A New Introduction to The New Negro: An Interpretation

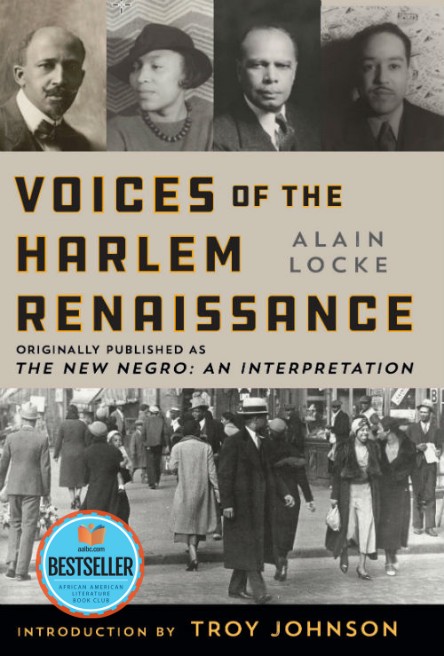

The following is a revised version of the introduction, written by Troy Johnson, for Voices of the Harlem Renaissance (Konecky & Konecky, March 1, 2020), which was originally published as The New Negro: An Interpretation

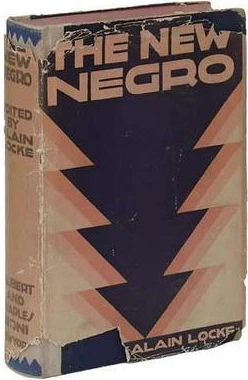

The New Negro: Voices of The Harlem Renaissance was originally published in 1925 by the Albert and Charles Boni Publishing Company. Dr. Alain LeRoy Locke edited this groundbreaking anthology, which he described as “…embodying these ripening forces as culled from the first fruits of the Negro Renaissance.”

This preeminent collection introduced the artistic and cultural expression of African American writers, poets, and artists to a wider audience. Almost 100 years later, this treasure trove of innovative work by our foremost thinkers, creatives, and storytellers, continues to inspire and inform a new generation of writers, thought leaders, intellectuals, and activists inciting change today, on a global scale.

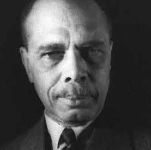

Locke was born in Philadelphia, PA on September 13, 1885. A highly accomplished academic and intellectual, he was the first African American Rhodes Scholar and earned a PhD in philosophy at Harvard University. Jeffrey C. Stewart, the author of Locke’s Pulitzer Prize winning biography, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke published by Oxford University Press in 2018, describes Locke;

“Alain Locke a tiny, fastidiously dressed man emerged from Black Philadelphia around the turn of the century to mentor a generation of young artists including Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Jacob Lawrence and call them the New Negro — the creative African Americans whose art, literature, music, and drama would inspire Black people to greatness.”

Despite his small stature Locke loomed large in terms of accomplishments. An educator, philosopher, and patron of the arts he is recognized as the “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance,” not only for his literary contributions, but for his behind the scenes work supporting authors, and teaching at Howard University, a historically Black college in Washington, DC, for over 40 years.

The Harlem Renaissance marked a period, encompassing the entire 1920s, when African American artistic expression and outreach grew dramatically. The Harlem Renaissance was also a time when published African American work was more political and bolder than any previous era since the abolitionist movement of the mid-19th century, when African American anti-slavery activists like Frederick Douglass published the first of three biographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (1845) and the anti-slavery newspaper The North Star (1847 to 1851). Other groundbreaking biographies published during that time included Twelve Years a Slave (1853) by Solomon Northup, and Ellen Craft’s Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (1860).

The New Negro is not only a time capsule of African American life from a century ago, it is the foundation to help us understand not just African American culture, but American culture, because the African American experience is central to the American experience. It shapes it financially, culturally, emotionally, societally, and morally and has for the last 400 years. This book is widely recognized as the most significant publication from the Harlem Renaissance and it continues to showcase our accomplishments, creativity, and talents and inspire African Americans to greatness.

The New Negro is not only a time capsule of African American life from a century ago, it is the foundation to help us understand not just African American culture, but American culture, because the African American experience is central to the American experience. It shapes it financially, culturally, emotionally, societally, and morally and has for the last 400 years. This book is widely recognized as the most significant publication from the Harlem Renaissance and it continues to showcase our accomplishments, creativity, and talents and inspire African Americans to greatness.

The Akan people of West Africa brought us the concept of Sankofa; “It is not taboo to fetch what you have forgotten.” The lesson is that we must reach back and gather the best of what our past teaches us, so that we can achieve our full potential as we move forward. Many others have said you can’t understand your present, or future, unless you understand your past. The New Negro provided a basis for understanding the past, present, and future of America.

When we look back at the genesis of The Harlem Renaissance, we see it could not have happened without The Great Migration, the largest internal migration of people within the United States. In the 60-year period between 1910 and 1970, over 6 million African Americans moved out of the rural South and migrated to cities in the West, Midwest, and Northeast. A few of the most popular destinations included Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, and New York. All these cities benefited from the arrivals who had an immediate influence on cuisine, music, art, and literature. These cities could all boast of vibrant African American communities, but the village of Harlem, located in the northern portion of New York City’s borough of Manhattan, was viewed during the 1920s as the mecca of Black culture, nationally and internationally.

The Harlem Renaissance was also a period of African American affirmation and self-expression. Its principal contributors were not bounded by the geography of Harlem. They were not limited by gender, age, sexuality, or even race. African Americans were not a monolith in the 1920s, any more than they are today. This diversity, and diversity of expression is shown to great effect in the New Negro, through the work of writers, artists, poets, musicians, dramatists, scholars, and philosophers from around the country, and the world, and from all walks of life.

The figures of the Harlem Renaissance were also a part of the great migration landing primarily in Northern and Midwestern cities. The most notable were not based in Harlem, or even New York City. Locke only moved to New York City in 1953, after he retired from Howard University, and shortly before his death on June 9, 1954. Charles S. Johnson, who would become the first black president of Fisk University, a historically Black university located in Nashville Tennessee, was born in and spent most of his life in the south. Many of the other contributors were born abroad; Eric D. Walrond, British Guiana; Claude McKay and W.A. Domingo, Jamaica; and Arturo Schomburg, Puerto Rico (born in 1874, before Puerto Ricans became U.S. citizens in 1917). Only two of the contributors were born in New York.

The women are no less impressive. Zora Neale Hurston’s, award winning, short story “spunk” is included. “The Task of Negro Womanhood,” by Elise Johnson McDougald offers a sobering overview of the social condition of African American women. McDougald concludes with, “the wind of the race’s destiny stirs more briskly because of her striving.” The aspirational theme of striving resonates throughout the book, though the sentiment may not be expressed with unbridled optimism as depicted at the end of Angelia Grimke’s poem, “The Black Finger;”Why, beautiful still finger, are you black?

And why are you pointing upwards?

Locke ensured the work of writers, spanned multiple generations. When the book was published, in 1925, the ages of writers ranged from age 20 (Richard Bruce Nugent, born 1905) to 58 (Russa Robert Moton, born 1867). The balance between young and more seasoned writers is important. In 1926, 24-year-old Hughes, 21-year old Nugent, and others launched the African American literary magazine Fire!!, which gave younger writers more exposure. The magazine lasted only one issue but is still recognized as a substantial contribution of the Harlem Renaissance and to African American cultural expression.

Themes of sexuality are not explicitly addressed in the anthology, however, Richard Bruce Nugent was openly gay when the book was published, during a time in American history when most gay men kept their sexuality hidden from the public. Other gay contributors include Langston Hughes and Locke himself.

Jean Toomer, famously, resented being referred to as a Negro, despite his African American ancestry. Toomer is the author of the brilliant book of poetic prose, Cane (1923), the only book he published. The anthology has two excerpts from Cane and two of Toomer’s poems — a fine introduction to a brilliant though not prolific writer.

The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance, was born from a special issue of Survey Graphic Magazine, “Harlem Mecca of the New Negro.” This issue was published in March of 1925 and was guest edited by Locke. Much of the material that appears in the magazine also appears in this book. The March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic has been kept in print by Black Classic Press of Baltimore, MD.

The voices of the Harlem Renaissance have reverberated throughout the American literary landscape for almost a century. No aspect of our cultural expression since then is free of their influence. Indeed, no other period in which we witnessed a surge in both, the awareness, and output of African American creativity captures more reverence than the Harlem Renaissance.

The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970 rests on the shoulders of the Harlem Renaissance, but was less dependent upon the patronage, or validation of whites. Carla Kaplan, Professor of American Literature, Northeastern University describes this in an interview with, 15minutehistory.org;

The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970 rests on the shoulders of the Harlem Renaissance, but was less dependent upon the patronage, or validation of whites. Carla Kaplan, Professor of American Literature, Northeastern University describes this in an interview with, 15minutehistory.org;

“Charlotte Osgood Mason was the principle female white patroness, or philanthropist, of the Harlem Renaissance. She gave enormous amounts of money to black writers. Without her we might not know Langston Hughes and his poetry, and we might not know Zora Neale Hurston and her anthropology and her novels.”

Kaplan goes on to say;

“She locked into this idea that blacks were more alive and more essential, but that they were also more intellectually backward, and they should help revitalize whites. So, she’s an interesting case of someone who does a lot of good, but she does it for her own reasons and from a place we would today describe as racist. In her day she was very much appreciated for the good she did, but she was also very difficult for the blacks with whom she worked.”

Zora Neale Hurston’s book, Barracoon, which is based on a series of interviews with Cudjo “Kazoola” Lewis (1840 – 1935), the last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade. Kazoola survived capture in Benin, the middle passage, enslavement in America, and lived to tell about it. Hurston’s trips to Alabama and the project to create the book of Kazoola’s life were funded by Mason. However, the book was not published until 2018 by Amistad Press. Conflict between Hurston and Mason delayed publication of the book for several decades. Barracoon was published to critical acclaim and won many awards. Despite her prodigious talent Huston would ultimately move back to Florida, find work as a maid, and die in obscurity in 1960.

Female white patrons like Mason were collectively called “Miss Anne,” white women, who may have been well meaning, but were sometimes condescending or racist in their attitude toward African American people. Carl Van Vechten a white male patron, who was also a writer and painter, had a similarly controversial relationship with African American artists. In 1926 Van Vechten published the controversially titled novel, Nigger Heaven. The title, even in 1926, revealed a lack of sympathy or empathy for the people whose culture he purportedly admired.

When The New Negro was published, in 1925, the term “Negro” was used to describe Americans of African descent. Today, almost a century later, the word is antiquated and considered by some to be offensive. However, in 2020, there are many African Americans who were alive when the word “Negro” was widely used. To this day, some of these people prefer the term “Negro” over “Black” or “African American.” Others feel “Negro,” like “Colored,” are terms that were given to us and used by racists during Jim Crow era. The term “Negro” will be dropped from the 2020 census. “African American” is not a perfect term, perhaps there isn’t one which can universally please or even accurately represent, every member in the group it is attempting to describe.

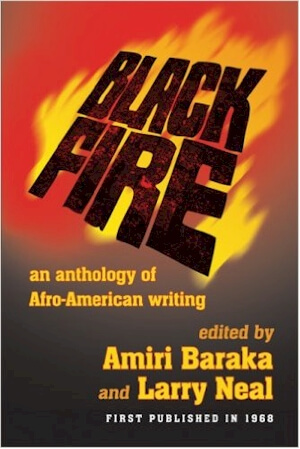

The use of “Black” by African Americans to describe themselves gained popularity in the 1960s, during another period of heightened creativity known as the Black Arts Movement (BAM). “Black” is not a new term; it was used on the 1850 United States Census. Nor was it coined by African Americans to describe themselves. It is a term that has been taken over and rebranded by African Americans. It has been turned into a term of strength and unity, as in “Black Power!” BAM’s artistic expression was intimately tied to political expression, institution building, self-determination, and independence.

The use of “Black” by African Americans to describe themselves gained popularity in the 1960s, during another period of heightened creativity known as the Black Arts Movement (BAM). “Black” is not a new term; it was used on the 1850 United States Census. Nor was it coined by African Americans to describe themselves. It is a term that has been taken over and rebranded by African Americans. It has been turned into a term of strength and unity, as in “Black Power!” BAM’s artistic expression was intimately tied to political expression, institution building, self-determination, and independence.

Etheridge Knight (1931-1991) a poet of the Black Arts Movement elaborates on the fierce independence epitomized by BAM;

“Now any Black man who masters the technique of his particular art form, who adheres to the white aesthetic, and who directs his work toward a white audience is, in one sense, protesting. And implicit in the act of protest is the belief that a change will be forthcoming once the masters are aware of the protestor’s ‘grievance’. Only when that belief has faded and protestings end, will Black art begin.”

Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal edited the seminal book of the Black Arts Movement, Black Fire: An Anthology Afro-American Writing (Morrow, 1969). BAM was a natural progression from the Harlem Renaissance, in which there was a level of dependence upon white patronage.

The yet-to-be-named period where we witnessed another explosion of Black literary expression was heralded, in 1992, when three African American writers appeared, simultaneously, on the New York Times Bestseller List, Toni Morrison (Jazz), Terry McMillan (Waiting to Exhale), and Alice Walker (Possessing the Secret of Joy). This caught many observers by surprise, who were forced to reckon with the obvious conclusion that African Americans read, and that African American books can make money. These three writers would go on to achieve a level of prominence and wealth that escaped Black writers from earlier periods.

Alice Walker was instrumental in reviving popular interest in the work of Zora Neale Hurston, which renewed interesting in other writers from the Harlem Renaissance era. The popularity of those writers continues to cross generations. The demand for books by Harlem Renaissance writers is evident from the activity on AALBC.com. AALBC, the African American Literature Book Club, is the largest website dedicated to books by, or about, people of African descent and has been in operation for over 20 years.

Jean Toomer’s Cane was the very first book selected for our Bookclub’s reading list. J.A. Rogers (circa 1880 to 1966) is a 50-time bestselling author. Rogers’ history books and books on race, though published 100 years ago (his first in 1917), resonate with readers to this day. His top selling books on AALBC include 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro with Complete Proof, From “Superman” to Man, and The Five Negro Presidents. The books of many writers from the Harlem Renaissance have obtained bestseller status on AALBC including, The Ways of White Folks: Stories by Langston Hughes (1934), The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois (1903), and The New Negro: Voices of The Harlem Renaissance edited by Alain Locke. The popularly of these authors, on AALBC is quite remarkable, given that all of them passed away before the website launched in 1997.

Now, almost 100 years later, this stellar collection has been reissued as Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Its publication heralds today’s literary renaissance with the anti-racist movement sparked by the protests against police brutality after the world witnessed the murder of George Floyd. Over the weeks and months of global protests, many voices have emerged. America is finally waking up to what Black people have known since Obama was elected, that we are far from a post racial America. Perhaps the light in this darkness is that despite it, we are coming together, Black and white, men and women, to unite against racism and police brutality. Part of the unification is the awareness that it is not enough to not be racist, we must be anti-racist. We must actively oppose racism and promote the equality of Black and brown people. The new thought leaders in this literary movement span the spectrum from fiction, Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires; Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine by Emily Bernard; Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Water Dancer: A Novel; to nonfiction like Heavy by Kiese Laymon; Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me; Stamped From the Beginning and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi; Imani Perry’s Breathe: A Letter to My Sons, and So You Want to Talk about Race by Ijeoma Oluo. Continuing in the spirit of Sankofa, they, and so many others shine a light on the Black experience, and continue to inspire Black people, and the world to greatness.

Now, almost 100 years later, this stellar collection has been reissued as Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Its publication heralds today’s literary renaissance with the anti-racist movement sparked by the protests against police brutality after the world witnessed the murder of George Floyd. Over the weeks and months of global protests, many voices have emerged. America is finally waking up to what Black people have known since Obama was elected, that we are far from a post racial America. Perhaps the light in this darkness is that despite it, we are coming together, Black and white, men and women, to unite against racism and police brutality. Part of the unification is the awareness that it is not enough to not be racist, we must be anti-racist. We must actively oppose racism and promote the equality of Black and brown people. The new thought leaders in this literary movement span the spectrum from fiction, Heads of the Colored People by Nafissa Thompson-Spires; Black is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine by Emily Bernard; Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Water Dancer: A Novel; to nonfiction like Heavy by Kiese Laymon; Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me; Stamped From the Beginning and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi; Imani Perry’s Breathe: A Letter to My Sons, and So You Want to Talk about Race by Ijeoma Oluo. Continuing in the spirit of Sankofa, they, and so many others shine a light on the Black experience, and continue to inspire Black people, and the world to greatness.

Langston Hughes’ poem “Youth” is quoted by Locke in the book and it serves as a rallying cry and clarion call to greatness;

We have tomorrow

Bright before us

Like a flame.

Yesterday

A night-gone thing,

A sun-down name.

And dawn-today

Broad arch above the road we came.

We march!

Troy Johnson,

Founder, AALBC.com

September 2020

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston