray's Achievements

Single Status Update

See all updates by richardmurray

-

MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke starting a Haka!!

Kawana ka whakamanuwhiritia koe e au!!!

“Oh Governor, Government, you are only visitors here” !!

https://www.tumblr.com/0ne0nlylarry/767494474959044608/have-watched-clips-of-mp-hana-rawhiti-maipi-clarke?source=shareHer actions were about a law concerning the Treaty of Waitangi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Waitangi

Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill

https://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/government/2024/0094/latest/LMS1003433.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_Treaty+Principles+Bill_resel_25_a&p=1New Zealand’s Youngest MP-Elect in 170 Years Is Māori and Proud—but Also Concerned

By Chad de GuzmanNovember 9, 2023 5:30 AM EST

Last month’s elections in New Zealand heralded significant change, promising to bring to power the country’s most conservative government in decades. [ https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/14/world/asia/new-zealand-election-national-wins.html ]But alongside the rightward shift from six years of Labor Party leadership to an expected National Party-led coalition, the incoming parliament will also feature the most-ever Māori members, [ https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/301002369/whos-representing-you-record-for-mori-mps-but-fewer-women-in-parliament ] most of whom are in the opposition.It’s a striking contrast that 21-year-old Māori MP-elect Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, set to be New Zealand’s youngest lawmaker in 170 years, is well aware of.

As race issues took center stage across the nation during election season, [ https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/race-issues-emerge-new-zealands-election-2023-10-03/ ] Maipi-Clarke’s family home [ https://www.1news.co.nz/2023/09/30/racial-slurs-shouted-during-invasion-of-te-pati-maori-candidates-home/ ] was vandalized by a man who shouted slurs. Among the National Party’s priority plans [ https://assets.nationbuilder.com/nationalparty/pages/18431/attachments/original/1696107664/100_Day_Action_Plan.pdf?1696107664#page=2 ] is to ax the Māori Health Authority, which is tasked to bridge the gap between the health quality of indigenous and non-indigenous people. And the right-wing ACT Party, which is expected to partner with the National Party, had earlier proposed a referendum [ taken down ; https://www.act.org.nz/act_proposes_referendum_on_co_governance ] that would reconsider the role of the Māori people, who make up about 17% [ https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2022/ ] of the national population, in policymaking.

Maipi-Clarke, who will represent the indigenous-advocating Māori Party when the new parliament opens later this year, says Māori have withstood tides of oppression before, and she, like her people, won’t buckle under renewed pressure. “When it was hanging on a string just on the last thread, we still survived seven generations with the suppression towards our people,” she says. “We will always look after ourselves and everything surrounding us, so we will always look after others as well.”

Much about Maipi-Clarke screams Gen-Z, albeit perhaps over-accomplished for her age: she runs a community garden, she’s active on Instagram and TikTok, and she authored a book on using the Māori calendar for physical and mental healing. [article is below] She lacks legislative experience, but politics runs in the family: her great-great-great-great-grandfather Wiremu Katene was the first Māori minister to the Crown in 1872; and her aunt, Hana Te Hemara, was responsible for delivering the Māori language petition to parliament in 1972 that paved the way for its widespread adoption in New Zealand.

When Maipi-Clarke decided to stand for election, many probably didn’t think she stood a chance. Her Hauraki-Waikato electorate was already represented by Māori political veteran (New Zealand’s Mother of Parliament) Nanaia Mahuta, who was also the country’s first female Māori foreign minister in the most recent Labor Party cabinet.

“I guess for me the competition wasn’t my opponent,” Maipi-Clarke tells TIME from her home in Huntly—a quaint town some 53 miles southeast of Auckland. “I think she’s amazing at politics and she’s been so inspiring for me to go through politics. But my competition was the people who weren’t engaged in politics.”

Maipi-Clarke spoke briefly with TIME about her campaign and election as well as her hopes and fears heading into what looks to be a tumultuous parliament.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Do you think that the Māori community has become more active politically in recent years?

Personally, Māori people have always been political, but political in their shape and form—not so much in the Westminster government that we have in New Zealand. So it’s kind of translating to that to our people, how this affects us. And ever since Te Pāti Māori [the Māori Party] has had a comeback since 2020, and was able to get our two co-leaders in Rawiri Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer into parliament, there’s just been this whole new wave, and people who never thought would be into politics are now into politics because of our party.

Has there been enough voter movement from the youth demographic and do you think that enabled you to secure a seat in parliament?

I think for a long time we kept hearing, “Oh, young people don’t vote. You guys are lazy.” But really, all different types of different people were saying this. And I thought to myself, why would we vote? These people in politics are not telling our stories. They’re not representing us. So I didn’t blame younger people for not voting. And we still have a lot more to do but I think this is a great start for people to be engaged in translating that language of politics and how it affects them.

You’ve said you view yourself as a kaitiaki (guardian) of the Māori language and tradition. In what ways do you plan to guard Māori language and tradition?

I think when I look at a politician, there’s been so many things already that I’m trying to challenge the status quo—from the title that you give to the thing that you hold, from what I wear to the kind of language I’m talking, it’s always being in touch with my people and in touch with the people that I represent. Because far too often, I see politicians talking and they’re completely out of touch with our reality that we face.

So I think, for me, being a guardian is: one, hearing what our people are going through, because I may not know all the stories; two, advocating and talking on that openly within parliament and in the chambers and in policy transformation; and three , actually finding different ways of engaging.

Are there any specific priorities or legislative agenda that you want to pursue as an MP?

Usually an MP in Aotearoa [New Zealand] will focus on one thing but for us in Te Pāti Māori, being the only indigenous political party in Aotearoa, we have to cover everything. I’m looking at our Te Tiriti o Waitangi [Treaty of Waitangi] because other parties said that they want to have a referendum on that.

Looking at the two main priorities for me coming into this was our indigenous ways of looking after our environment and looking after younger people who would usually go into gangs or who don’t feel connected to the culture. So those are probably my two top priorities, but like I said, there’s so much to cover.

How does mātauranga (Māori knowledge) shape your framing of the legislative agenda you want to pursue, in regards to the climate crisis, and inclusivity?

For me, I feel like there’s not enough representation of the LGBTQ community, the takatāpui whānau, within politics. There’s not enough representation of Pacific peoples as well. So there’s a lot of those minority groups that aren’t represented in politics, but also the lack of attention from a lot of other parties towards these communities and secondly towards climate change. So I guess there’s so much mātauranga and knowledge out there on how we can be inclusive and how we can really solve the climate crisis, how we can engage indigenous ideas in systems.

So mātauranga—knowledge from not just Māori but indigenous people specifically within the Pacific and our great migration to Aotearoa—allowed us to be scientists in our own ways, it allowed us to calculate our environment, allowed inclusion. It was a whole other perspective that colonialism actually wiped out through the Tohunga Suppression Act. I think this generation from our elders have reinstalled that mātauranga, and now within these spaces, now we can talk about it and how our systems can be solutions.

How do you feel Māori-specific legislation may fare under the leadership of the National Party?

It's going to be very interesting, and I think we’re in for a hell of a ride. Because they’re looking at taking us back 180 years with subjects like putting a referendum on the treaty from the coalition partners, ACT, who have a really racist rhetoric coming out of the party. So it is quite fearful for our people. But even if it was a Labor Party government or National Party government, Māori have been in opposition for 180 years, so we can hold our line strong. But this political election was so nasty, so racist, especially to our whānau [family] and the LGBTQ community. So, looking at the most vulnerable and minority demographics. It’s been quite challenging for people to digest. So even if they don’t create legislative change, what’s coming out of their mouths is very detrimental to a lot of people in Aotearoa.

Do you think the region has been struggling with recognition and equitable rights for its indigenous and first people citizens? Australia recently failed to approve an amendment recognizing the rights of indigenous citizens in its constitution. Are you concerned about a rising trend in Oceania against indigenous people?

Absolutely, definitely concerned, definitely fearful of our rights as indigenous people, like our Aboriginal whānau. That was, and always will be, indigenous land over there. I’m concerned for us here in Aotearoa, with the potential referendum on our treaty; concerned for whānau on the island of Tuvalu that’s going to be underwater; concerned about different indigenous cultures all the way to Palestine. I mean all indigenous cultures are at a great risk, and I think the only hope that we have is our elders teaching us and the next generation being unapologetic around how we still stand up and hold that front line.

It’s up to all humans whether they care or not. I think if you care about Māori culture, you have a great appreciation for the way that we look after: we look after our land, we look after our people, we look after our culture and our language. We will always look after ourselves and everything surrounding us, so we will always look after others as well.

https://time.com/6333369/hana-rawhiti-maipi-clarke-new-zealand-maori-young/

Empowering whānau through māra kai and the maramataka

Contributing writer ; Te Kuru o te Marama Dewes

Meet the young Waikato woman who is using the maramataka and Matariki to help whānau grow kai on their whenua.

Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke (Waikato, Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Porou, Te Atiawa, Ngāi Tahu) from Waahi Pā in Rāhui Pōkeka is helping her people connect to the taiao through māra kai (food gardens) and mātauranga Māori tied to the maramataka.

Working with the Ministry of Primary Industries as a facilitator for whānau Māori who own land, she’s helping them to put kai on to their whenua.

“I help them get the expertise of MPI in the way of feasibility studies, horticulturalists, any experience stuff,” says Maipi-Clarke.

There are three areas in Waikato territory that are currently being developed, while the main māra kai at Kāhui Tua in Rāhui Pōkeka has been in the works for the last three years.

“We introduce whānau to the maramataka and time if they don’t know of it. From there, we do workshops and then introduce resources,” says Maipi-Clarke.

The māra kai are informed by the maramataka.

“In Whiro we rest, in Ohoata we’re planning, in Okoro we’re doing seedlings, in Tamatea we’re harvesting, in Rākaunui and Tamatea-ā-mua we’re having community planting days,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Finding a balance between mātauranga Māori and western science, she leans on her elders for their knowledge of unforeseen phenomena and how to respond in a Māori way before bringing in a horticulturalist to gather their insights and share those with whānau.

“It’s about doing what’s best for the māra,” says Maipi-Clarke.

A background in maramataka

For Maipi-Clarke, learning about maramataka is encompassed by a holistic understanding of the wider taiao.

“I’m not a holder of knowledge but I’m a messenger for my generation to navigate mental health with knowledge from our taiao,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Growing up she was influenced by her aunty Liliana Clarke, who is currently doing a PhD around maramataka, while learning through the behaviour of her cousin, Clarke’s son, who has Asperger’s.

“He really went with the maramataka. We could prepare as a whānau when he’d have times when he’d need more help. It was just natural,” says Maipi-Clarke.

However, what really sparked her interest was a collective wānanga on taiao with Rereata Makiha, Hoturoa Kerr, Rikki Solomon and Dr Rangi Mātāmua.

From there, she spent every summer with her aunty, learning through the process of archiving her research, while being exposed to the teachings of knowledge holders such as Pine Taiapa and Rereata Makiha.

In 2020, Maipi-Clarke launched her own resource called Maahina, which seeks to help rangatahi better understand their taiao.

“Maramataka isn’t tapu. It should be spoken about. It should be wānanga’d about. It’s how our tūpuna would navigate when and where to plant kai. Kūmara is ‘noa’.”

She wants tamariki and rangatahi to be more in tune with themselves, to develop the ability to observe their own patterns with maramataka.

“The whole goal is that tamariki in the morning and look at the marama, the whetū from the night before, the sun, the clouds and every little thing, to pick up how their day is going to be or the aspects of their day. What to watch out for or be aware of.”

A passionate advocate for rangatahi mental health and education through maramataka, the 19-year-old paints an indigenous perspective that reflects maturity and leadership beyond her years.

“Maramataka, the stars, the tides of the sea, they’re all notifications in the sky and our taiao. Rather than looking down at our phone, we can look up for free and see our own affirmations,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Working with tangata whenua

For the Kāhui Tua māra, the whānau expressed aspirations for a food forest. Utilising their land, they dedicated sections to the various stars of Matariki.

“In Tipu-ā-nuku and Tipu-ā-rangi, those sections have rīwai, kamokamo, kāroti, lettuce, everything from the ground. In Tipu-ā-rangi they’ve got berries, orchards, miro, all the food from above. In Matariki and Rēhua they have their rongoā space, that’s food foraging, kawakawa, kūmarahou and all that,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Looking ahead, one of their goals is to have a space for Waitī by using one of their traditional pātaka kai, lake Waahi, for watercress, kōura and tuna.

“Those are the frameworks that we use for planning, then we incorporate the maramataka and bring a horticulturalist. We don’t provide the tools, shovels, or seedlings, stuff like that, it’s just mātauranga support,” says Maipi-Clarke.

In her role with MPI, Maipi-Clarke has been able to mobilise her community and support them to realise these aspirations for the whenua.

“The next project near Matamata is with Ngāti Hinerangi and Wairere Toi, who already have a work crew and resources, they just need a bit of help with incorporating maramataka and knowledge around growing kai,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Connecting whānau to whakapapa and whenua

The planning, planting and harvesting are all very intentional, reflecting how their ancestors utilised the rich lands throughout Waikato to grow an abundance of produce.

“We’ll usually get a feel for the whakapapa of the whenua. Our tupuna wahine, Whaawhaakia, her descendants are Ngāti Whaawhaakia and she was known for her kūmara,” says Maipi-Clarke.

At Te Whare Taonga o Waikato, there is a carving depicting Whaawhaakia holding a kō, a digging stick used to cultivate soil, with a kūmara basket at her feet.

“So we’re working with the whānau to emphasise their kūmara and we had a planting day of just wāhine who came in to harvest kūmara, linking Whaawhaakia to her descendants,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Māra kai in outdoor education

Ensuring those connections are made early, they invited kids from the local kōhanga reo to plant rōpere and four months later they came back to harvest them.

“We taught them why we were planting at that particular phase, which was Tangaroa-ā-mua. We explained what stars were setting and how the different atua would feed the māra,” says Maipi-Clarke.

Te Wharekura o Rākaumangamanga helps out with working bees when extra hands are needed for a harvest, again reinforcing the ties throughout the community across generations.

Māra kai crates to give back

One of the ideas behind the māra was to enable whānau to pull up their own kai crates for Christmas, so they wouldn’t have to worry about getting kai. However, when the pandemic came along, they had to cancel those harvests for the safety of their people and reduce chance of transmission.

Waahi Pā, a local marae in Rāhui Pōkeka which is also a key stakeholder in this project, acted as a distribution point for the kai parcels for kaumātua and whānau during the pandemic, as well as an MIQ.

“We sussed out Tipu-ā-nuku and Tipu-ā-rangi, with lemons, all the leafy greens, kūmara, potatoes, kamokamo, strawberries, watermelon, dropping them off the kaumātua of Waahi Pā,” says Maipi-Clarke.

This was supplemented by another local whānau who delivered kina, muscles and other kai to acknowledge Waitī and Waitā.

Matariki and the hautapu

One of the sections in the Kāhui Tua māra was dedicated to Matariki, where the whānau put their best seeds in to plant and harvest kai for Tipu-ā-nuku, Tipu-ā-rangi, Waitī and Waitā, to have in their hautapu ceremony.

“This kai wasn’t to be consumed by humans but for atua,” says Maipi-Clarke.

This included kūmara hutihuti, which is a white kūmara that Waikato ancestor Whakaotirangi brought from Hawaiki, reinforcing again that connection to whakapapa and whenua.

Every year, Maipi-Clarke and her whānau aim to upskill themselves to be self-reliant for the hautapu ritual.

Looking back, she says they’ve come a long way from roasted marshmallows on the marae ātea in 2017.

“The next year, we had to bring a waiata and explain how that waiata represented a person who had passed away,” says Maipi-Clarke.

The benefits of the revitalisation of the tikanga are providing an opportunity for those who are dealing with grief to shed some of that weight through the hautapu ritual.

“Our whānau have gone through a lot of suicide deaths, my mates from kura. So it’s getting in contact with our whānau pani and telling them to come to hautapu and let go of that mental baggage,” says Maipi-Clarke.

“I think everyone is keen to acknowledge and celebrate it, sometimes whānau might get shy because they don’t know how to do a long karakia, so it’s catering to them with different options of how you can celebrate Matariki and different activities.”

They learnt different variations of Matariki throughout Waikato before starting their own hautapu ceremony, now by harvesting their own kai they’re an exemplary model for others to follow.

“We could have gone to the supermarket and bought them but we wanted that aspect of growing them specifically for our atua,” says Maipi-Clarke.

With the focus on planting and harvesting being driven by the purpose of cultural ritual and connection to whakapapa, Maipi-Clarke has high hopes for a circular Māori economy based on kai.

“Hopefully in years to come we’ll be exchanging kai rather than moni for kaupapa Māori,” says Maipi-Clarke.

In the long run, after looking after her own backyard, she hopes to help other iwi get māra kai established while supporting them with knowledge around the maramataka.

https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/11-07-2022/empowering-whanau-through-mara-kai-and-the-maramataka

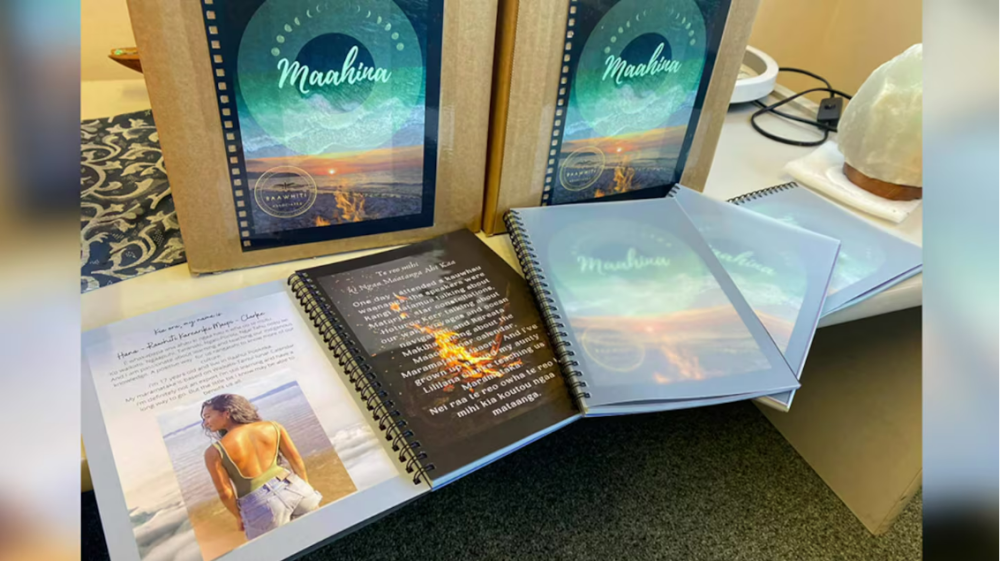

17-year-old launches book about maramataka Māori

Thursday, July 2, 2020 • ByJessica Tyson

Today Te Wharekura o Rakaumangamanga student Hana Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke launches her new book at her school in Huntly.

The book, Maahina, encourages rangatahi to take an interest in the stars and the moon to heal themselves.

“I wanted rangatahi Māori to become more aware of the environment and how it can help us physically mentally and emotionally and help us with the everyday things we do in life like studying and NCEA.”

The 17-year-old created Maahina about seven months ago.

“It was a little scary just because there are 400 different variations of maramataka within each iwi so I had to make sure I was doing it properly and then I brought the kaupapa into my school and they helped me support me and here I am today with my book.”

Part of her journey started when she attended a lecture where Māori astronomer Professor Rangi Matamua, the captain of the oceangoing waka Haunui, Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, and Māori astrologer Rereata Makiha spoke about the Matariki star constellation, ocean navigation and maramataka Māori.“I was looking around the room and there were not many rangatahi there, and I was like ‘If our generation was to know about this I feel we’d become more in tune and it would help us with our overall wellbeing and health’.”

Maipi-Clarke says the book covers three different phases about the maramataka (calendar).

“There’s a low, high and medium, just like the natural waves of life, and it’s just applying little things to those elements.”

During a low phase she focuses her time on studying and on the high phase, she asks her teacher if the due date for an assignment can be moved there.

“Eventually I want this out there for all my generation because we are the millennial generation, the ones who have all the technology these days so it would be so good if we could all learn a little something now that this is available to us.”

Maipi-Clarke says would like to continue studying the maramataka once she starts university. For now, she is looking for a way to sell her new book online.

https://www.teaonews.co.nz/2020/07/03/17-year-old-launches-book-about-maramataka-maori/

Massive crowds march on New Zealand parliament protesting Māori bill. Here’s what to know

By Helen Regan, CNN

3 minute read

Published 1:55 AM EST, Tue November 19, 2024

Tens of thousands of people have marched on the New Zealand parliament in Wellington to protest against a bill that critics say strikes at the core of the country’s founding principles and dilutes the rights of Māori people.

The Hīkoi mō te Tiriti march began nine days ago in New Zealand’s far north and crossed the length of the North Island in one of the country’s biggest protests in recent decades.

The traditional peaceful Māori walk, or hīkoi, culminated outside parliament on Tuesday, where protesters implored lawmakers to reject the controversial Treaty Principles Bill that seeks to reinterpret the 184-year-old treaty between British colonizers and hundreds of Māori tribes.

The legislation is not expected to pass as most parties have committed to voting it down, but its introduction has triggered political upheaval and reignited a debate on Indigenous rights in the country under the most right-wing government in years.

Here’s what you need to know:

What’s happening?

Massive crowds marched through the New Zealand capital as part of the hīkoi, with people waving flags and signs, alongside members of the Māori community in traditional clothing.

Police said about 42,000 people, a significant number in a country of about 5 million people, marched toward parliament to oppose the legislation.

Those attending described the march as a “generational” moment. “Today is a show of kotahitanga (unity), solidarity and being one as a people and uphold our rights as Indigenous Māori,” marcher Tukukino Royal told Reuters.

Protesters gathered outside parliament, known as the Beehive, as lawmakers discussed the controversial bill.

Last week, parliament was briefly suspended after Māori lawmakers staged a haka to disrupt voting on the bill.

What is the Treaty of Waitangi?

New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi is a document signed by the colonial British regime and 500 Māori chiefs in 1840 that enshrines principles of co-governance between Indigenous and non-Indigenous New Zealanders.

The treaty is considered one of the country’s founding documents and the interpretation of its clauses still guides legislation and policy today.

Two versions of the text – in Māori, or Te Tiriti, and English – were signed but each contains differing language that has long sparked debate over how the treaty is defined and interpreted.

Unlike the United States, New Zealand doesn’t have a written constitution. Instead, the treaty’s principles have been developed over the past 40 years by successive governments and courts.

The agreement seeks to protect Māori interests, their role in decision-making and relationship with the British Crown. And courts have used the principles to redress Māori disenfranchisement and enact policies that seek to remedy social and economic disparities Māori face.

What is the bill?

The Treaty Principles Bill was introduced by David Seymour, leader of the right-wing ACT New Zealand Party, which is a junior coalition partner with the ruling National and New Zealand First parties.

Seymour says he does not seek to change the text of the original treaty but argues its principles should be defined in law and should be applicable to all New Zealanders, not just Māori.

Supporters of the bill say the ad hoc way in which the treaty has been interpreted over the years has given Māori special treatment.

The bill, however, is widely opposed by politicians from both sides of the aisle and thousands of Indigenous and non-Indigenous New Zealanders, with critics saying it could undermine the rights of the Māori.

Seymour was met with chants of “kill the bill, kill the bill” when he briefly walked out of parliament to meet the crowds on Tuesday, according to CNN affiliate Radio New Zealand.

Hīkoi leader Eru Kapa-Kingi told the crowd “Māori nation has been born” today and that “Te Tiriti is forever,” RNZ reported.

.thumb.jpg.ed52910791d00308abb8c218695bec88.jpg)